10.10.25 — Brooklyn to the World

To wrap up from last time, Ben Shahn has fallen out of favor regardless—and not just because art moved on to abstraction. Nor is it that he refused the past century.

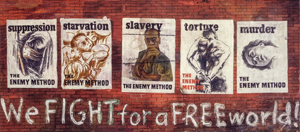

That sketch of existentialists approaches the stark, jumbled planes and predominant reddish blue of Analytic Cubism. It just happens to take until the 1950s to appear. There is no getting around that posters are meant as propaganda. That great opening painting of Sacco and Vanzetti looks like a poster.

For one thing, he was out of step with the dominant media of his time. He disliked oil paint for its high gloss. He preferred tempera, from the Renaissance, with its soft matte colors, and he treated the thickness of gouache on an equal part with the transparency of watercolor. Just as much, he seems content with what he sees. You may be surprised at how much his painting of a handball court sticks to the photograph. In the two opening series, family members stand around facing stiffly front as in a selfie.

Of course, being told what to believe, even by someone rebelling against what others tell you to believe, can be cumulatively fatiguing. But Shahn runs the opposite danger. In his deep human sympathies and limited means, he risks not presenting a judgment. Everyone shares much the same grim look. Is that a way to convey the torment of J. Robert Oppenheimer after the bomb? Does it find humanity in the worst and guilt in everyone? Maybe, but I am not so sure.

In part, it reflects no more than Shahn’s moral sophistication and the moral complexity of his time. Like the rest of America, he had to adjust from the evils of war to the fight against evil and back again, and no one did it better. In part, though, he was just not that clear. He poses President Truman on a piano, carrying on with Thomas E. Dewey, his 1948 opponent, at the piano. Boys in power will be boys. But then Shahn thinks better of it and shifts to the Republicans alone.

What does he think of the Supreme Court? In the course of civil rights, he wanted to celebrate Brown v. Board of Education by picturing the justices. And so he does, seated side by side on the bench. They have the same blankness as the family of anarchists so long before, and they share much the same classical edifice as The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti. Detachment and ambiguity are extraordinary virtues, and Shahn had them. I could not help wondering, though, whether he had fallen into them through his limitations as an artist and his need to be serious, start to finish.

He leaves an impression all the same. His show becomes a testament to others and a newsreel of his century. It is hard to resist jumping back and forth to see it afresh. In a show whose last section is “Spiritualism and Identity,” what then has finally changed? Think of all his work as defining his identity and politics as his spiritualism. Think of his circles as expanding outward from Brooklyn to the world.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.