Photography in the Anthropocene

John Haberin New York City

Edward Burtynsky and Wanderings

What makes a photograph worth keeping? Is it something special—that special place, that special person, that special time?

True, the story goes, some collectors disdain photography as something anyone can do and too often does, before posting it online. Others, though, know just where to point and what to shoot on their way to the decisive moment. Sound awfully romantic? Edward Burtynsky goes that ideal one better. For fifty years now, he has been the first to think of not just what to shoot and what to print, but what to see. It could be somewhere that you could never reach or never wish to go. And he is in a hurry to get there, just in time for "The Great Acceleration," at the International Center of Photography.

Born in 1955, Burtynsky has been seemingly everywhere. He is not, though, nostalgic for any of it and not in the least romantic. He is mapping, ICP says, "human alteration of natural landscapes around the world," in an age that some call the anthropocene—meaning people front and center, effacing the natural world and remaking the planet. If you are not altogether sure whether that alteration is a great or a terrible thing, neither is he. Together with Sheida Soleimani, a refugee from half the planet away also at ICP, he wrestles with a bittersweet future. He is not looking away and not looking back.

Burtynsky is out to see what no one has seen in more than one way, starting by just being there. He has seen ship breaking in Bangladesh and auto wrecking in Arizona. He has reached textile factories in China, oil fields in Azerbaijan, sawmills in Nigeria, and silver mines in Mexico. Humanity, he explains, has come out of Africa, and now it has come "full circle." He sees what no one has seen as well because too many have refused to see it. These are things of huge commercial value but disdained as the very name of garbage, like salt deposits, uranium tailings, nickel spills, and what they lay to waste.

As a follow up, a return to ICP finds less industrial waste and less virtuosity. It calls just one of its year-end shows "Wanderings," but all three bring people together who are going nowhere fast. I cannot swear to the power of Graciela Iturbide, Naima Green, and Sergio Larrain as photographers. They might belong together only by hanging loosely apart, through January 12. They do, though, put documentary and portrait photography through their paces, to the point of daring you to tell them apart. That may or may not be such a good thing.

A confusion of shadows

Edward Burtynsky sees what others cannot because of where he stands. The Canadian adopted a high vantage point, sometimes from digital cameras and helicopters, even before he took to drones, where no one at all is exactly doing the seeing. His technological prowess has only increased over the years, with such devices as gyroscopes to stabilize flight. He is documenting technological advances, if you wish to call them that, as well. It makes the surface of the earth his canvas, with painterly images, and do not even ask who is painting. They can be wildly expressive, like the free curves of rice terraces in Asia, or startlingly geometric, with long bands and concentric or overlapping circles.

The curator, David Campany, suggests the influence of Abstract Expressionism on the camera's "all over" picture. John Chamberlain, after all, made expressive use of auto wrecks, too. Chamberlain helped to initiate a further change in art, too, toward the commercial objects of James Rosenquist and Pop Art. Burtynsky's subjects include a positive riot of brand names in Pennsylvania—including McDonald's, Starbucks, Exxon, and Walmart. They could be competing to claim the intersection as their own or the entire earth. It has, Campany adds, an "unsettling beauty."

I started this review with a sentimental ideal about photography and proper art, but neither I nor Burtynsky necessarily shares it, not any more. He is not Henri Cartier-Bresson this late in the day in search of that "decisive moment." Rather, he gains in relevance for what many before Andy Warhol once disdained, repetition and reproduction. He is not above decisive places and events, like Mount St. Helens after eruption, but he prefers subjects that retain their anonymity, as a window onto the everyday. He sees industrial transformation as a transformation in society and in human lives. It could be the price of a so-called free market or, in China, an instrument of the state.

Burtynsky calls one series Natural Order, with obvious irony, but he may not have to choose between ideals—or between ideals and no ideal at all. He is demanding that people observe and take responsibility for what is lost while responding personally to an endangered beauty. He likes the landscape best at noon, he says, for the "confusion of shadows." He loves detail, like tiny holes in the land that appear only up close, or a field of black rubber tires. He prints big and in diptychs, to leave you asking just what is at all natural. He makes it hard to identify the subject or point of view.

Sweeping curves could belong to a highway or to erosion from frighteningly toxic waste. A salt river blends easily into suburbia and farming into tailings. People find work creating waste, but also in cleaning up. Sharp color is irregular and rare. (Who would waste good money on color in a prefab development?) Yet it and, for that matter, so much else could pass for touch-ups after the fact from a painter with a gifted hand.

If this is the anthropocene, with people as its ends and means, what counts as human? By far the most photos are devoid of people—and that confusion, too is a fact of modern life. Burtynsky treats some scenes as portraits of industrial and post-industrial workers, in leisure moments and numbing labor. But landscapes are for him a kind of portrait all by themselves. Burtynsky allows himself few signs of pain and plenty of bombast, but he is fine with that. There is a tempting beauty in a confusion of shadows.

Hanging loose

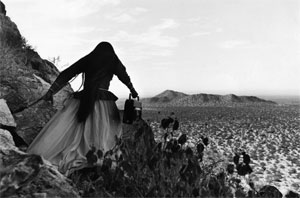

Burtynsky's successors at ICP belong to three generations and to places as far apart as Central and South America, Europe, and the United States. Graciela Iturbide photographs women as shadows with their back to the camera, looming, while the others look to their companions for company. She speaks of her subjects as caught in rituals of celebration and death, but which is which? Women lean forward, arms spread wide like an angel's, a bat's, or a demon's, accompanied by a skull. The may share a desert landscape with dozens of anonymous others—or assume the greater luxury of Oxaca Botanic Gardens and Mexico City, where she learned photography herself. As curated by Carlos Gollonet, this is "Serious Play."

People here compete to appear as individuals or as symbols of a doomed Mexico. She has a debt to return to the nation, all the while knowing that what she photographs is gone.  Series run through the 1960s and 1970s, including one on the track of Frida Kahlo. She sticks entirely to Kahlo's bathroom, where a poster of Joseph Stalin remains. It is not welcoming, but then you never can find a bathroom when you need one. She travels to Cuba, Panama, India, and Argentina as well, with support from Fundación MAPFRE.

Series run through the 1960s and 1970s, including one on the track of Frida Kahlo. She sticks entirely to Kahlo's bathroom, where a poster of Joseph Stalin remains. It is not welcoming, but then you never can find a bathroom when you need one. She travels to Cuba, Panama, India, and Argentina as well, with support from Fundación MAPFRE.

These photographs see art as political and politics as gendered. Her best-known series, published as Juchitán de las Mujeres, imaginea Juchitán, a rural community, as a place of mujeres, or women. Naima Green sticks to women, too, for her subject is pregnancy today. As curated by Elisabeth Sherman of the Museum of the City of New York, she reduces it to the "concept of pregnancy"—evoked, she swears, through, through landscape and self-portrait. I make no promises.

Still, women get their due, like Aunt Dot in her kitchen. Pregnant women pose together, if you can call this posing. They can admit their vulnerability as well. "I multiply, says a photograph," and "I shatter." They are vulnerable as well crispness of Green's colors and a wall-length photo-mural. I Spin Fantasies, a title says.

As for men, you will just have to venture back sixty years to Sergio Larrain. His photos are open to adults and children, woman and boys, but above all wanderings. They include series set in London, Paris, Valparaiso, and Peru—and to Vagabond Children. Their subjects may appear in close-up or as distant cousins of Green's pregnant woman, doing their best to sustain a pose. They are, though, always in motion as Iturbide's or Green's will never be. She can do only so much, but it will get you going all the same.

Their photographs leave plenty of room for impulse and for video. They are cousins, too, to rebels and vagabonds in film of those years by Jean-Luc Godard. They hop on and off buses and trains. All of them normally reside in Magnum archives, curated by Agnès Sire, former director of Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson. Does that have you thinking of documentary photography and the decisive moment? All three photographers are just hanging out.

Edward Burtynsky ran at the International Center of Photography through September 28, 2025, with a summer show at Howard Greenberg, "Wanderings" at ICP through January 12, 2026.