Everyday Heroes

John Haberin New York City

Emma Amos

Emma Amos walks a tightrope, as a black woman and as an artist. Does that make her a superhero? One might think so from her imagery at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but she is not alone. The company she keeps includes friends and forebears, and a follow-up in the galleries highlights her family odyssey. Here everyday heroes matter most.

When the Philadelphia Museum of Art called its retrospective "Color Odyssey," it meant hers, of course, as a woman of color and an artist. Still, nothing for Amos is just about her. It is about friends, and the museum went big on her portraits. It is about family and race, and ten monoprints follow them both from the end of slavery to the present. Now in Chelsea, that series is about western culture as well, black and white, and she named it after a truly classical legacy, The Odyssey. It seems only right, though, that it concludes with her.

Tradition and activism

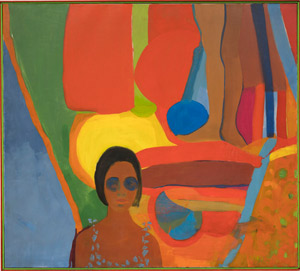

Amos broke through in the 1960s with portraits of friends, proud but hardly comfortable. They appear out to share their discomfort at that—or to make the viewer uncomfortable by thrusting it in one's face. More than one leans forward, while Baby has baby blue eyes wide and in command, unless, that is, they are bottle glasses covering her plain features and inability to smile. They also match blue circles in the wild abstraction behind her. Are they interior decor or what the artist should be doing, if only she could admit it? She liked to say that color was always political, but then, one might add, so was a black woman at leisure or at sea.

She was always an artist and an activist, putting both first. Born in 1937 in Atlanta, she studied painting in Ohio—abstract painting, like that glorious background and like art at the leading edge of her time. The museum includes a lone example from the 1950s, but then she moved on, first to London and then settling in New York. One portrait takes its title from the street. Yet she also learned weaving, which gives many an unstretched canvas its lush but ragged borders. She could not have foreseen today's fashion for art as craft and tapestry as painting, but she must have known a traditional African American woman's work, as with Gee's Bend quilting, as a source of color.

Amos took both activism and tradition seriously. She joined Spiral, a short-lived response to the 1963 March on Washington but still a movement in painting. A co-founder, Hale Woodruff, was born in 1900—ten years older than Romare Bearden and old enough to know the Harlem Renaissance at first hand. She also joined the Guerrilla Girls, but with little of its distrust of art. She had a perfectly respectable teaching career at that. She had a broader ancestry as an artist as well.

She called a 1993 work, of strange bodies and stranger fruit, Malcolm X, Malcolm Morley, Matisse, and Me. Surely Malcolm X had other things on his mind than Morley's casual British realism—or the deeper colors and deep-seated Modernism of Henri Matisse. Amos, though, had equal concern for them all. One might see Matisse interiors behind the flattening of those early portraits. With another artist, one might be speaking of the tensions in her life and work. She was way too self-aware for that. She could keep in her head a healthy respect and a healthy sense of humor.

She could also keep her delicate balance, with Tightrope in 1994. A sweeping black robe opens to reveal her role as a superhero, dressed as Wonder Woman. Go ahead and laugh, for she will, too, just not on a tightrope. She walks confidently with a brush in one hand and a coat hanger in the other with an alternative costume. It could be a t-shirt bearing an image after Paul Gauguin, of a Tahitian woman's crossed arms holding fruit, but with more pointed breasts and paler flesh. Then again, it could be a 3D mask for a black woman obliged to pass as demure and white.

She could be making fun of white artists, Western artists, and herself, but I would not be too sure. The brush in her hand is way too small and fine for this kind of work, but all the more a boast for that. The black robe cannot hide her costume, her pride, or her imperfections. Nor can it disguise the bright yellow floor encrusted with seeming jewels and the backdrop in black, blue, more jewels, and white. She may be staking her life on a circus act, the perils and glories of the night, or firm ground. Amos may walk a fine line, but she is well grounded.

From portraits to masks

Philadelphia has a modest retrospective, past a wall painting by Odili Donald Odita and on the way to photographs by Richard Benson. It works well, though, with just four rooms as guides to stages in a modest career. The curators, Laurel Garber with Theresa A. Cunningham, call it "Color Odyssey," which singles out the role of color, but makes a little too much of the odyssey. For all her changes, Amos seems by no means eager to overcome past obstacles. They drive her forward to the end, with her death in 2020. She calls a painting How to Mourn, but who has time for mourning?

Her portrait stage has its discomforts, but still among friends, as in an earlier show of "Spilling Over" into color. A twin portrait captures Sandy and her husband in a slow dance, and one can feel the love. What, though, should one make of a third person in an oval behind them, concerned only for herself? Is it, too, a painting or rather a mirror that disdains to reflect what it sees? Other titles include Godzilla and Creatures of the Night. They are just women, but women come with all sorts of expectations.

Her portrait stage has its discomforts, but still among friends, as in an earlier show of "Spilling Over" into color. A twin portrait captures Sandy and her husband in a slow dance, and one can feel the love. What, though, should one make of a third person in an oval behind them, concerned only for herself? Is it, too, a painting or rather a mirror that disdains to reflect what it sees? Other titles include Godzilla and Creatures of the Night. They are just women, but women come with all sorts of expectations.

Next come works on paper that show a dual concern for the craft and the women. Amos pulps paper before reusing it, to represent the medium itself and the texture of flesh—all those tiny spots that traditional female nudes cannot see. A black woman from 1966 is an American Girl, where white eyes may be unable to see. Finally come the 1990s, with a sudden rush of color and space after the muter shades and flatness. The still poses also give way to bodies in motion. The artist claims Matisse the very moment that she leaves his most obvious influence behind.

One room is all about motion, with athletes and African Americans at leisure. It also places black and white women side by side, as All I Know of Wonder. It favors inclusiveness over solidarity. Others take to the air. Still, one may wonder whether they are flying or falling. A black man could be embracing a woman or abducting her, as Target, but it is he who shows fear of the lush colors behind them.

The largest room takes up the dilemma of influences and identity—but again without undue judging or losing its sense of humor. Disguises are hard either to lose or to maintain. A white face appears as a mask for a black woman, while Warhol in his blond wig shares a wall with the brothers Malcolm. Black silhouettes compete with Greco-Roman sculpture. Prominent African Americans include Paul Robeson and Thurgood Marshall, but also Clarence Thomas. Amos can take pride in a great deal, but not in everything.

One last influence goes unmentioned, or was I only imagining it? Window blinds had me thinking of the stripes in a flag for Jasper Johns, while those bottle glasses had me thinking of the blind eyes in his A Critic Sees. Was it just my imagination after the Johns retrospective a floor above? Perhaps, but a target enters Target, and blood red slashes across an amalgam of the Union and Confederate flags, as X Flag in 1992. White artists can be kindred spirits for Amos, but there are still things that they are unable to see.

A family odyssey

Amos created Odyssey in 1988 for a museum in Atlanta, the city of her family. A series that begins with an open book by Zora Neale Hurston (a family friend) cannot be just about her—although it contains her personal mark-up, in red pen. But then her family made history. Her grandfather became the state's first black pharmacist, and a spread from The Dixie Pharmaceutical Journal (ouch) shows him amid white professionals, who made a pilgrimage to see him. Her father took up his father's business, and her mother, with a degree in anthropology, ran the store. Still, a black family knew exclusions, and it is up to the artist to make them visible and to set them free.

Just eighteen months after her retrospective, the series emerges for the first time in roughly thirty years—the first since it showed here in New York at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Its recovery cannot match her retrospective. It can, though, supply an enormous missing piece. Odyssey has the front room, so that the additional work, much of it from the same years, comes as context. It includes what she called "Falling Figures" and the gallery "Classical Legacies." Still, the prints cannot help standing out.

While the images are not life size, the prints sure are, with an overlay of paint and glitter. They can be as colorful as the early portraits in Philadelphia. Here, though, her colors shine brightest when casually applied. Photo transfers attest to a large family, seated and most at home with one another. In between, figures float freely in the indefinite space of memory. That includes Amos in a flowing dress, looking younger than her fifty years.

That spatial motif recurs often in paint, and so do the classics. Billie Holiday swims toward Leda and the swan. In the show's largest painting, Flying Circus (also from 1988), acrobats command the sky while a swimmer goes deep, perhaps too deep. A singer plays the lyre, like Orpheus in myth, and white horses charge forward, as if at ancient Rome's Circus Maximus, leaving their only rider behind. Two figures, black and white, stand in uneasy proximity on an imagined Grecian urn. Amos did start as an abstract painter, but who knew that the transition to realism would come in 1960 with coarse black marks after the ruins of Pompeii?

Amos spent due time in Europe. For her, though, the classics need be neither ancient nor white. Homer had his Odyssey, but then so did Romare Bearden, whom she knew well from Spiral. Then, too, it is hard to think of a black odyssey apart from the Great Migration—or the Migration Series by Jacob Lawrence. As James Joyce put it in Ulysses, "Longest way around is the shortest way home." Amos is always heading home.

She may be dense with allusions, but not as a burden on the viewer. By the very nature of memory, one need not pin them down. They float freely much like her colors, between high and low culture and between real and imagined space. The next-to-last print in Odyssey contains cop cars and the KKK, and her ancestors surely knew them both all too well. Yet she ends hopefully with Freedom March—here not a collective act, but Muhammad Ali standing alone. The artist herself is walking her dogs and striding high.

Emma Amos ran at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through January 17, 2022, and at Ryan Lee through September 9, 2023.