Exile at Home

John Haberin New York City

R. B. Kitaj and Stéphane Mandelbaum

R. B. Kitaj ended his career in LA. If you think of him as an English artist, you might imagine him in exile.

Did you know, though, that he was born in the United States? Kitaj could be at home or in exile on both continents. The School of London will not go down in history for its sense of humor. Yet the man who gave the school its name could still laugh at art and himself. Across the Channel and the North Sea, Stéphane Mandelbaum might have been a face painter, too, an ugly and shocking one, if only he could hold his line in check long enough to paint. He died at just twenty-five, in 1986, of a hit job. Yet his life was only as messy as his art.

Punching back

Beginning with Francis Bacon, English artists seemed to compete to express horror and revulsion—and to inspire horror and revulsion in others. The very subjects of Bacon's best-known paintings, the Crucifixion and Pope Innocent X, attest that this is no laughing matter. R. B. Kitaj knew high seriousness when he wished, but he did not always take it so seriously. His version of a dead Christ lies in what could pass for a fish tank, like a beached whale, and it is only Pretending to Be Dead. He rendered an earlier artistic rivalry, between James McNeil Whistler and John Ruskin, as a boxing match. In self-portraits he appears as a terrorist, a woman, a black sheep, and a punching bag.

In ordinary neurosis, self-flagellation is a serious matter, and Kitaj kept at it. He became The First Terrorist in 1957, six years before his first exhibition, and a punching bag in 2004, three years before his death. The boxing match, too, aspires to a place in art history. It may joke about the libel suit against Ruskin, the critic who accused Whistler of "flinging a pot of paint in the public's face." Yet it places Kitaj in their august line, and it borrows its composition from a rather earnest American painter, George Bellows. Even when he is punching himself, this artist is punching back.

All four paintings appear in a healthy selection of his work, curated by Barry Schwabsky. It follows Kitaj to his late years in LA, as "The Exile at Home." Few artists seem anywhere near as English, but he was born in Ohio, as Ronald Brooks, and he took his name not from British colonialism in India, but from his Austrian stepfather. (Try not to pronounce it kitsch.) For him, art is always in exile, and he coined the term diasporism to describe it. He knew that Whistler, too, thrived as an American in London.

The school had its roots anywhere but at home. Bacon was born in Ireland, Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach in Berlin. Leon Kossoff was the child of Russian Jews, like Kitaj's mother. Their exile may appear in Bacon's agonies, Freud's distorted portraits, Kossoff's repeated self-portraits, and Auerbach's darkly slathered paint. Kitaj evokes displacement with the urban idlers in Arcades, after the studies of Paris by Walter Benjamin, and with Franz Kafka as only a hat. Another self-portrait calls him The Jewish Rider, punning on Rembrandt's The Polish Rider, a notoriously strange figure in a distant landscape.

All this sounds solemn enough, but Kitaj's colors keep getting brighter and his backgrounds more filled with white. Schwabsky compares them to Henri Matisse and Paul Cézanne, but they approach Modernism from the perspective of a good illustrator. A black outline here and there may recall Max Beckmann, and a schematic face has the flair of Alexej Jawlensky, but their Expressionism seems long ago and far away. Kitaj comes closest to another exile in LA, David Hockney, whom he knew from their years at the Royal College of Art in London. They share an obvious facility that crosses over into Hollywood glibness. He was not altogether joking when he called the show's last painting his Technicolor Self-Portrait.

A joke can serve as a defense mechanism as well. When he titles a woman with big boobs The Sexist, it sounds like special pleading. He is at his best when humor gets along with a deeper mystery. In I Married an Angel, the angel has wings and approaches his bedside— with the choice between consummation and salvation still to come. A nonpracticing Jew, he found in religion, too, a deeper mystery. I laughed at The Jewish Rider, but Rembrandt, the painter of The Jewish Bride, would have approved.

Too many suspects

If a retrospective for Stéphane Mandelbaum were a crime novel, there would be all too many suspects. The curators at the Drawing Center, Laura Hoptman and Susanne Pfeffer, speak discretely of a criminal syndicate, but he himself barely skirted the law. He trafficked in the black market for art and got caught trying to steal a work by Alberto Giacometti. He hung out in all the wrong places, only starting with clubs and cafés in Brussels.  The dark night scene in Montmartre for Pablo Picasso seems tame by comparison. His drawings themselves bear damaging testimony.

The dark night scene in Montmartre for Pablo Picasso seems tame by comparison. His drawings themselves bear damaging testimony.

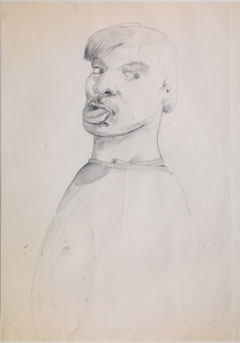

They start with fellow denizens of that scene, with unfailing sympathy. It extends to young white men and black women in racially charged surroundings. Titles identify them by first name, because his art was on a first-name basis with everyone. He calls them collectively Lolitas, with the humor turned at least partly on himself. His pencil swoops casually across the page, staking out faces and poses alike in its long traces. He works fast, and there is no going back.

Mandelbaum drew what haunted him. That, at least, is a given for a compulsive artist, but it raises more questions than it answers. He drew what he loved, in faces out of his favorite haunts and dearest imagination. He drew, too, what he hated and feared. But which was which? What were his nightmares, and what were his dreams? An artist who blended self-portraits with Nazi imagery may not himself have known.

Who can say what he left to his fevered imagination? Raised as a Jew, Mandelbaum heard of the Holocaust from a grandfather who survived it in Poland and whose brothers did not. A book, a gift from his father, helped him follow that family history, but in reverse, like a personal journey into the past. Its title says it all—Souvenirs Obscurs d'un Juif Polonais Né en France, or "Dim Memories of a Polish Jew Born in France." A series of drawings takes off from the book, by Pierre Goldman, but with embellishments. He cannot disentangle observation from confession and confessions from nightmares.

He draws Nazis like Ernst Rohm and Joseph Goebbels, the latter in the midst of a terrifying speech that Mandelbaum could never have heard. He draws the filmmakers he admired most, including those he could never have met. Naturally they, too, made their name with subject matter on the edge, like Pier Paolo Pasolino, Luis Buñuel, and Rainer Werner Fassbinder. He draws Arthur Rimbaud, the poet, dressed for a rendezvous in cold weather. He sketches Francis Bacon, whose insistence on finding character in the cut of a face anticipates his own. He leaves open, though, what counts as realism and what as distortion, as Bacon never could.

A solo show extends from the main gallery to the smaller one behind it, and the ample space only raises more questions. Just what kind of artist was he—an outsider before outsider art entered the mainstream, the graduate of a proper arts education, or a willful heir to Bacon? After the café drawings, he crowds more and more onto a sheet. That includes text fragments that are all but illegible, collage like the face of a Nazi on a porn star, a self-portrait as Geule Casée (or "Broken Face," only more vulgar in French) and swarms of pen marks like armies on the march. He may never earn a greater reputation outside Belgium, but he provides testimony to a fatefully short life. The real killer may have been the twentieth century.

R. B. Kitaj ran at Marlborough Contemporary through April 8, 2017, with prints at Marlborough uptown through April 1. Stéphane Mandelbaum ran at the Drawing Center through February 18, 2024.