4.15.24 — After Michelangelo After All

It was never easy to take in the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo himself labored beneath the ceiling on scaffolding of his own design, while struggling to reach the figures still taking shape overhead.

“Up Close: Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel” in 2017 brought thirty-four photographs to the World Trade Center PATH station—on their way to a second showing at the Garden State Plaza in New Jersey.  Maybe, just maybe, it brought with it a closer approach to the art. Still not close enough? Andrew Witkin lines a wall with images, so that there is no craning your head, but also no dispelling the mystery. On August 14, 1511, as the Sistine Chapel once again welcomed congregants to Mass, the ancestors of Jesus were conspicuously absent. So they are again with Witkin, just recently at Theodore through April 6, but you may think you see them in their silvery shadows, and I work this together with an earlier report on “Up Close” as a longer review and my latest upload.

Maybe, just maybe, it brought with it a closer approach to the art. Still not close enough? Andrew Witkin lines a wall with images, so that there is no craning your head, but also no dispelling the mystery. On August 14, 1511, as the Sistine Chapel once again welcomed congregants to Mass, the ancestors of Jesus were conspicuously absent. So they are again with Witkin, just recently at Theodore through April 6, but you may think you see them in their silvery shadows, and I work this together with an earlier report on “Up Close” as a longer review and my latest upload.

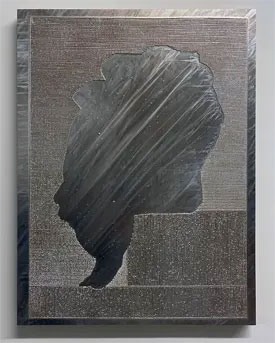

Even now, with so much else to see, visitors to the Sistine Chapel might never notice the ancestors. As Howard Hibbard notes, they are also among the hardest spots to see. They are missing once again today in etched magnesium. Witkin wanted to remove distractions, whether visual or in the ceiling’s details and history. Perhaps he hesitated to compete with Michelangelo as well. Yet their majesty and motion shine through in their absence—in the depicted stone on which they sat and in their silhouettes.

Michelangelo had kept a remarkable pace nearing the end of what is still the most celebrated project in western art—not just the scenes like the creation of Adam on the Sistine Ceiling, but also the prophets and nudes bridging the ceiling, the windows, and the walls. He had been laboring for five years, but more work lay ahead. He took down his scaffolding at last, so that Pope Julius could celebrate Mass and the Assumption of the Virgin. The rites completed, he set up lighter, more movable scaffolding to wrap up the lunettes, that awkward space above the windows. The familiar architectural element takes its name from their shape, like the crescent of the moon. Additional ancestors turn up elsewhere on the ceiling as well, with a lonely virtue prefiguring their absence.

Michelangelo had kept a remarkable pace nearing the end of what is still the most celebrated project in western art—not just the scenes like the creation of Adam on the Sistine Ceiling, but also the prophets and nudes bridging the ceiling, the windows, and the walls. He had been laboring for five years, but more work lay ahead. He took down his scaffolding at last, so that Pope Julius could celebrate Mass and the Assumption of the Virgin. The rites completed, he set up lighter, more movable scaffolding to wrap up the lunettes, that awkward space above the windows. The familiar architectural element takes its name from their shape, like the crescent of the moon. Additional ancestors turn up elsewhere on the ceiling as well, with a lonely virtue prefiguring their absence.

The ancestors may get passed over often as not, but Michelangelo did not lack for fame in his lifetime. His David alone assured that, as a standing nude and as a symbol of Florence’s independence. The ancestors, too, found a ready audience, in thirty-two prints from around the time of his death in 1564. Adamo Scultori, the printmaker, had the added cachet of working not from the frescoes one sees today but from drawings, by Michelangelo or a follower. I shall guess the former, given an artist who did not work well with others. He did fire his assistants, lock the doors, and start over with the Sistine Ceiling, with Raphael working and waiting just outside.

Still, you never know, for the drawings have not survived. In any case, Witkin’s plates are copies after copies—and they omit their very subject. The burnished metal surfaces in their place could be what Jacques Derrida lauded as marks of erasure. Andrew Witkin, also a dealer, must know well the postmodern vocabulary. He calls the show “After (After Ancestors).” So much for the originality of the avant-garde.

Got all that? Nor does he proceed as an engraver would, from the plates to prints on paper. Still, mind games may not be so bad after all, not in trying to pin down a long-dead, troubled artist’s mind. Besides, the metal shines. Scultori worked in dense parallel incisions, the cross-hatching of a trained draftsman—but not, as it happens, like Michelangelo drawings. Scultori’s technique may count as mechanical compared to his and already dated, but Witkin turns vice into virtue.

Make that competing virtues. With magnesium rather than an engraver’s copper, the shine ranges from dark gray to near white, while the visible cuts add to its energy and instability. And then come an uncut metal frame, its shadow on the wall, and the burnished omissions. Twenty-seven plates hang in three tight rows, unlike Michelangelo’s spandrels and lunettes. The unseen figures seem to struggle against the original curved framing, much like the originals. They call attention to Michelangelo’s musculature and motion in stillness.

Michelangelo did not play well with others either, and he may have counted the pope as his only male friend. Julius may increasingly have felt the same way. Hibbard, in his book on Michelangelo, attributes the languor of the ancestors, verging on sadness, to their role as precursors, neither here nor there. In 1511, though, as textbooks explain, the Vatican was losing its wars and bracing for an invasion. Dismiss the Sistine program as baggage, better off under erasure, but Michelangelo could not. One cannot separate its ambition from fears for what might survive.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.