Bad Art and Human Evil

John Haberin New York City

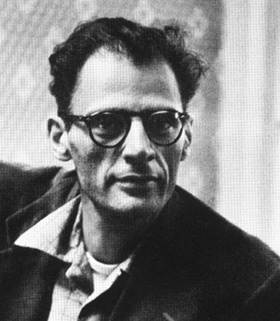

Arthur Miller: The Crucible

One hears far too often about "shock art" and "bad art." The Royal Academy lets in dead cows and reminders of murder, along with the rest of the trendy Brit pack. After three decades, Lolita has enough shocks left that all distributors disdain a film of it. In commercial terms, the artist has once again become an exile.

After a century of Modernism, then, artists presumably still thumb their nose at fine art and moral values. I should know: my hands are all thumbs. And, of course, everyone gets to feel duly alarmed, disgusted, or liberated.

The problem is knowing whether there is any distinction left between good and bad. The more electric the shocks, and the more strident the shocked, the more they seem to be fighting in vain against history. It might help to try a different kind of nostalgia. I want to look back for just a moment at the art that turned its back on good and evil.

Arthur Miller's The Crucible is about an adulterer and the rejected lover who gives birth to a witch hunt, but this essay of mine is not about President Clinton. Once again, cries of witchery may be greatly exaggerated. It is about how art forces people to judge—and to fear their own best judgment. It is about why I wish that, in culture as in politics, the media could stop looking to Hollywood for its plots.

Bewitched

A witch hunt separates good from evil, on bogus grounds. It makes people of courage cry out to reverse the terms: oh, no, the witch hunt is the real evil. The supposed evil characters are not bad people at all. They are victims, and they may well become the conscience of the community. Responses like those were natural ones in the McCarthy era. For some, they are essential now for politics, when the first president to defend sexual-harassment laws is, perhaps, being railroaded.

I find Miller even more courageous, for he wrote in far more frightening times, and yet he only seems to take that route. The play, I think, is about replacing the terms good and evil with a nuanced understanding of good and bad. That is indeed the ultimate lesson of a witch hunt, when the greatest evil is what good men and women tolerate and what they can face about themselves. That is also what makes The Crucible a magnificent play in an era that discouraged magnificence.

John, the hero, has cheated on his wife—with a minor! (Hey, this is only two years before the outcry over Lolita.) And he knows it, too, knows it enough to be shamed by it and to admit it to others when that admission risks his life. He cries out for the truth, when the truth is more than he within can bear.

His wife is reserved and rigid. I bet that a poor marriage counselor would tell her that she drove her husband to stray, and she may well come to feel that for herself. Yet she loves him, and she sticks by him when it counts.

Abigail, the girl he loved, suffered first seduction and then rejection from an adult, but out of it she forges hatred and a social catastrophe. The other girls accused of witchcraft go along, and how much is sheer cowardice, fancy, fashion, and foolishness? How much rather is blistering peer pressure or an all-too-merited fear of the authorities, fear even of death? How much is plain hysteria, something past conscious control? Psychologists today prefer to speak of a "conversion disorder," which may have "modeling," or imitation, as its trigger and formative influence. They may take the Salem trials as an (apparently) easy example.

The inquisitor stands for virtue but kills. Is he blinded by his ideology, focused hatred, or fear of what he cannot see? The community begs for virtue, but it follows with a cowardice that makes virtue all but vanish forever.

Spinning Lies

Miller asks one to compare all these. His audience must grasp repeatedly for nuances that one may never understand. How does a community's acquiescence differ from following Abigail? How does John's hypocrisy compare to the hypocrisy of his inquisitors? What led to any one of these? Is it meaningful—no, essential—to speak of "more sinned against than sinning," or is that still another coward's lie? What is art if no man or woman can spin lies?

The Crucible is a "social" play, "political" art, but Arthur Miller is the same playwright who created the lyricism of A View from the Bridge and the imaginative, confessional dream that haunted him After the Fall. The set for his Death of a Salesman reduced the harsh postwar social reality to an "unrealistic" wire frame.

The 1950s tossed off some deliriously "bad art"—with Rauschenberg in his combines and Warhol, in fact, intentionally and brilliantly. The Crucible is bad art in quite another sense: it dares to embrace the bad because the alternative is to imagine evils. In the process it offered fervent prose, people, their reality, and moral sensitivity to a desiccated theater. In the silliest as well as the harshest of times, I guess I do need bad art. Shock art comes only when bad art has lost its vitality.