Opening the Artist's Book

John Haberin New York City

Content Through Structure: A Panel on Book Art

I spoke something like this in a 2021 panel on book art sponsored by Central Booking. It was one of several panels in the 2001 Center for Book Arts Contemporary Artists' Book Conference. I return later to its title, "Content Through Structure: The Critical Focus on the Artist's Book as Object." Other speakers were Pablo Helguera, Maddy Rosenberg (who organized and introduced the event), Miriam Schaer, and Mary Ting.

Thank you, Maddy, and thank you, everyone, for coming. I promised to speak about what I expect from myself as a critic and what drew me to the artist's book, and I hope to convince you that they come down to pretty much the same thing.

Now, my opening image is only a placeholder while I get going, but it was just too beautiful to pass up. It is from The Hours of Henry VIII, a book of hours by Jean Poyer from around 1500, but while I'm here, let me ask you something. What place is there for an artist's book in art history—or by extension in art now? You will not find it in a textbook, and artists across Italy did not flock to see it as they did to The Last Supper in Milan. They could not have, for it was between the pages of a book in France. And yet, at the very height of the Renaissance, book art was offering something more intimate and personal, with a greater naturalism and, simultaneously, the sheer fancy of a summer idyl.

A natural interest?

First, though, a bit about me. I might seem a natural audience for book art. I was a bookish kid long before I took an interest in art, and I have been both an arts writer and a textbook editor for years now. Then, too, my education is in physics, and my most successful and rewarding textbooks have been in chemistry, so I had to feel a shared interest when Maddy Rosenberg and Central Booking devoted a space to exhibitions about art and science. You may have noted that Maddy named it HaberSpace. Frankly, I think it's an awful name, but I'm honored all the same, and I shall draw for examples where I can on my past reviews of shows there.

That space is gone for now. But I still had to love just last month stumbling on Melvin Way at Andrew Edlin gallery. Way, an outsider artist at a gallery dedicated to outsider art, treats his own handwritten and only slightly outrageous chemical formulas as a scrapbook or a journal, a kind of book art, and the results are somewhere between hypnotic and laugh out loud. But even more, I feel an affinity with any artist who combines words and images, because that is what critics do. At least it is what critics should do. Let me explain why—and why so many let me down.

If you asked people what makes a good critic, you might hear good taste. Pressed a little further, they might add that art can never be put in words, and words (all that nasty "theory") might even be an obstacle to looking at art. I think that's wrong on both counts. I am not here to pick winners and to plan your weekend, and you are welcome to think that I have just dreadful taste. Rather, the art historians and critics I have most admired use words as an entryway to experiences that I would otherwise have missed, and I want to do the same for you. I would be truly flattered if you read something of mine and found that it challenges your tastes, too—or thought, hey, John doesn't like this at all, but now I'm intrigued, and I just have to see it.

Many people love contemporary art but find art history remote, stuffy, or mysterious, not to mention really expensive. And many people, like my own parents, look at contemporary art and wonder why it's art at all. But even the best of us can benefit from new perspectives. And critics can help by telling stories about a work of art—providing context and suggesting how to look and where to begin. That is why I started a Web site twenty-five years ago, haberarts.com, to be free of the limits of most art magazines, with their refusal of time and space to think, and it has grown now to have covered thousands of artists past and present. Come to think about it, what does art itself do if not open you to new experiences—of other places, other times, other ideas, and other people? We call that diversity now, and we value it, but it has been the secret of art all along, including book art.

All that said, I was slow in coming to the artist's book. Why? For one thing, it seemed only right to keep my interests separate, as they deserve to be. Art, books, and, yes, science are too important to serve as mere metaphors for one another, rather than disciplines with a sense of rigor and a sense of wonder all their own. If I hear one more time that Einstein's relativity means that everything's relative and quantum mechanics that life is uncertain, I'll scream. The beauty, in fact, of a good artist's book is that it does not take art or books lightly.

For another thing, book art for me was just plain under the radar, like my opening slide, as I'm afraid it is for many others as well. Surely that is why Central Booking exists—to fill a need. If you have attended Art on Paper, the art fair, you will have seen almost no book art at all. Nope, just posters and prints, although this hideous photo from the fair's home page suggests otherwise. And one reason is that books run up against a common assumption about art. I vaue art in a more public arena myself.

Inside the object

Maybe you, too, frequent public spaces like big galleries and museums. And maybe you, too, have hunted down the Holy Roman Empire and the birth of the Renaissance in churches and chapels across Italy, like this from Giotto at the Arena Chapel in Padua. A public scale also drives Abstract Expressionism, earthworks, and more of my favorite art. That can make book art easy to overlook. What, then, finally won me over? To answer, we have to ask what book art is all about.

What opened my eyes was the range of valid answers. On the one hand, an artist's book is an art object, like a canvas or a sculpture. The title of this panel insists on that. On the other hand, it is the contents of the object, its words and images, or the very process of publishing a book. The next panels in this conference, in turn, are about just that. But book art is all of these and more, from the conventional illustrated book to unconventional combinations.

Take a show right now at the Morgan Library, about Claude de Laubespine, a patron of the arts in Renaissance France. It's in that tiny gallery off the Morgan's lobby, which you might easily rush past on the way to the big stuff. Please don't. Here a bound book is, yes, a magnificent object, by an artisan or artisans known only as the Mathieu Aesop workshop (because it also created the binding for an edition of Aesop's fables commissioned by a gentleman named Thomas Mathieu). But open the book, and you can find equally intricate words and images by France's greatest poet and artisans. On top of that, each book was a step in building a library, as a work of architecture and intellectual history.

So that brings me back to book art now and Central Booking. Over the years, it has featured images, like this invocation of her personal fossil record from Mary Frank. She is just one example of an older woman artist finally getting her due.

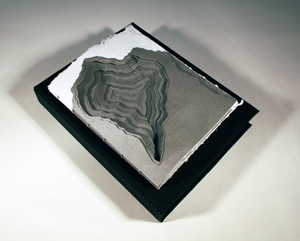

Yet book art here also means the sculptural object, as when Michelle Wilson uses ladyered cuts to transform a book into an endangered landscape, after Bolivia.

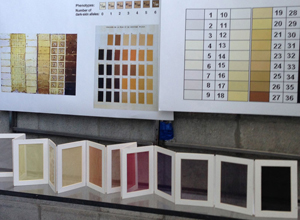

Or here Geraldine Ondrizek adapts the tradition of an accordion book to information science, as Shades of White. They assert themselves that much more as art objects in that you dare not turn the pages.Other works from past exhibitions at Central Booking are harder to place, and that, too, is part of the range of book art. Paul Tecklenberg called this Dark Field Cluster. It is a seeming microscopic view but on a human scale, adding to the ambiguity. I shall not say how he made it. It falls on which side of the equation—image, object, or image of living objects? The strength of the artist's book is that I can leave the answer to you.

To return to what turned me off in the first place, I have since gained a new appreciation for what goes beyond the public face of art. When I reviewed a show of illuminated manuscripts from early Renaissance Florence at the Morgan Library, I began with a question. What if the real Renaissance took place in secret, and what if centuries of Western art were born in miniature? Now, sure, there is another private side to art—in illustrations for poetry or in sketches as studies for future paintings or for the artist's closest friends alone. A book, though, exists for all to see, only just one person at a time. Opening the artist's book can be an eye-opener.

"Content Through Structure" took place on Zoom on February 27, 2021.