The Gallery as Relic

John Haberin New York City

Gonzalo Fonseca and Isamu Noguchi

Nancy Graves and Fossil Tales

Is fine art a relic of a less cynical age, and what about Modernism—or the gallery? Gonzalo Fonseca builds on Isamu Noguchi, even as he appears to excavate lost civilizations.

Fonseca might have felt himself something of a relic. He knew well modern sculpture, and it fed his work, as did the dreams and anxiety of Surrealism. Yet he survived to experience Minimalism and beyond, and they, too, touch on his art. Another artist known for relics often sticks to skin and bones. Yet Nancy Graves could also allow her imagination and rocket science alike to take flight.  Closer to the action downtown and perhaps a premature victim of it as well, "Fossil Tales" refuses to see artist books as extinct.

Closer to the action downtown and perhaps a premature victim of it as well, "Fossil Tales" refuses to see artist books as extinct.

Sculpture as site

Gonzalo Fonseca treats sculpture not as an object only, but as a site also. Vertical slabs break for windows, niches, and doors like houses, churches, or public buildings. Tabletops display the ruins of entire cities, if not entire civilizations. Works on paper sometimes read as maps. One can hope to piece out their components, in towers and arenas. One can hope, too, to imagine what remains hidden and what has been lost.

Of course, they also have a site, at the Isamu Noguchi Museum, and Fonseca could count on Isamu Noguchi as a mentor and a friend. Born in 1922, in Uruguay, he was more than thirteen years the younger of the two, but the show brings them closer together than ever. Both lived and worked in New York while traveling overseas—in Fonseca's case to Italy, where he died in 1997. There he sought the marble for his largest work. A few examples, in an entrance hall, frame a visit to both artists. A retrospective continues upstairs, and one could mistake much of it for one by Isamu Noguchi himself.

They share their materials, in marble and stone—whether finely polished or coarse, fragmented, and raw. They share Modernism's formal language with something more allusive and harder to pin down. They share, too, the duality of horizontal surfaces and rising verticals, with the pedestal a more than equal partner in the work. When I spoke of a tabletop, I should have said a table. Fonseca still creates objects after all. He is also, as Noguchi is not, obsessed with representation.

He could well be in search of a site—and only partly because his points of reference lie in ruins. They lay bare staircases and entryways, as points on the way to somewhere else. The windows could stand for windows onto the soul. Other imagery includes ladders and eggs, presumably unhatched. Horizontal planes and bulky supports also run to the deck and hulls of ships, with destination unknown. The sense of time already past lies over everything, often as not as madness. One head, to judge by the title, belongs to the emperor Nero.

Fonseca's reputation, too, needs some excavation. Modernism, not least that of Noguchi, just does not have much time for the trappings of profundity. Still, maybe neither at heart does Fonseca. Ancient Rome for him had its theaters, but only as show. Imagery runs to fingers in a box and to enlarged feet, but at least partly as farce. They could be less serious than they appear.

His roots lie in painting, which may explain the maroon that occasionally competes with the white marble and battered gray of limestone. And painting here means Surrealism. A pendulum, one of his favorite devices, may suggest a site's transience, ticking off the moments, but also a full moon. The repeated cavities also suggest an empty house. Ink often adds a finishing touch, to spell out the supposed subject matter. Remember, though, that fingers might create and feet might support a sculpture.

To the moon and back

Nancy Graves devoted so much of her work to skin and bones that one can almost forget how much it was alive. She had her eye so close to the earth, too, that one can forget how much it took flight. Not that she failed to look behind her then to the landscape that she knew so well. A notably low-tech artist found inspiration in NASA imagery of this planet. They led her back to painting, but without losing the scale and physical presence of her sculpture. An exhibition on the fiftieth anniversary of the moon landing shows her "Mapping."

A trip to the moon and back demanded clinical precision, but a leap of the imagination as well, and Graves in the early 1970s aspired to both. A work on paper, ostensibly untitled and assigned a number, bears the parenthetic subtitle Drawing of the Moon. And its dense specks of watercolor, gouache, and pencil may well replicate the moon's craters, but it also recalls a famous shot of the earth as a habitable world from high above. That image helped people to see planet earth as just one more body in a larger universe, although a precious one that it would be a real shame to spoil.  (Climate change deniers take note.) As a work on paper, it may look mostly abstract and cheerful, but the show quickly finds a reference point.

(Climate change deniers take note.) As a work on paper, it may look mostly abstract and cheerful, but the show quickly finds a reference point.

With a little help, one can see past the pixels in the drawing next to it (at least I think so), to the base camp and lunar module. Even without help, though, paintings look like satellite imagery, and their specks and pixels look like tools of the trade. That includes the scientist's trade, in weather maps and photographs in other than visible light. It also includes the artist's trade, from a time of rule-based procedures and Minimalism. Graves studied at Yale with Jack Tworkov, the Abstract Expressionist, but his students had other things in mind. That could mean a sparer abstraction for Brice Marden and Robert Mangold, the wilder patterning of Jennifer Bartlett, or a very different kind of pixilation and precision in the photorealism of Chuck Close.

Graves had touches of all those, but they may not immediately spring to mind. Neither, for that matter, may digital technology—for an artist who, like Robert Rauschenberg, also collaborated with dance. To the extent that she merges art and science, like Remy Jungerman, it usually means anthropology or archaeology. She had her best-known work with Camels in 1969 and Out of Fossils 1970. The camels look heavy, hairy, parched, and dry, and their materials, including animal skins, also hung as independent sculpture. The fossils are bone fragments of steel, wax, and marble dust, and Graves was still pursuing fragments and fossils some twenty years later in bronze. She died of cancer in 1995, at age fifty-four.

The sculpture shares a creepy poetry with such artists as Eva Hesse, Kiki Smith, Alina Szapocznikow, and Magdalena Abakanowicz—and she briefly married another artist with imposing masses, Richard Serra. Graves takes more seriously, though, concrete images of life and death. Those images disappear entirely in her mappings, but along with the creeps. Still, she is again looking to a specific place and time for the conditions of life. She has appeared in a show on the theme of "After Nature," so it only makes sense to turn to NASA for a look after and a look back. The choices, though, do not just render photographs in paint.

These are large works, up to twenty-four feet long, in mostly black and white—although the science supplies some harsh, vivid color. The longest covers four panels, while another covers slim staggered panels at an angle to the floor. They may combine views of the earth, the moon, and Mars, while also combining modes of mapping and representation. They zoom in on surface features, group them in rectangles like screen shots, and then overflow the groups. They cover uninhabitable territory, including the South Pole, but they ask just what or who has shaped it. They are maps of the world, but also of late modern art.

Back from extinction

Are art galleries no more than relics of a bygone age, of lower rents and freer access, even as a handful of weathy galleries build higher and higher? If you are among the many who fear so, Central Booking has the show for you. "Fossil Tales" treats the gallery as a space for sediments and relics, like bones for Jean-Luc Moulène and a monkey for Mary Frank, each, as in Frank's latest work, with a real or imagined history. They might be actual fossils, like the dinosaur bones that Frank Ippolito has measured or the dinosaur eggs that Nina Kuo and Lorin Roser have modeled in clay. They might be the inspiration for drawings, paintings, and hangings or stand-ins for the artist. Yoon Cho in a photograph walks beside a layered cliff with images of skulls overhead, while Roser tapes Kuo as either a living fossil, a human embryo, or just fighting her way out of a plastic bag.

The gallery still devotes its front space to artist books, and at least three contributors to "Fossil Tales" adhere closely to the form as well. Patricia Olynyk's prehistory unfolds in an accordion book, Deborah and Glenn Doering offer the origins of the world in a primitive sign language, and Maddy Rosenberg translates the very idea of the fossil record into physical layers. Her photographs of a fossil in melting ice can slide in or out of a small wood box with a sliding cover. Barbara Rosenthal uses an illustration from a scientific study to lend her spread the feel of a textbook. Others work in a diversity of media—including colored pencil for Lynn Sures, gouache and watercolor for Desirée Alvarez, black and white for Steven Gawoski, stained cloth for Kathy Strauss, prints for Marilyn R. Rosenberg, paint for Sue Karnet, and encaustic for Elizabeth Hubler-Torrey. Her wax technique hints at preservation all by itself.

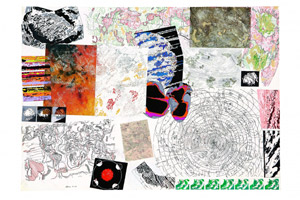

Gawoski's rich detail points to his source in microscopy. Others seek less the scientific method than a human presence. Sures sketches what could be flint tools, and the dinosaur eggs look much like skulls. Others, too, find that presence in the physical space of the gallery—with crumpled paper for Doug Beube, collage for C Bangs, embossed paper for Gerhild Ebel, a weathered chain for Alan Rosner, and a simulated bed of sand in salt and coffee grounds for Ursula Clark. It appears to bear a fossil imprint, but be careful where you step. Sarah Karnet passes her images through an old film editor, as if both early life and dated technology are ready for a second take.

Whenever art meets science, it risks reducing science to a metaphor. In this case, it is not a bad metaphor at that—quite apart from Karnet's pun, as the gallery puts it, on the ancient and antique. Central Booking is now a relic, too. This is its last show on the Lower East Side, joining a growing list of vanished galleries. It will attempt the hybrid model of art fairs and a smaller space for private dealing. That pretty much leaves just one public space for artist books, the Center for Book Arts, itself primarily a workspace.

It also leaves one less space devoted to the meeting of art and science. It has been cycling through one discipline after another, with Maddy as curator—including genetics, microbiology, math, data sets, and natural histories. (Disclaimer: I have supported the space, and it bears my name.) The image here shows, shall we say, a past specimen. I have trouble decrying the losses, given the obscene size of the art scene compared to the relic that I remember, but they are troubling all the same.

Second-guessing is easy. The front space may have discouraged critical attention, by making the gallery seem more like a gift shop. Then, too, group shows are a dime a dozen, and exhibitions have drawn on many of the same artists over time. On the other hand, the front space does well by its artists, and two more back spaces have allowed solo shows and well-attended events. The only certainty is that art still depends for its vitality on midlevel galleries like this one, rather than artist collectives on the one hand or the posh dealers that suck up established artists on the other. My thanks go out to the many that survive and even thrive.

Gonzalo Fonseca ran at the Noguchi Museum through March 11, 2018, "Fossil Tales" at Central Booking through March 25. Nancy Graves ran at Mitchell-Innes & Nash through April 6, 2019. A related review gives more space to Noguchi's garden museum.