9.1.25 — Awakenings

In reviewing “Vermeer’s Love Letters” at the Frick Collection, I tried to stick closely to the exhibition’s three paintings. I had written often about Jan Vermeer, a favorite, in the course of thirty years, including a review of his 1996 Washington retrospective, so I kept focused on the exhibition, relying on past reviews for a fuller picture. Allow me here to except from the first and longest as a brief guide and a teaser.

So little seems to be going on—a woman alone in a private room, few props, no motion, no overt emotion, the letter itself a slim ribbon of light. Jan Vermeer makes no fuss about what she might be reading, what it means to her, and why it deserves to be painted. He seems to lavish all the subtleties of a great colorist and observer on next to nothing.

So little seems to be going on—a woman alone in a private room, few props, no motion, no overt emotion, the letter itself a slim ribbon of light. Jan Vermeer makes no fuss about what she might be reading, what it means to her, and why it deserves to be painted. He seems to lavish all the subtleties of a great colorist and observer on next to nothing.

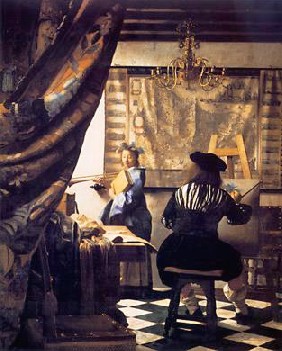

I keep looking for meaning in Vermeer’s gestures. And I keep returning to the same characteristics—reflected light, intricate but confined spaces, and the slow movement of the eye across a flat surface. He captures only the nuances of reflected light, the edges of a stark room of indefinite dimensions, and a surface almost compulsively divided by a window pane and green curtain. Its implied grid calls to mind the explicit cast-iron grid of the window. In his Milkmaid from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, a blemish in the wall captures the light. In room after room of his retrospective, they have filled a museum with clarity and light.

It is an old debate: is art best defined as symbol making or as something that resists interpretation? Does its allegory have a subtext? Has contemporary art triumphed over old narratives with “pure painting,” or is it telling new stories entirely? Do true artists never explain their work, or are they the only ones with the right to try? Both sides beg for the vast institution called art history, and neither side is ready to ask how uniform and coherent that institution really is.

But can labels begin to explain a painting that will not let anyone read its letter? No wonder Jan Vermeer is known as the painter’s painter, the one who most avoids associations with the transient and the insignificant. For many modern admirers the word anecdotal, mere storytelling, is an insult—and an allegory a thing of the distant past. A nearby Dutch interior by another fine artist, Gerrit Dou, could indeed be the anecdotal version. I can enjoy it, but I could stare far longer at Vermeer’s warm, even light. I could feel time pass as it slips from window to wall to her face, then back again to her reflection in the window.

Vermeer keeps returning to women awakening to adulthood. They all struggle to manage their sexuality, self-esteem, and some dubious male propositions. A woman at a window raises her pearls or turns her gaze toward the warm, enveloping light. Another woman hides her face in a drink. I do much the same at parties now. In a later painting, a man again leans over a woman’s shoulder. She looks out, toward the viewer, with a grin somewhere between dazed, ill at ease, and inane. And still they retain that sense of wonder behind the apparent reserve.

Maybe Vermeer is the ultimate postmodernist. His women hold a letter the way a saint might hold the instrument of her doom or her miracle. Like a saint, too, she is left with the same demand to think about her virtue and her fate. Religious painters had used props to evoke texts that had already become canonical. Vermeer creates an artistic canon from a fictitious text and makes that text emblematic of his art.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.