7.18.25 — Impressionism into Theater

I kept things short last time on John Singer Sargent at the Met, because he has been a subject, for both me and museums, so many times. But do follow the links to more, and here I offer an excerpt as an introduction.

When “Sargent Paints a Child,” the subject of a 2004 show at the Brooklyn Museum, adults hover everywhere. They are the parents—most often mothers, of course—putting on display for all to see their love, their duty, or their glamour. They are the unseen fathers, men whose wealth commissioned full-length portraits even for their sons and daughters, men whose status in society demanded it.

They are the adults these children were to become, shaped by a life of privilege and their few moments indeed away from its spotlight. They are the adults their parents expected them to become, carrying on roles and responsibilities known by heart. They are the adults the children wanted or feared to become, almost from birth. They are the actual young adults, reveling in the discovery of increasing freedom and sexual magnetism. And then there is another adult, Sargent himself, the self-styled man of the world who understood when a sitter’s name—and his own—turned on pushing those roles to their extreme. He is seeking out and questioning the shrinking space left for innocence by late Victorian culture.

That space resonates today. Think of the endless baby pictures passed around by digital camera and the Web. Then think of the constant assault of sexually charged material that kids see everywhere. Think, too, of the sheer proliferation of images, so that consumer choice becomes a choice of what role to play. Sargent could have been the first hipster, without ever setting foot in Brooklyn. He practically dares one to look behind the scenes—only to find that nothing is there.

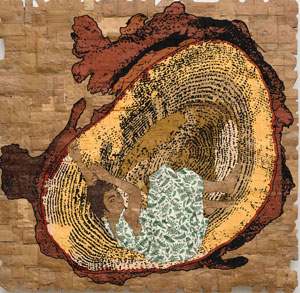

As for Impressionism, he had neither the subject matter nor the technique. Where Pierre-Auguste Renoir or Claude Monet gave expression to a new middle-class leisure, often their own, he preferred summers in the Alps. And for the painter who adapted Impressionism for Americans abroad, he all but eliminated its heart—the construction of space and light through color. He does not set pigments side by side, for optical mixing. He washes colors into one another, alongside those dazzling whites, to get whatever hue, intensity, and darkness he liked. It transforms Impressionism into theater.

He grounds sitters in their social class, but he takes away any solid ground beneath one’s feet. A strong, frontal light flatters a boy, but also flattens him. Fluttering, red brushwork on the wall behind thrusts him unnaturally forward, and it accentuates his looming shadow. In a frontal portrait, a girl’s delicate white dress, the decorative wood paneling behind her, and her fixed stare right through the viewer make her float in front of the canvas. She seems doubly haunted, by the childhood she is leaving behind and by something more ghostlike in her future. But then too much finish was always a betrayal of Sargent’s art.

When adults turn up, the multiple centers of attention can become serious conflicts of interest. In a birthday scene, one sees first the dark, ill-defined shape of the father. Only then does one notice the mother, massive and dominant, cutting the cake. Finally one spots the child, off to the side, blowing out the candles, one year older now and lit from below by the flames. Remember as a kid holding a flashlight below your chin? Growing up is spooky.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.