4.16.25 — The Limits of Political Art

Can art bear witness to a massacre? This winter I wrote about artists who do, and they have me thinking about political art and whether, even for a progressive artist, a message of any kind risks conservatism in art.

Can form and content be at odds like that, and does it matter? Surely these artists hit home because their form and message alike aim for the eye and strike home to the gut. Before I say more about them, then, let me talk through the dilemma and the promise.  I did so many years ago with one of this Web site’s first essays, about an artist as in command of silence as Jan Vermeer—and yet even his women seem just about to speak? What would they say about art now? Now I wrap this in with the winter’s reports on Enzo Camacho, Ami Lien, Sohrab Hura, and Marco Brambilla as a longer review and my latest upload.

I did so many years ago with one of this Web site’s first essays, about an artist as in command of silence as Jan Vermeer—and yet even his women seem just about to speak? What would they say about art now? Now I wrap this in with the winter’s reports on Enzo Camacho, Ami Lien, Sohrab Hura, and Marco Brambilla as a longer review and my latest upload.

Just to ask about such matters could serve as a frame for any discussion of political art. Not only political artists will feel strongly about it. So many, in every genre and medium, will speak of finding something more in what they do than a message. I would be wrong to write this off as formalism or, conversely, an overriding need for self-expression. A generation of late modern artists and postmodern critics dismissed all that came before as likely both, even as much of the public dismissed abstraction, conceptual art, and the present. We were not going to be like that, because we were not going to give up on art.

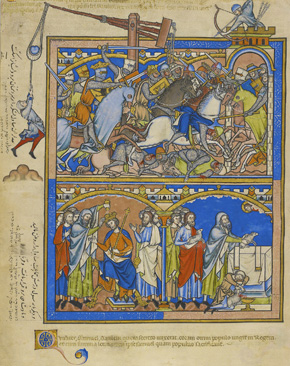

Still, it is only fair to insist that not just political art, but most art, maybe all art, has a subtext not to be dismissed. How often art that had seemed remote to me became vivid once I read more about it. I had not appreciated the depth and shimmer of oil colors in Jan van Eyck and the Northern Renaissance until art historians like Erwin Panofsky taught me their iconography, the stories they set out to tell. It was important not just, as artists themselves might suggest, because it caused me to look longer—long enough to start to see. Without it, the liquid darkness in Francisco de Goya and Disasters of War might have seemed a pale excuse for monochrome abstraction. With it, that darkness became a reason to look and a reason to paint.

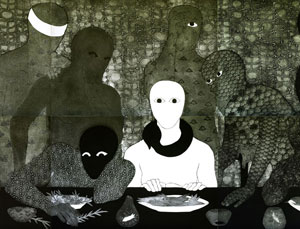

Consider an artist whose politics extends well beyond her art. In All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, the film about Nan Goldin, a three-part narrative advances along parallel tracks throughout. The very first sequence speaks of the suicide of her sister, and the story continues to ground her work in her life with all its pain and triumph. The second track takes up her major work, the slideshow The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, in all its closeness to her but also its silence. These are her friends and loved ones in the age of AIDS, and one can only guess who in a photo is dying or a survivor. One can only guess, too, which of the couples sharing a frame can overcome their physical and emotional distance.

The third track ups the ante on both those narratives, her life and her life’s work. It shows her as an activist backed by a movement. Their assault on the pharmaceutical industry advances, obliging museums to refuse tainted funding. And yet this last track will never fully engage a world outside of art institutions, and it all but gives up on art. Can political art, then, still make a difference? Did it ever?

As an undergraduate, a friend told me, he sought an answer in a hole in the ground. Joel Shapiro, the sculptor, asked his students for two works apiece, one sincere and one false, but forget that. For each, my friend dug much the same two holes in the program’s yard, three by three by three. He started with the false one, but by the time he had turned up all that soil the false had become true. He might have felt a personal obligation or a personal violation in filling them up again.

At art’s most rewarding, the artist’s ideology is part of the work, too, intended or not. Whether politics, religion, or belief in itself, it develops right along with the visual and material. I think of existence and subtext as a bit like music and lyrics, and there is no point in making songs into lesser symphonies. The subtext can be what gets the artist up in the morning, throwing paint at canvas, or to bed in the evening, contemplating every detail, and it can raise other subtexts as well, like as the artist’s disturbing passions. It is a writer’s job to tease all these out and to show that form and content are alike part of the work, the very same work, and just what that entails. What goes wrong with bad political art may be that they never really are.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.