10.7.25 — Battles to Fight

To pick up from last time, everything about Ben Shahn was serious, least of all The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti. No sooner had he completed that series, with twenty-three paintings, but he began another, of an Irish American labor leader convicted of a fatal bombing.

The first painting has entered the Whitney Museum and reached a wide audience. One might never know that he lived nearly forty more years. During that time, he was never close enough to Modernism. He was still making what postwar abstract art dismissed as “illustration.” Now the Jewish Museum calls for a reconsideration, as “On Nonconformity,” through October 23.

Maybe his refusal of modernity derives from his exposure to the brutality of a century. Maybe, too, it derives from the fate of an Eastern European Jew. Born in 1898 in present-day Lithuania, Ben Shahn came to New York with his family as a small child and settled in Williamsburg, Brooklyn long before its brief home to contemporary art. He had already endured plenty, but it seemed if anything to have him always looking for a home and promptly claiming it. As an adult he roamed all over with a camera, from parades, to Greenwich Village, and all the way to Alabama. He converts a photo of a handball game into a small painting that will feel like home to many a New York kid.

He returns to Judaism late in life, to set forth Ecclesiastes, the miracles of the Haggadah, or simply his appreciation of Moses Maimonides, the medieval Jewish scholar. Shahn has a gift for pairing text and imagery, pressing on one another without getting in each other’s way. It gives his retrospective a warm, handmade conclusion. He might be the artist always celebrating with a holiday or hallelujah. And maybe now I can see him that way. It might be better, though, to see him as out to reclaim art as highly serious.

Shahn kept up with his times in terms of battles to fight, but also who was fighting. He creates a frontispiece for E. E. Cummings, the poet and contributes to Edward Steichen for The Family of Man. He creates posters with iconic steel workers. A bit over half way through, in a section for cold-war anxiety, he sketches men in watercolor as The Existentialists. It looks back to a time when art, politics, and philosophy inspired one another. Think more recently of Postmodernism and deconstruction.

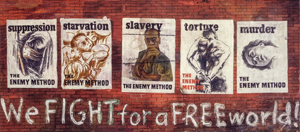

Existentialism has taken its licks over the years, and so has Shahn, though he still has hardly vanished. Keeping up with his times could not have been easy, for he lived in interesting times. And there he was, following every step of the way—from anarchism to the New Deal, the labor movement, world war, the Cold War, and postwar anxiety (with existentialists), and civil rights. He travels to India for Gandhi for tribute and South Africa with block type for breaking reports. He likes posters not just because they might make a difference, but also to press close to the picture plane. When he returns to Jewish subjects, you may wonder what he had left to celebrate.

Existentialism has taken its licks over the years, and so has Shahn, though he still has hardly vanished. Keeping up with his times could not have been easy, for he lived in interesting times. And there he was, following every step of the way—from anarchism to the New Deal, the labor movement, world war, the Cold War, and postwar anxiety (with existentialists), and civil rights. He travels to India for Gandhi for tribute and South Africa with block type for breaking reports. He likes posters not just because they might make a difference, but also to press close to the picture plane. When he returns to Jewish subjects, you may wonder what he had left to celebrate.

The curators, Laura Katzman with Stephen Brown, never need to choose between a chronological and a thematic arrangement. With news like this, they can have both. But if there is one constant, it is people—from the handball court on Houston Street to apartheid. The existentialists are standing figures, because they are exposing themselves and taking a stand. Shahn traces the Civil Rights movement through faces, most often of victims. If it is all too serious, it is your choice to look away—and I wrap up next time with Shahn’s status today.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.