A Show of Erudition

John Haberin New York City

The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library

Hunters Point Community Library

Not everyone can have a library like J. P. Morgan's, but one can always have the shelves. At least one can with enough money. Those with a spacious enough interior can put on a display of erudition, if only for show.

I cannot swear that the fashion ever really caught on, but it had its moments. It presents an impressive appearance, of fine bindings, but as little more than wallpaper. What look like shelves have no books at all, and they roll back to reveal the room's true function apart from the display—as closet space and a private study.  Wish you, too, had a mansion to spare or a sufficiently dowdy building? How about the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library? You might be just as impressed, up to a point, and just as disappointed.

Wish you, too, had a mansion to spare or a sufficiently dowdy building? How about the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library? You might be just as impressed, up to a point, and just as disappointed.

Stavros Niarchos serves as the central lending branch of the New York Public Library—a treasured counterpart to the landmark research library by Carrère and Hastings, diagonally across Fifth Avenue. Yet its renovation has less to do with reading materials than with barely accessible shelves and wasted space. Not that other libraries are above pomp and circumstance, as some of the city's most valued public spaces. New and improved libraries at Hunters Point and elsewhere put on quite a show, too, while accommodating the many with needs other than books. A comparison, though, suggests what their display gets right. The digital age and atria need not mean a library without books.

Library sale

New Yorkers have been waiting for this. The former Mid-Manhattan Library closed in 2017 for renovation, and there was nothing like it, with space for more scholarly volumes than local branches can hold. The closest the system came before it was the Donnell Library, across the street from the Museum of Modern Art. And it closed, too, shortly before, returning as the 53rd Street branch, with more modest expectations. The pandemic delayed full opening of Stavros Niarchos until July 2021. Art and architecture after Covid-19 will never look the same.

The extended closure could only drive home what one missed. During construction, one could reach many of its resources, but only through a dingy side entrance to the research library on 42nd Street. Others remained in storage, available (eventually) on request. Like other branches, the new library opened tentatively for a while for "pick up and go," subject to the vagaries of books on hold. One could just as well pick them up somewhere closer to home at that. Or one could just stay home.

The opening felt a part of the return to life of an entire city. Besides, renovation was welcome, because the Mid-Manhattan Library was a bust all along. It took over from a long-forgotten department store. Arnold, Constable & Company dated to 1915, but it left behind the blank face of modern architecture on the cheap. The bland interior, too, became a lesson in what not to do. An escalator, for example, held out the temptations of easy access, but it ended on the second floor, leaving you to wonder why you had bothered with it at all.

The library's solution? Shut the whole darned thing. It planned to sell the site, moving books to the research library. If that meant consigning others to storage, who needs books anyway in this day and age? To rub it in, Norman Foster, the British architect, proposed to sacrifice still more space to an atrium. Public spaces matter a great deal to the new Moynihan Train Hall at Penn Station, but the research library's reading room is spectacular enough on its own.

The system's president, Anthony W. Marx, still defends that plan, but the public was not buying. Ada Louise Huxtable of The New York Times spoke in defense of architecture and many more in defense of research needs. What, too, of the hypocrisy of reducing space and cutting costs in the name of expansion? Money talks, and the real motive have come down to income from the planned sale. Even now, the library has sold off its branch for science and business in another former department store, a more luxuriant one, B. Altman. Stavros Niarchos will just have to make up the difference.

Money still talks, as with the name change, to honor a generous donor. The central research library was already renamed for Stephen A. Schwarzman, but you will pardon me if I always call it the lion library, after the stone lions flanking its grand entrance. Local libraries (apart from Donnell, after a nineteenth-century cotton merchant) are named mostly for their location—although my earliest library memories are of the Saint Agnes branch on the Upper West Side. I trust that Saint Agnes was not a donor. Money, though, cannot be the whole story. There is also a concern less for books and users than for appearances.

So much for books

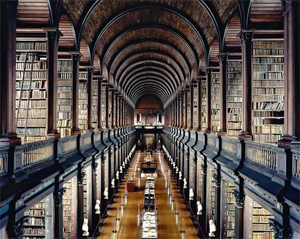

Appearances do matter, and Stavros Niarchos has a few to die for. The architects could do nothing about the exterior, and funding for that would have helped, but step inside. A checkout counter and light-wood desks, for library staffers that never seem to appear, dominate the entrance floor, along with a wood drop ceiling (and the escalators have gone).  Off the elevators on the second floor, a large photo by Candida Höfer shows an older library in uncanny high resolution, with stacked shelves flanking a high ceiling. It is not the majestic research library across the street, but Trinity Library in Dublin. Could Francine Houben of Mecanoo, a Dutch firm, and Elizabeth Leber of Beyer Blinder Belle have taken something like it as a model?

Off the elevators on the second floor, a large photo by Candida Höfer shows an older library in uncanny high resolution, with stacked shelves flanking a high ceiling. It is not the majestic research library across the street, but Trinity Library in Dublin. Could Francine Houben of Mecanoo, a Dutch firm, and Elizabeth Leber of Beyer Blinder Belle have taken something like it as a model?

Far to the right, along the library's east wall, five levels of shelves span three floors. One can see them at a glance, because the second- and third-floor ceilings give way just before them, for the sense of a larger and more open architecture. A ceiling painting by Hayal Pozanti on the fourth floor enhances the visual unity. Its hard edges, bright colors, and whimsical shapes recall the ambitions of public art under the New Deal, like the WPA murals at the Brooklyn Museum. The shelves, though, are the true capstone. They look back further, to the great libraries of the past, while promising that the books you want are, at last, available now.

They are not, though, available without effort. One must find the door to the stacks—and then, for two of five, stairs or an elevator to a mezzanine. That means a second flight of stairs or elevator, apart from the central ones starting on the ground floor, with the "local" elevator in a remote corner at that, safely out of sight. Worse still, the books for which you hoped may not be available at all. Much of each floor is largely empty of them or, for that matter, anything else beyond a row of computers. The few remaining shelves, where the shelves of the Mid-Manhattan Library once stood, have shrunk to the height of a child.

Is this, then a mere display of erudition and outreach with none of the real thing? Could the architects just as well have put up wallpaper shelves, leaving the books where they were? Even the display is something of a token. The narrow gap in floors and ceilings is no big deal. On my first two visits, navigating the endless tables, I did not even think of looking up and missed the abstract painting. Still, the semblance of a skylit court has taken priority over the collection.

It is not alone. Museums everywhere have made an atrium their priority, like the awkward one at the expanded Museum of Modern Art—where a clever installation by Amanda Williams makes it an emblem of museum dysfunction. Much of the Morgan Library has become a coffee shop since its Renzo Piano expansion. The atrium serves as a useful bridge between exhibitions and meeting or office space to the north, where Morgan himself lived. Still, it makes Morgan's personal library a detour that few are likely to take. Thankfully, the museum's commitment to drawing, illuminated manuscripts, fine bindings, and book art remains.

Without question, public spaces like these serve a purpose, like the new hall at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Museums are places to gather, and libraries are a refuge. Digital collections are growing, and not everyone has computer access at work or at home. Upper floors at Stavros Niarchos add a much-needed business center and learning center, while the ground floor adds space for children to read, relax, and explore. Who am I to object if it also adds a terrace, with a café and views of Bryant Park? Still, something has gotten out of hand.

Real libraries and token images

How far out of hand? It may help to look at other library renovations in just the last five years. The 53rd Street branch, opened in 2016, centers around a staircase, with broad, thick tiers suitable for seating. They take up a ton of space, and one must descend past them to use the library, but they make an impression and draw a crowd. More recently, Toshiko Mori has redone the interior of the Brooklyn Library's main branch on Grand Army Plaza, with an eye to brightening up. I may prefer the old exterior to anything inside, especially during the Saturday farmer's market, but the changes serve a clear purpose, both practically and visually.

A greater drama, though, unfolds in Queens. Its libraries have never had much of a reputation for their contents. Still, like Brooklyn, the borough has its own system, and that has given it the freedom to think outside the corporate box. Elmhurst Marpillero architects have added glass boxes to either side of the Elmhurst branch—and not just for their own sake. They create an overall unity that transforms the original building as well. By far the coolest branch, though, opened before the pandemic, after a decade of construction, facing the actual gantry in Gantry State Park across the river from midtown.

Steven Holl's Hunters Point Community Library is only the latest addition to Long Island City—but also the furthest from its cookie-cutter condos, and it has already found emulators in "Architecture Now" at MoMA. A healthy chunk cut out of the top can make anyone forget that one has come upon a five-story white slab.  So, up close, can texturing of the slab, with a multitude or razor cuts in its silvered concrete. So must of all can the cut's echoes in large windows twisting and turning every which way—with one more nestled improbably into a corner of the base. From the inside, they offer views of the waterfront park, the United Nations, and Louis Kahn's Four Freedoms Park on Roosevelt Island. From the inside, too, the neighborhood's monstrous but long-overdue gentrification does not look half bad.

So, up close, can texturing of the slab, with a multitude or razor cuts in its silvered concrete. So must of all can the cut's echoes in large windows twisting and turning every which way—with one more nestled improbably into a corner of the base. From the inside, they offer views of the waterfront park, the United Nations, and Louis Kahn's Four Freedoms Park on Roosevelt Island. From the inside, too, the neighborhood's monstrous but long-overdue gentrification does not look half bad.

Like it or not, it is a community library for a burgeoning upscale community, with magazines and newspapers to one side of its second floor and space for kids on the other. If books further upstairs seem an afterthought, getting there is half the fun. Stairs, ramps, and a curved wood ceiling to one floor break up the interior. They present quite a puzzle at that, but I look forward to getting to know it. It is still not much of a library when it comes to its collection, and any one floor offers little more than an alcove to either side. I did, though, find a late play by Shakespeare that had eluded me at Stavros Niarchos an hour before.

The allure of the atrium lingers, whether the supposedly public space is used or not. Neither 53rd Street nor Hunters Point has the least use for its ground level. Elmhurst's glass houses are at their most glorious lit from within at dusk, when the library is closed. Still, they have reasons for what they do, they are up front about it, and it alters their vision of the site as a whole. And that is just where Stavros Niarchos falls short. If it has a vision at all, it is a depressing view of the future.

Form may not follow function nor function form, but each has a say. Middle floors have their form, the stacks, while floors with an obvious function, the business and learning center, do have a point. If the stacks are no more than a show, the librarians are nothing if not practical. They consign liberal arts like literature to the mezzanines, so that business, computer and law books come first. Yet there, too, they leave the very idea of a library behind. Readers will just have to settle for a token image of the present and the past.

I did not visit any of these libraries until July 2021.