Dinosaurs Walk the Earth

John Haberin New York City

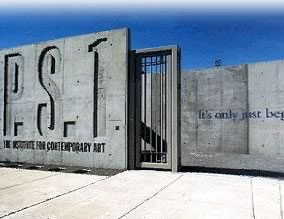

The Museum of Modern Art at P.S. 1

Is the modern museum a dinosaur? Maybe one flat on its back with a big grin.

The museum as lunch meat

Tom Merrick, for one, must think so. At P.S. 1 this winter, Merrick wedges his gigantic, bright green balloon dinosaur into the former schoolhouse. It fits the room as firmly and precariously as could Richard Serra's props of rusted steel. Kids who attended class here in the Queens museum building grew up long ago, but they would still get a laugh.  If not, at least the dinosaur smiles.

If not, at least the dinosaur smiles.

As my thoughts of Serra surely imply, a tight squeeze identifies art works with the museum. Serra used the device in his early years to hold his sheets of steel off the ground. They seemed ready to crash at any moment, and many viewers still find his work too threatening. Perhaps men look at the rod propping it up, ending at the wall as if sliced by the sheet, and think of something closer to home.

Yet Serra was toying with how Minimalism at its best works. By drawing the visitor into the room and the room into the work, he makes the museum and the viewer's experience part of the work of art. One is set free to embrace or to refuse art, the museum, and one's perception of the world. In more recent sculpture, Serra's sheets have grown larger and more comforting, in almost maternal curves. Yet they never descend to Minimalism as pretty icons. If they still scare people, the fears run deeper now, deep into childhood memories—and into the life of a late-twentieth-century museum.

I just had to think back to Serra that day in Queens. An early, much talked-about work of his always remains on view, a plain, metal channel, like a rectangular drainpipe. Cut into its rooftop chamber back when the "alternative museum" first opened, it might almost, I imagined, serve as plumbing. Like a literal drainpipe, it has metaphorically kept the institution from caving in with heavy weather since 1982.

Yet this winter P.S. 1 has caved in. A deal makes it an affiliate of the Museum of Modern Art's millennial monster. Like the Met into Central Park, the Whitney into Madison Avenue, the Frick online with virtual-reality simulation of each room, and the Guggenheim across Europe, the Modern has designs on Queens and a museum empire. Indeed, it is so comfortable with power that it exhibits art about about the museum, while the Whitney trumpets an American century.

Barely eighteen months ago, I hailed P.S. 1 as a true alternative, finer than any in Manhattan. In the early fall of 1997 it had just reopened after extensive renovation, and I felt so happy to find a vibrant re-conception of what an alternative space might mean. From a symbolically open courtyard entrance to its unisex toilets, from studio highlights to intelligent juxtapositions in special exhibitions, choices sprawled across every floor. Now I wondered at first if I had better not eat some crow—or should it be dinosaur meat?

Keeping the museum smiling

In no time P.S. 1 has become just another modernist dinosaur, another example of art up for sale—or has it? Has the Modern itself, as indeed conservative critics urge? Perhaps the Modern as postmodern museum has acquired a bright green, inflatable grin. I am not joking. The purchase reminds me why postmodernists toss around words like hegemony.

At the museum's main building off Fifth Avenue, or so one must call it now, the past century reins supreme. The architects plan another expansion, and Jackson Pollock's retrospective or Mark Rothko's shows once more why Modernism remains a vital part of any serious viewer's consciousness. Another exhibition, suitably oversized, features artists who take museums as their subject. They may well sound impressive, but hold off. The show quickly and effectively reabsorbs their critique into an existing structure. A postmodern contest of values cannot undo a modern museum, no more than can a modernist avant-garde.

Yet only a museum cannot absorb art—or another museum—without being changed, any more than I can. Yes, of course it can encompass the critical imagination, but then these acts become a part of it. Assumptions that one hopes to bury and to exclude will always underlie a conscious self-image. And so Pollock comes alive again, but not as a monument. His outsize ego, like an overgrown child's, begs the viewer and the museum to share in its vulnerability. Modernism's dream of rebellion somehow thrives on failure, the way Brancusi's totems have tumbled off their pedestal. That is what makes art today postmodern.

No wonder Merrick's work, if not exactly profound, had me thinking. From window to wall, it identifies the art museum with consumer culture's most enduringly popular extinct creature. Its title, Composition in Green and White, parodies museum priorities in another way, too. It brings "low" art directly into a museum, for it might as well have come from the marquee of a used-car lot. Conversely, low art lies dead, upside-down, and inside the traditional museum. No one can say for certain just who is grinning at whom.

I do not want to judge, even when it wipes the grin off my face. So do not lose hope, by any means. Critics have celebrated the opportunities of the museum merger. The Queens space can enrich its perspective by drawing on the Modern's permanent collection. If its director, Alanna Heiss, loves juxtapositions—what I had claimed a year ago makes visitors more aware of alternatives in art—now she can find a few new ones. She has already slated a collaboration with La Jolla's Museum of Contemporary Art, a much-needed retrospective of David Reed.

Meanwhile the Modern benefits from a provocative curator, contemporary artists virtually on call, and an open courtyard free of its legendary sculpture garden's constraints. Speaking of Richard Serra, I had been wondering what the Modern would do with massive Torqued Ellipses recently on display at New York City's Dia Arts Center before moving permanently to Dia in Beacon.

Pissing on the avant-garde

Nonetheless, I chilled to news of the museum purchase. Forget about how much room Serra's steel requires. Put it over the subway lines crossing out in Long Island City, and the street could easily collapse.

On a brutal winter Sunday I therefore grabbed the train to the outer boroughs while I still could. I wanted to escape the system oh that one last time, before MoMA uses the space for its permanent collection alone. Or at least I wanted to see if I could.

Things that seemed liberating before now have a scary double-edge. Take Mike Bidlo's bathroom wallpaper on the second floor. From ceiling to floor, Bidlo repeats an image of Marcel Duchamp's urinal. The grainy black-and-white photos recall the antiquity of early Modernism, as well as R. Mutt's black, scrawled signature.

Bidlo means to criticize how a museum incorporates, repeats, and numbs protests against it. By the playfulness of the theft, he revitalizes Duchamp after the Modern's institutionalization of tradition. In restoring Fountain to the bathroom, he metaphorically restores Duchamp's anti-art gesture, but with postmodern awareness of the ubiquitous museum.

However, Duchamp himself understood that no object forever remains anti-art. Today, one dignifies Dada as conceptual art, and Duchamp watched that retrospective transformation of his work without complaining. He saw no other response to the end of Dada and the birth of the modern museum, of Modernism as tradition.

Does Duchamp's acquiescence run deeper than the creative alternatives at the old P.S. 1? Or does this riddle pose alternatives within a postmodern awareness, displacing and invigorating the former choices between institutions? I no longer know, but I had to experience the layers of alternatives for myself.

The museum's encroaching darkness

Last year, P.S. 1 had every reason to take its pretensions seriously. With a fitting irony of history, its exhibitions throughout now run lighter in tone than at the amazing re-opening a year ago.

Back then, Marina Abramovic had turned the airy basement that into a scary, cavernous cell. Three ladders led only to unbearable ice, burning heat, and a knife-edged refusal of escape. Now the room holds Kcho's towering pile of boats and tires, about as profound as my childhood fights with inner tubes.

The rooms that John Coplans had filled with a brutal photographic record of his aging body now offer a career retrospective for Ronald Bladen. The black, plywood sculptures quite literally serve as hollow, light-weight portents of Minimalism. They work best at their most theatrical and outsize, and they come out of nowhere, after some tedious abstract painting from his early career. Bladen had a real enough influence, however, and the more ostentatious he gets, the more fun.

For the first time, an L-shaped work out in the courtyard looks like an overgrown toy shovel. Thanks to the show's thoughtful siting, it could almost be Pop Art before its time. Tony Smith's Die, the punning black cube in last year's show at the old Modern, must be growing jealous.

As at P.S. 1's reopening, Robert Wogan's tunnel vision of the museum corridor is still a high point, but the entire museum building, as ever, is a must see. Indeed, this time of year is perfect, if one can stand freezing cold, to catch James Turrell on permanent display. (Hint: Do not check your coat on the way in.) This room opens only the two hours before and after sunset, well after museum hours come warmer weather.

Turrell cuts a large square into the ceiling, giving blue, open air the illusion of a thick, ever-changing covering. The darkness and cold encroach like something palpable, no less than for Olafur Eliasson and his own cubes of light. If Minimalism puts space into the hands of a more active viewer, here one sinks into the work. I tried to pretend that the encroaching darkness did not make me think again of a certain midtown museum institution.

The museum beyond one's reach

All in all, though, my favorite work had to be the one that had me grinning the longest. Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, one of the institution's studio artists, invites one to enter a birdhouse. He carpets a room with thick grass, leaving a strip to each wall barely sufficient for visitors. Above the planters, wire hangers form a dense mobile, one hook simply resting on another's crossbar. A man has taken perhaps the object most associated with pre-feminist tragedy, and he makes it serve a comic spirit close to nature's wildness. No wonder I mistook his first name for a woman's, as in the Babar children's books, and I apologize for the misleading associations here.

The artist sets live birds free. They skip from perch to perch, setting the hangers in motion and turning it into sound sculpture with their own voices. They fly to the window overhead, just beyond one's reach. One feels oddly constrained to the walls, and yet that does not make the walls into the viewers' reserved area. One has the strange feeling of immersion in an environment while being foreign to it. Like the hangers stripped of clothing, one feels exposed without returning to nature.

As the birds fly off, art and the museum become a cultural layer that dismantles concepts of nature. (Her other art, too, takes over a gallery by soaring delightfully into the air.) So what of the museum's hegemony? It never vanishes, even as it dissolves into parody. I could be the docent for a parody museum. I thought of another act of museum imperialism, the Morgan Library's conversion of its upscale tea room into the restaurant Asia de Cuba. The West can still relive its staging of the Spanish-American War.

Heiss has gambled that museum empires literally mean museum proliferation. Anything can become the Modern, in effect, just as these days anything can enter the museum. I shall no doubt hear of a museum of museums next. If the gamble must fail, a postmodernist might well argue, it is also inevitable. Either art about the museum or a Pollock can equally enter the gamble, each a different way of recovering awareness of the risks.

Consumer culture, as in that echo of a used car lot, acts as a realm of pleasure and a place of forced desires. Modernism could never decide which is the greater truth. I still run scared, but I am glad that I caught the dinosaur's smile.

The final show for P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center as an independent institution—but hardly its last as a creative force—ran in the winter of 1999. With "Greater New York" in 2010, "Greater New York 2015," and "Greater New York 2021," the institution became MoMA PS1.