Painting the Death of Painting

John Haberin New York City

Andy Warhol's Last Decade and Early David Salle

I came to New York to look at modern art, only to watch it fall apart. Maybe the shock came when Mary Boone opened her gallery in Soho—or maybe when she first showed David Salle in 1980. Now both are fixtures on classy blocks in Chelsea. A gathering of pictures from the early 1980s, red dots next to each one on the list, stakes its claim to Postmodernism as an art-historical event. It also takes me back to when I first found them annoying, alienating, and intimidating. But if it was a game changer, what exactly had changed?

Andy Warhol could claim to have seen it all twenty years before, but he was asking much the same question. A show of his last works shows an artist in his fifties still changing things. Glib, maddening, and shallow, he was not just toying with found images. He was verging on abstraction and learning to paint again. With images of death, he was wondering if he is dying or if painting is dead. He was also, almost despite himself, helping it survive.

Dead last

Something funny happened to Andy Warhol, but what? Did he simply lose it, or was he glib all along? Was he still Warhol as illustrator for books and commerce? Or was Andy Warhol always deadly serious, never more so than in a nervous last decade? He even cast aside his head for a television appearance on Saturday Night Live.

When The Brooklyn Museum calls it arguably his "most productive" period, it has a point—in the economic sense, of turning out a product. The sheer volume of his work increased in the years before his death in 1987, at just fifty-eight years old. Any gallery-goer knows its numbing ubiquity. Already work from the 1970s, like the Warhol Polaroids at the Nasher Museum last winter, stood one step above Gap ads. Try not to notice that "The Last Decade" shares a museum with a survey of high fashion. Try not to notice that it includes a filmed interview with Diana Vreeland.

Andy Warhol continues to shock all the same. Nothing in "Haunted," at the Guggenheim, is as haunting as Orange Disaster from 1963. Of course, the earlier Brillo box startled Arthur C. Danto into a philosophy of art. And his films of the 1960s still feel dark, static, frank, and erotic. Nothing packed as much of a punch this year in "1969," at P.S. 1. Warhol's motion pictures, especially Empire, may have had their roots in William Klein and Broadway by Night, they have inspired video by Douglas Gordon, and I still see them whenever I look at the Empire State Building at night.

Even in 1978, opening that last decade, the Shadows cast a shadow. They stopped me in my tracks at Dia:Beacon, where more than a hundred line a room, each a stiff sign of absence draped across a wall and floor. Brooklyn has just four of the paintings, along with two more in an eerie mix of silkscreen and glitter. The same room has a black Marilyn, and a ghostly white Mona Lisa. It also has the Oxidation Paintings in acrylic, metallic paint, and piss. They look random and ugly, and they echo the iconic texture and scale of Jackson Pollock anyway.

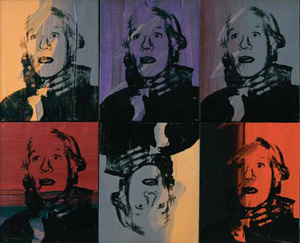

As so often, Warhol sneers at art and honors it. He degrades himself, but with a sad and cunning awareness of his self-degradation—as in his Strangulation self-portraits the very same year. One can laugh at the multiplied images of a hand around his neck, but the grip still tightens. He seems to have a new sense of mortality, though death obviously runs through the early car crashes and electric chairs as well. Besides, he had faced an assassination attempt in 1968, the subject of "I Shot Andy Warhol," and it had only made him back off experiment. Then again, he had already sworn off painting for film in 1965.

Andy Warhol has multiple excuses for everything, not unlike the floundering Brooklyn Museum. The museum has him on camera for his own TV show—perfectly open and unrevealing, even to himself. He sounds naive, blank, and sympathetic while questioning Larry Rivers on the latter's sex life. Somehow, though, he felt a need to make painting count after so many society portraits and dollar signs. He had to try abstraction, and he had to confront death with his own "sinister Pop." Did I mention that his last big work was The Last Supper?

After Shocks

And yet he had to churn things out, too. "The Last Decade" opens with bland self-portraits as wallpaper. No wonder a Self-Portrait (Strangulation), mounted on top, stands out. The Last Supper came with funding from a bank in Milan, and he stencils a bargain-basement price tag on one version. He tries abstraction again with the Rorschach paintings, on his largest scale yet. They keep hammering at the puzzle of greatness and anonymity, but with the emphasis on the anonymity.

Perhaps one can prove anything by careful selection. A show last year of Picasso's last decade deserved its crowds and raves, even if no one painting did. Still, late Picasso looked as drab as ever shortly before at Yale, and a packed final room looks even worse at the Met now, in a show of its own holdings. But one knows that, too, from the prints in pretty much any uptown gallery any day of the year. Like Picasso, Warhol knew that he could please and had changed art, and he could never stop trying to please or to experiment. The Factory always meant too many parties and collaborations, but also a real challenge to the "originality of the avant-garde."

Warhol could resist anything except temptation. After the shocks of 1978, he is on to his two attempts at a TV series, anticipating reality TV today. He is assisting Jean-Michel Basquiat, supplying logos and stenciled letters for Basquiat's skulls and splatters. He credits Basquiat with making him paint the old-fashioned way, but he also must have loved having another heir and acolyte. He is churning out covers and interviews for Interview magazine. All-over abstraction quickly veers into blander, colorful Thread paintings—on commission from a fabric company.

Is there a secret to growing old? The art market demands an old master, as with Rembrandt or Pablo Picasso, and sometimes it gets one. It may help to have enough success to gain wealth, confidence, and independence, but not too much. Without the first, one may stop advancing or give up entirely, and with the second one may drown in celebrity. Late Monet had near blindness and self-enforced isolation, while Robert Rauschenberg and Roy Lichtenstein grew almost as glib as Warhol. Then again, this kind of theory reinforces the avant-garde myths that obsessed them all.

One can make too much of Warhol as an individual. The Brooklyn Museum sure does, with a small show, broken over two floors, on an overly familiar decade. Probably the museum longed for another chance to tout Basquiat, as part of what it deems community outreach. Artists who love to hate Modernism or Postmodernism make too much of Warhol, too. Rauschenberg did more to introduce appropriation, and Minimalism did more to combine industrial materials with art as installation. The ease of silkscreens and party-going, though, makes him an easier target.

Warhol knew that, too, and it has so much to do with his last decade. He is wondering about art after conceptual art and wondering if he or anyone else should be painting. He is wondering if someone like Basquiat is the future. In fact, he is confronting the same issues as much younger artists at the very same time. David Salle, Eric Fischl, Paul McMahon, Matt Mullican, and others were trying both to paint and to defy painting. That is why they often draw on Warhol—and why a clumsy, pandering, embarrassing exhibition is still spooky and relevant.

Bright lights, big city

No doubt Modernism was falling apart from the moment it began, like the space of Cubism. And no doubt every generation since had its own near-death experience, like the turn in mid-century from Paris to America—or, later, from painting to silkscreen and Minimalism. Still, something confronted me head-on in 1980, not to mention my friends who just wanted to paint, and it was not a pretty sight. Soho in particular had seen a wave of Neo-Expressionism, like Georg Baselitz and Julian Schnabel, followed quickly by the critical irony of Barbara Kruger and others. People lined up to take sides, but what side was Salle on? Part of what made him so disturbing was having to ask.

That show at Mary Boone set David Salle alongside Schnabel and Ross Bleckner. He also played bright lights, big city to Eric Fischl's suburbia, which some like to call expressionist. Both let young men into the room with steamy sex, and if anything Salle shows more chops as a realist. He often models a nude against a single color, in a style like black chalk, then overlays the outline of someone else, like a quick pen drawing but in oil. Still, no one will mistake him for a savior of good old-fashioned painting. The classic assault on Neo-Expressionism by Hal Foster, as self-indulgent individualism, hardly applies to Salle's impersonal chill.

That show at Mary Boone set David Salle alongside Schnabel and Ross Bleckner. He also played bright lights, big city to Eric Fischl's suburbia, which some like to call expressionist. Both let young men into the room with steamy sex, and if anything Salle shows more chops as a realist. He often models a nude against a single color, in a style like black chalk, then overlays the outline of someone else, like a quick pen drawing but in oil. Still, no one will mistake him for a savior of good old-fashioned painting. The classic assault on Neo-Expressionism by Hal Foster, as self-indulgent individualism, hardly applies to Salle's impersonal chill.

Boone also exhibited Kruger in the 1980s, and the Met included them both in the "Pictures generation." Salle shares the group's irony and detachment, with appropriation so aggressive that one wants to shout theft. Text and color fields alike collide with representation, and an actual shelf or table may stand in front. Sources include magazines, porn, and Old Masters, but rarely Modernism itself. At the same time, politics has taken a holiday. If Jenny Holzer or Cindy Sherman are confronting the all-seeing male eye, Salle is public enemy number 1.

That holiday, too, contributes to Salle's chill. It helps explain why he still makes me uncomfortable, but now in a good way—and why his show is at once part of my distant past and very contemporary. He was the bad boy before his time, the guy who called a painting at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Good Bye D and made you think of the D as a hired killer's signature. I remember how John Ashbery's poetry confused me, too, with disjunctions that I could not tease out the way allusions fill in the gaps in The Waste Land. However, Ashbery belongs to an earlier time, like Rauschenberg, and his jump cuts have Rauschenberg's casual but trenchant wit. With Salle, any hint of optimism is gone, as if the parts of a combine painting could never again combine.

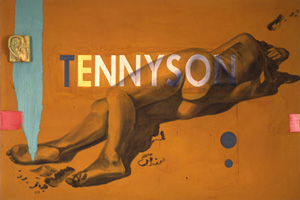

With Salle, signs of innocence or authority often come last, as the sketchy top layer. They might be TENNYSON, in big block letters, or the outline of a boy's or woman's face out of Georges Seurat or French Romanticism. One looks through them to the porn, as if forced to see through the veneer of civilization. With the collage and colored planes, one might be seeing through Modernism as well. Donald Duck as a seedy man with a cigarette, maybe at a bar or craps table, seems less a parody than a demand. Did you think the artist was any better, and did you think you were?

Street art, even Basquiat's knowing version, kept the attitude but turned up the heat. The view from Soho was too narrow anyway. With the Times Square Show of 1980, including Holzer but also Kiki Smith, art was recovering the human body as more than formalism and more than the male gaze, and do not even ask about Europe. Besides, Postmodernism needed Modernism to keep itself alive. And there, too, Salle's history seems newly relevant. Given the stale aftertaste of Damien Hirst at Gagosian or Jeff Koons at the New Museum, could the whole battle over male gestures be old news at last?

"Andy Warhol: The Last Decade" ran at The Brooklyn Museum through September 12, 2010, David Salle at Mary Boone through June 26. The review of Salle first appeared on Salon Dagmara, edited by Claudia Schwalb.