Shallow Waters

John Haberin New York City

David Hockney

An ode to California swimming pools began in the public toilets of London. For David Hockney, they were dark places indeed, but also the start of a career among the glitterati.

It makes sense, even if you know Hockney only for painting sunlight, blue waters, and luxury homes with views to die for. From the start, he had a knack for infiltrating public and private spaces. And he took them as the site of both licit and illicit pleasures. A Met retrospective follows him for nearly sixty years, as his work grows progressively brighter, more colorful, and more than a step above the underground. It shows the knack for high style that has made him as popular as any artist alive. It also shows him navigating treacherously shallow waters, whether in backyard pools, toilets, or his art.

It takes a consummate draftsperson to skim over the surface. Think of Andy Warhol and his start in commercial art. And it takes someone who cannot look away from the surface to face up to age. Hockney could hardly help settling in LA, the land of eternal sunshine, but he could not leave behind the faces that meant most to him and what they endured. His portraits at the Morgan Library show a more caring artist than I had known, although still Hockney, as "Drawing from Life." It is not just how old you are in your heart, but on paper and in the flesh.

Licit and illicit pleasures

David Hockney made a splash right away, as a student at the Royal College of Art in 1960. Like R. B. Kitaj in London, he dressed well, painted quickly, and exhibited to acclaim. Yet he started with nothing like pristine waters and wide open spaces, and he could not even be bothered to write the essays needed to graduate. His early paintings border on abstraction, but with broad hints of male bodies. Did he really cruise the toilets of the London underground? I leave that to his biographers, but he had to know men who did, at a time when sex acts could get them all in jail. Besides, he could have spotted CUM as a poem on the underground walls and heard whispers of Shame and My Brother Is Only Seventeen—both the titles of paintings.

He also demonstrated his conservative instincts, even on the cutting edge or the edge of the law. A man does the cha-cha against heavy, acrid colors that Americans like Willem de Kooning were learning to leave behind. The first scrawls and splashes owe something to Jackson Pollock, through the eyes of more cautious English painters in Pollock's wake. Yet they anticipate street art, too, from Jean-Michel Basquiat on, and Hockney has a Pop Art sensibility as well when he converts penises into tubes of Colgate. Like the men dancing or managing to suck one another's toothpaste, he is having fun. This may be dangerous territory, but never once painful or grim.

Hockney will be like that for decades to come, only more so. Born in Yorkshire in 1937, he could stand for the reticence and realism of much British art. He could also stand for the bright lights and shallow pleasures of LA art, starting with his first visit in 1963. He has complained about art's abandonment of tradition since Andy Warhol, much like Robert Hughes. Yet he has sketched Warhol's portrait, and he comes as close as humanly possible to the Andy Warhol of the Hollywood Hills. Not even Warhol's entourage could have matched the crowds at the Met's press preview.

He has been a courageously gay artist, like Robert Rauschenberg. Yet Hockney hardly agonizes over it or anything else, and he is thoroughly at home among patrons straight and gay. His double portraits from around 1970 often become triple or quadruple portraits—like a young couple with a cat or collectors with their totem and Henry Moore. They sit tensely and stiffly apart, like figures out of Francis Bacon, but they are living flamboyantly and well. The artist also places himself squarely among them. When Henry Geldzahler, already a fabled curator at the Met, uses his portrait to contemplate works by Jan Vermeer, Piero della Francesca, Vincent van Gogh, and (I think) Pierre Bonnard, Hockney is laying claim to their company as well.

He is a perpetual experimenter—within carefully chosen limits. He depicts himself hurtling headlong through the Alps by car, and he takes pride in having seen nothing of the scenery. But then he must have seen more than he let on, even in 1962. He assembles dozens of small photographs of his mother in front of a ruined English cathedral in 1982, never quite disrupting the view of two aged beauties. He sides with dubious claims of Vermeer's reliance on a camera obscura—not just to investigate the nature of vision, but for mechanical tracing. And then he traces the image in a camera obscura for his art.

No other artist can seem as mechanical or as spoiled. He moves easily between his coastal studio in England and the la-la land of "movie studios and beautiful, semi-naked pictures." He never breaks the façade of either one and never once breaks a sweat. He quotes influences from J. A. D. Ingres to Paul Cézanne and Cézanne drawing while hardly stopping to take them in. He projects the comforting pleasures of both participant and voyeur. Yet his late work brings Henri Matisse fully and deliriously into the twenty-first century.

No stop ahead

You may find yourself a voyeur, too, passing quickly from room to room. No matter, for others, too, will be taking in the view. The second room bids farewell to London in more ways than one. It takes him from the closed space of public toilets to that of a stage, with roles for men bathing or a hypnotist and his subject. It also takes him on his trips through the Alps and to the coast of France, before his move to America. From this point on, his theater offers privileged views of the great outdoors, with just a hint of Modernism in home furnishings and the office buildings of LA.

His pleasures have not changed, only the pleasured. The bathers become a man in a more luxuriant shower, and the stage set becomes the swimming pools, much as for Michael Hurson or Katherine Bradford. The shower is running, a diver is making another big splash, and sprinklers enact the hissing of summer lawns. They point to painting as a moment in time, and the curators, Ian Alteveer with Meredith Brown, quote his fascination that painting takes so long to capture a moment.  It marks his first experiment with point of view, although here temporal rather than spatial. He shows the same interest when he paints a flower on a window sill with a mountain view—a tribute at once to casual interior decor and Japanese art's thoughts on eternity.

It marks his first experiment with point of view, although here temporal rather than spatial. He shows the same interest when he paints a flower on a window sill with a mountain view—a tribute at once to casual interior decor and Japanese art's thoughts on eternity.

The double portraits slow things further, in scrupulously clean surroundings, and then pencil and watercolor speed things up. Like so much else, his sketches show little evolution over a good thirty years. They also show little interest in pictorial space or psychology, but interest is building nonetheless. They share a room at the Met with the photo assemblies. From this point on, Hockney turns away from explicitly gay themes, but he is still looking around. The point of view becomes still more private, but the space starts to extend well beyond a swimming pool.

Hockney attributes his newfound impatience to the Met's Pablo Picasso retrospective in 1980. He finds a kindred spirit in Picasso's turn from Cubism to a playful realism, in the 1956 Vollard Suite. He may have found a kindred spirit, too, in Picasso's sexual exploits late in life. Regardless, the "Very New" (or just VN) paintings of 1992 do more than ever to throw caution to the winds. Foregrounds and backgrounds break in every direction, to the point of abstraction. Short verticals could stand for bushes, trees, gravestones, or just color for its own sake.

The newly intense colors settle into orange, red, blue, and green interrupted by dappled fields, for the Grand Canyon and Yorkshire broken across several panels. They also signal fresh attention to van Gogh. So does a long, unsteady view down an endless roadway. The last room brings what he calls his "Matisse colors," twisting along a not quite horizontal porch overlooking an enclosed garden. They recall the red of Matisse's Dance and the scale of Matisse cutouts. They also raise the question of what sets Matisse's joy in life apart from LA.

You may not stop to worry all that much over the difference, not in a show like this. Yet Hockney has a far more headlong and satisfied sensibility, in a more headlong and satisfied place and time. He has his equivalent of Matisse's scissors in his iPad, as a tool for drawing and animations. (He has also worked with Xerox and fax machines, never afraid of repeating himself.) A photo assembly of the Pacific Coast Highway has no end of warnings of a stop ahead. To his credit and his peril, he ignores them all.

Aging well

More than sixty years of portraits begin and end with Hockney himself, which makes perfect sense for someone who can never stop drawing. (As he puts it, he is always available.) He is the teenager in the north of England, daring anyone to look back. And then he is the old man always looking for his glasses, and that makes sense, too, for someone who looks to the truth in what he sees. He will try anything, including the iPhone—pouting, grimacing, and working at top speed to keep up with himself. Like Jean-Jacques Lequeu at the Morgan just months before, he has to put on a lot of acts to miss none of the comedy or the drama.

Not that he starts with everything in its place. Early works on paper run to quick scratches and stains, in etchings and aquatints that keep everyone at a distance, including him. His 2017 retrospective stressed his debt to Pablo Picasso, and they face off on a single sheet the year of Picasso's death. Still, when Hockney assembles a portrait from multiple photos, he displays not so much Cubist fragmentation as a delight in images, one after another. When he takes up the pen, he prefers a Rapidograph for its even inking, but surely also for its trademark rapid line. He values Ingres not for the classicism, but for the economy.

Not that he is all that into surface detail, no more than inner truth. He can pull a figure together handsomely from the pattern of a shirt—or a face from little more than eyes. When he shows male joggers, it is a study not in human anatomy but in passing lust. Much else, he learns in time, passes, too. When he turns late in life to watercolor, it is not to miss one inch of the encroaching darkness. He has seen it before with his parents, and he will see it again with his closest friends.

As curators, Sarah Howgate of London's National Portrait Gallery and Isabelle Dervaux pick just five portrait subjects, counting Hockney himself. Not that he follows any of them the whole time, and the gaps are as telling as the images. He first depicts his mother at over sixty, looking forever young. She ages fast, though, and Hockney uses greater detail to capture the physical and emotional cost. He loses track of other sitters for decades at a time, which only heightens the shock when they return. He has a different relationship with each one.

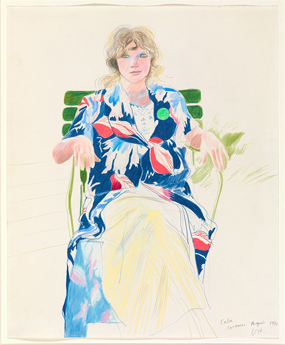

Celia Birtwell starts young and attractive, and she remains nothing less than composed. A designer who costumed the Beatles and the Stones, she gets to wear fuller fabric than Hockney often permits, with the added allure of his rapid notation. Gregory Evans, a curator and lover, stays young even longer, because neither party can let go. When he looks off while sitting in a comfortable chair, it is hard to know whether they are intimate or mutually withdrawn. Hockney first collaborated with Maurice Payne, a printer, on the poems of C. P. Cavafy, and Payne is always the serious one, no matter how much they try to lighten up. Just as poignant, there are limits to what the artist can know of them all.

Is that why so large a show, filling both the Morgan's main galleries, goes so fast? Yet Hockney is well aware of his limits, treasures them in fact, and they become his subject as well. In the one exception to portraits, he illustrates The Rake's Progress, only loosely after William Hogarth. He shows his hero expelled from just the right New York club—for lack not of charm but of cash. In the end, he descends into BEDLAM, a word repeated across the image, and he loves every minute of it. He is making fun of his own shallowness and pleasure, so that he can come to peace with both.

David Hockney ran at The Met through February 25, 2018, and at The Morgan Library through May 30, 2021.