Baby, It's Cold Outside

John Haberin New York City

Anthony Dominguez, Raymond Saunders, and Mary Lovelace O'Neal

Official notice: you can become an outsider artist without ever venturing outside. Plenty of artists have, but not Anthony Dominguez on the cold streets of New York. Only now is he receiving a less chilly reception not so very far from where he once lived.

Raymond Saunders casts a long shadow. He cannot help it, not in a two-gallery show where the shadows will not stop coming, all but decimating the gallery walls. Its layers keep coming, too, in oil, graphite, enamel, oil pastel, and plenty of pasted paper. Unlike Anthony Dominguez, he is anything but an outsider, except perhaps to New York. Yet he, too, found his art waiting for him on the street. For him, that meant not its hidden corners and subterranean passages, but on boarded-up buildings and in the air—not too far after all from the wonders of bright lights in the big city for Mary Lovelace O'Neal.

Madness and civilization

Outsider artists have often been insiders in everything but their art. Many have worked diligently within a community, like the Gee's Bend quilters, and folk art in portraits has become an emblem of early American art. Yet a step outside the art world was never enough for Anthony Dominguez. He took to the streets for over twenty years until his death in 2014, and his art does nothing to disguise the costs. For him, even a cat begs to cat-sit for pay. Baby, it's cold outside.

Some outsider artists have been trapped inside with their madness, in an institution or in their head. And there is no getting away from the madness of his decision. Others artists have grown up in an artistic family, in his case with a commercial artist for a father, or dropped out after a few courses in art and headed for New York. Not everyone, though, abandoned an East Village apartment at the very depth of East Village malaise and the very peak of East Village art. Dominguez had to be ingenious just to survive, making art from whatever scraps he could find. Not surprisingly, he never made it to his mid-fifties.

Not that he cared all that much about the label outsider art, and he had one dealer and then another. Without them, his work itself could not have survived, although both galleries passed away as quickly as he. Yet he valued nothing so much as freedom, and nothing less than homelessness would do. One can see it in the show's very first work, where Lady Liberty in jail comforts a fellow prisoner. "What are you in for?" "Breathing."

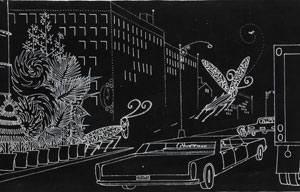

It is the closest Dominguez comes to hectoring. Uncle Sam and a cop with a dollar sign for a head parade right by, while others behind bars are either catching what sleep they can or dropping like flies. Once back on the street, though, his bitterness melts away. A comfortable jogger is just part of the pageantry, along with a man rich enough to toss a bill into one trash can, waste paper into another. In time, he found religion, but giant insects appear more often than a savior. Text within paintings accepts everything he saw, like one that gives the show its title, "Kindness Cruelty Continuum."

The gallery pairs it with a second show for writing found on the subways, in fake ads, doctored posters, and handwritten rants. Are they witty, tedious, or hateful? All of the above, and Kenneth Goldsmith, who collected them along with Harley Spiller, gives them a name from his poetry, "Are You Free on Saturday from 4–7 PM?" The words look suspiciously like an invitation to his opening, with tabs at bottom for your RSVP. Like Dominguez, Goldsmith would welcome anyone who can make it before 7. I just hate to think whether they would shut up.

Those scraps of raw prose underscore the sophistication of white on black for Dominguez. He brings totemic patterns to large works, in his paint's chalk-like line on black, and a delicate texture to decals pricked with bleach. He also brings color and the look of traditional samplers to songs after teaching himself to write music. Even the street scenes stop short of cartoons, although one might as well call them a graphic novel. Yet he would still rather be alone. As one lyric begins, "Company loves misery."

Casting a shadow

For Raymond Saunders the details accumulate, in years of found objects, frail scraps, and paint—to the point that one can neither put a name on the shadows nor dismiss them. They may lurk in the background, as shadows in the shadows, or seemingly leap right off the canvas, aiming for you. Should you start in Tribeca, a shadowy figure does both just as you come in. You may find yourself poring over the clues, there and in Chelsea, to see where they lead. If you never do find out, try not to blame yourself. That first shadow is watching.

Black may be his favorite color, but it is not his only color. That figure's bright yellow face and shock of hair would be hard to overlook even if the rest of his body were not hunched within a loose black coat. But then the yellow continues unbroken behind him—and the blackness returns behind that. Saunders loves reversing expectations, including the expectation that the ground must be white. He must like, too, undermining the distinction between painted image and ground. Works hang on the wall and serve as walls themselves.

Black may be his favorite color, but it is not his only color. That figure's bright yellow face and shock of hair would be hard to overlook even if the rest of his body were not hunched within a loose black coat. But then the yellow continues unbroken behind him—and the blackness returns behind that. Saunders loves reversing expectations, including the expectation that the ground must be white. He must like, too, undermining the distinction between painted image and ground. Works hang on the wall and serve as walls themselves.

Black functions as a ground for fields of color, like that yellow or a tart reddish pink. It may serve, too, as a playground for his impulses, in chalk scrawl. Numbers in that shadowy first painting run horizontally, as if to count the seconds, while a tribute to Charlie Parker reads Bird above a poignantly small photo. Approaching ninety, Saunders is old enough to remember when chalkboards, meaning blackboards, were black. Above all, a painted surface may serve for whatever he cares to find, whether advertisements or warnings. He calls the show "Post No Bills," after a 1968 painting and the image it contains, but then he has no qualms about breaking the rules, including his own.

The show has more room to run through his violations in Chelsea. His methods suggest graffiti, but he is defacing only himself. It returns him to the streets, and his quotations are decidedly urban. Like black, they also allude to his status as an African American. While the LA artist has had little exposure in New York, he is at home enough to borrow a delightfully nasty front page from the city's once-stellar alternatively weekly, The Village Voice. You may have forgotten whatever scandal, but he has not.

The references can be inscrutable, especially compared to the text art and political art of his time. You may dismiss his collage on one visit as a waste of good waste, see it on another as dazzling. (I did the first on catching him in LA art at MoMA PS1 in 2013, and look now.) Still, he will always have a firm reference point in the shadows and himself. An artist's palette is just an illusion, but brushes are real enough, as if painting themselves. They are also black.

His favorite or not, "Black Is a Color," as his 1967 manifesto has it. I can only wish that a formalist like Ad Reinhardt had adopted it as a motto, but Reinhardt died two years before. Like a Minimalist himself, Saunders works monochrome and the space as well. He covers some walls in his tar-like black. He cloaks others in a caked white that is already coming off the wall. Naturally the cracks are black.

Bright lights, black city

Mary Lovelace O'Neal left her teaching job at Berkeley in 2006, for a studio in Mexico. It would not be my choice, but she can stand the heat. She can always retreat in her imagination to New York at midnight, when the sky is black and everything is cool. Black for her is definitely a color, and it animates some lively figures darting across the night as well. Just to speak of it as her ground belies how light they are on their feet. It embodies her own blackness as well.

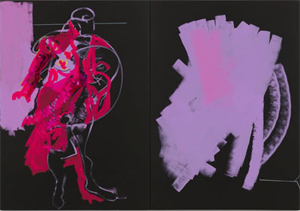

Her latest includes Round Midnight, after Thelonius Monk in jazz, and Bright Lights Big City—and do not so much as think of the once fashionable novel of that name, about white hipsters in the 1980s taking big money to Tribeca nights. This is the big city of the blues and of rolling in my baby's arms. It is the city of Manhattan and of Rooftops Where Women and Cats Rule. Even in her eighties, that means her. Yet her show is "HECHO EN MEXICO—a mano," or made in Mexico by hand, and her hand has never been more visible. It helps that she starts with black and that her acrylic looks a lot like drawing.

Lovelace O'Neal started to apply lampblack as a student at Colombia, with a blackboard eraser. Even then, she was changing the rules. That kind of black is left over from burning, but now it became a place to begin, and an eraser was laying down rather than cleaning up. Echoes of the blackboard appear again with white curves that look like chalk. They can stand for anything from shoelaces to long hair, although they may look like graffiti or accidents. Like graffiti, too, they can produce text now and then, like a tag—this time out, for Little Black Sambo's Green Coat.

She can be more consistently colorful and painterly, as with her whales, featured in the 2024 Whitney Biennial (and a concurrent show runs at SF MOMA). That and her mural scale make her an heir to postwar abstraction. Here, though, that leaves plenty of space for black. The show has just eight works, but they run up to four panels across. As with Saunders, black sets off layers of bright color, which then acquire more black as figures in action. They can be human, animal, or both at once, charming enough for cartoons, but do not dare call them cute.

She is as hard to pin down as her location. Born in the South, she refused to become a southern artist, and after Colombia she left for the West Coast. She had a residency in Morocco, a term with a print collective in Chile, and a stop back in New York for a print studio run by Robert Motherwell. Like Kara Walker, Lovelace O'Neal trades in African American stereotypes, only to take them apart. Little Black Sambo, now with a woman's braids or tresses, lies on her black, weighed down by that green vest. It might be the heavy kind used as protection from x-rays. She might be doing everything she can to remain on the margins, and she has shown only rarely in New York, or she may simply identify with black artists as outsiders.

How she keeps New York in mind is beyond me, but it helps that she also keeps her edge. The jagged edge of color brings an edge, too, to the black ground. If color becomes a figure or a layer of pure painting, fine. That cat-woman faces down a purple cat that could be anything at all. Her featureless black face could belong to anyone or any gender as well. She has her stylish clothing or body armor in bright red—and a wound of red on yellow across from her absent heart.

Anthony Dominguez ran at Andrew Edlin through April 6, 2024, Raymond Saunders at Andrew Kreps through March 30 and at David Zwirner through April 6, and Mary Lovelace O'Neal at Marianne Boesky through May 4.