10.31.25 — Equal Terms

Temitayo Ogunbiyi must be flattered. For its fortieth birthday, the Isamu Noguchi Museum asks her to bring her art to the United States—and I work this together with more recent reports on New York public sculpture as a longer review and my latest upload.

More impressive still, it invites her to enter on equal terms with Noguchi. She exhibits alongside him, their work toe to toe and face to face, through November 2. If you cannot quite say which of the old metaphors to apply, that is itself a tribute to what he brought to modern sculpture—and to what Ogunbiyi hopes for sculpture now.  This is not public sculpture, but New York summer sculpture all the same. If you have to head out to Astoria, on the Queens waterfront, to see it, no sculptor is more open than Noguchi to those who look.

This is not public sculpture, but New York summer sculpture all the same. If you have to head out to Astoria, on the Queens waterfront, to see it, no sculptor is more open than Noguchi to those who look.

Noguchi makes art far too responsive for a museum’s customary divisions into galleries and rooms. The Noguchi Museum calls its divisions just “areas.” Even with a map and the occasional wall label, you will find it hard to know where one area ends and the next begins. You might say the same, too, about borders to works of art, and Ogunbiyi addresses them directly. Entering past the front desk brings you to the same old, same old—a selection of his work pretty much exactly where it was. The newcomer just adds some of her own.

At first glance, the two do not have much obvious in common. Noguchi runs to massive objects resting firmly on the ground, obliterating the distinction between sculpture and its base. He works closely with materials like cast metal or carved stone, for coarse edges, a fine polish, or near uniform stippling. He rests content with the simplest of geometry or none at all. Ogunbiyi draws steel or copper rods into curves that start and end on the floor, before wrapping them in rope. Her meandering arches could pass for rope themselves, all set for rodeo tricks.

She is neither taking Noguchi as a model nor disdaining him, but rather making connections. Her rope might almost be tying them together, physically and visually, even as the work spills out past museum walls. In the process, their distinct styles start to look more and more alike. Noguchi turned eighty the year of her birth, in upstate New York in 1984, and did not have long to live. She moved to Philadelphia with her immigrant parents, from Jamaica and Nigeria, and has settled down in Lagos, Nigeria, a more populous city than New York. All the same, she might be thinking, “You Will Wonder If We Would Have Been Friends.”

I quote the exhibition title, named for a watercolor with touches of pen. Her reptilian curves appear flattened to the dimensions of paper—or to the ridges of a snail shell. She pays explicit homage by taking his shapes and materials as feet for sculptured curves as well. Like Noguchi, she makes no concessions to realism. Still, neither artist could mind if you describe sculpture in human or animal terms. It was, after all, once alive in the artist’s hands.

It may have human purposes as well. Ogunbiyi has also worked in playground design, at once art, architecture, and the molding of space itself. She says that she took an interest watching her daughter at play in Africa, but she must have known its interest for Noguchi as well. It brings out a shared sense of play, for all his monumentality and stillness, like that of his planned memorial to Hiroshima. The garden museum really is a privileged enclave and a place for contemplation, quite as much as the reopened Frick Collection on Fifth Avenue. If it has humbler and dirtier origins, with industry and Costco still across the street, Noguchi valued the everyday.

It may have human purposes as well. Ogunbiyi has also worked in playground design, at once art, architecture, and the molding of space itself. She says that she took an interest watching her daughter at play in Africa, but she must have known its interest for Noguchi as well. It brings out a shared sense of play, for all his monumentality and stillness, like that of his planned memorial to Hiroshima. The garden museum really is a privileged enclave and a place for contemplation, quite as much as the reopened Frick Collection on Fifth Avenue. If it has humbler and dirtier origins, with industry and Costco still across the street, Noguchi valued the everyday.

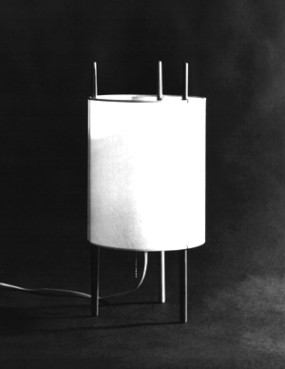

Ogunbiyi does bring a playground to Queens—not to the waterfront like Socrates Sculpture Park nearby, but right inside. She gets a small, separate room after all for just that. It looks much like the rest of her work, with three arches and two stone chairs. Kids could run free here, if not for the run of the show, but it might be tough. They could go for pull-ups using her arches, and never mind if they fail. Despite a thin fabric layer, parents would find hard seating as well. Such is the price of freedom.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.