Birthing Feminism

John Haberin New York City

Judy Chicago and Shahzia Sikander

Judy Chicago ends her retrospective with other women. It could hardly be otherwise, when her best-known work, The Dinner Party, relied on the assistance of four hundred. With its place settings for thirty-nine more, it sought to span recorded history as well.

No surprise, then, if she devotes a full floor of her retrospective to women across the centuries and across the arts, at the New Museum. It could hardly be otherwise, when she titles it "Herstory." For her, a women's history is not just recovered but created again each time, and so is art—not as a male saga of lone genius, but as a collaboration. She reserves a place for goddesses as well as humans as well. She keeps coming back, too, to acts of birth. Will women still recognize it as their own?

I have my doubts. New York was not new to her in 1980, when The Dinner Party reached the Brooklyn Museum. (It later found a permanent home at the museum, as anchor to its Sackler Center for Feminist Art.) She and her first husband had hitchhiked to New York in the 1960s, living briefly in Greenwich Village. Still, she felt new to New York. She left a personal stamp on feminism, one that not everyone could accept but many have loved—one rooted in primordial beings and present-day sex organs.

I have my qualms about questioning her. It aligns me with conservative critics like Hilton Kramer of The New York Times, who trashed her back then along with pretty much all postwar American art. It puts me, a white male, in the position of speaking for feminism when I hope to support it. And her retrospective does offer a greater diversity, including the glassware, ceramics, and embroidery of those place settings. She deserves credit, too, for founding the Feminist Art Project at Cal State Fresno and later, with Miriam Schapiro, at Cal Arts. Still, whatever her history or herstory, she is always at its center.

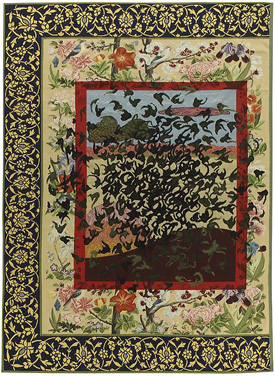

Shahzia Sikander is laying down the law. If that sounds grim, do not despair. She means it to be as light as air and as natural as breathing. An obvious heir to Chicago's certainty, she means her sculpture to speak for a Pakistani immigrant and for women everywhere. If that sounds a little grim anyway for public sculpture, this is feel-good art—and that may be the grimmest prospect of all. Madison Square art has never looked so well-meaning or so empty.

What if?

Banners hang over The City of Women, that floor-scale installation, with one in particular flying high, What If Women Ruled the World? And here they do rule, but at a cost. You will spot paintings by Hilma af Klint, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, and Georgia O'Keeffe, amid less-compelling models for Symbolism and Abstraction. You will spot those who refuse to be reduced to "significant others," like Dora Maar (for Pablo Picasso), Frida Kahlo (for Diego Rivera), Leonora Carrington (for Max Ernst). You will spot Käthe Kollwitz next to Martha Graham, with an eye to how women pose, and painters near books and photographs of writers, with labels you may never find. For all its wonders, it eradicates differences and reduces everyone.

Chicago began as an exemplar of California Minimalism. Born, of course, in Chicago (adopting her last name to define herself as no one else's), she studied at UCLA. She enrolled in auto-body school and spray-painted hoods, another assault on gender roles, but it, too, seems right for automobile territory. She also titled her day-glo versions of Light and Space" after birthing and body parts. The Dinner Party takes the shape of a triangle at that. A woman may be capable of anything, but she might as well quit, from the sound of it, after becoming a mother.

Even so, Chicago keeps demanding more. She took the Feminist Art Project seriously. Her classes became Womanhouse—collaborations with her chosen students, with their everyday lives as performance art, and she credits the resulting film and photographs to them and not to herself. She does not abandon spray paint and lacquer, now on vinyl on canvas. Still, in adopting a radial motif and at times ceramics, she is well on her way to the strengths and weaknesses of The Dinner Party. I may not like it, but it anchors the Sackler Center and the feminist revolution to this day.

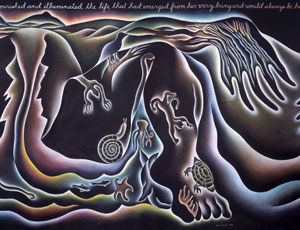

Embroidery and collaboration carry over to the Birth Project of the early 1980s, with at least one hundred fifty women to execute the needlepoint. Colors darken, but not for long. Men get their project, too, but with articulated musculature and grimaces that had me grimacing as well. Still, she adopts the translucency of stained glass for her Rainbow Shabbat of 1992. She also collaborates with her present husband, Donald Woodman, on a larger Holocaust project and, in New Mexico, a co-ed follow-up to Womanhouse. Women's roles have become gender roles in a racially torn America.

As curators, Massimiliano Gioni, Gary Carrion-Murayari, Berkeley's Margot Norton, and Madeline Weisburg proceed in series, because her chronology unfolds that way. They barely touch on projects that I have mentioned from the new century. Still, no question but her productivity has fallen off herself. They also give her earliest work more than usual space, which explains a great deal, while not trying to reproduce The Dinner Party. In one early series, she stands amid fires and smoke. For once, a woman's body spreads and consumes its traces.

Chicago gets all three principal floors, including the last for her city of art and women. If you happen to begin there, so much the better. It makes clear how much her hopes do not depend on birthing. She herself never bothered with motherhood. As she told The Guardian, "There was no way on this earth I could have had children and the career I've had." Her work is still tacky, sentimental, and reductive, but she gave it her all.

Laying down the law

Sculpture is not exactly laying down the law on Madison Square Park or on art. The New York State appellate courthouse stands just across Madison Avenue, facing only a side street. You might never notice the statues overhead of such certified law-givers as Moses, Confucius, and Justinian. (Muhammad had a spot, too, until people objected, as racists do.) Shahzia Sikander, who in the past has showed her fine command of Asian and Islamic art, adds the first woman to their company, at the eastern end of their row. If that makes her sculpture closer to the dawn, it is NOW, as in the "fierce urgency of now."

The gilded nude faces head-on, with a full body and impassive smile, more a goddess than a historical figure. Her stone brethren look downright human by comparison. Her one point of reference is a frilly collar, the kind in formal portraits of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. But then people can buy their own copies of her collar, available online (although not from Sikander). Just to think of the notorious RBG should make you feel good, right? If not, descend to the far side of the park for Witness, a figure closer to the earth and sky.

I cannot swear that this gilded nude is larger, although I think so, but she seems all the more towering close up and face to face. At the very least, she is broader, with a gilded cage spreading out from her waist like a regal dress. She has also acquired arms and legs—or rather their twisted remains. They are roots, Sikander explains, and she is "self-rooted." She must be, for she is the very mother of us all, Havah, the Hebrew or Arabic version of Eve. Who knew, but she is also Urdu for atmosphere or air, in a show subtitled "to Breathe, Air, Life."

I cannot swear that this gilded nude is larger, although I think so, but she seems all the more towering close up and face to face. At the very least, she is broader, with a gilded cage spreading out from her waist like a regal dress. She has also acquired arms and legs—or rather their twisted remains. They are roots, Sikander explains, and she is "self-rooted." She must be, for she is the very mother of us all, Havah, the Hebrew or Arabic version of Eve. Who knew, but she is also Urdu for atmosphere or air, in a show subtitled "to Breathe, Air, Life."

Her hoop skirt bears not fabric, but decorative mosaic curves. They go well enough with the installation's last component, Apparition. Aim your cell phone at a QR code and spots of color dance about the nudes. The image may not count as augmented reality, but then everything here claims that august label. If you cannot ascend to a higher reality, shape up. The law is the law.

Still not feeling good about yourself? You had your chance in 1989, when a bronze bull descended on Wall Street, in celebration of America's energy, wealth, and greed. You had it again in 2017, when a little girl first faced it down, delighting no end of tourists—or when Simone Leigh rested a black girl atop the High Line. Now Hew Locke brings his own gilding to global traditions at the Met. Gilt fills the long-empty sculptural niches along Fifth Avenue, following Wangechi Mutu and Carol Bove. Urns and shards of urns from any number of museum collections have acquired eyes.

Maybe public sculpture has always felt the pressure to make people feel good, but feel-good sculpture has a new urgency in markets and museums today. Not just Wall Street is big money. I cannot call Locke's sculpture pandering, no more than any of these works, not when the artists are so evidently sincere, but it is tacky all the same. (Why not just seek out the originals at the Met—or the black potters of Stone Bluff Manufactory this past winter?) The trouble set in not with Eve, but with Chicago, who opened her late 1970s feminist history with gold chalices and goddesses. If you ask me, art and activism need not more primordial women, but fewer male gods.

Judy Chicago ran at the New Museum through March 3, 2024. Shahzia Sikander ran in Madison Square Park through June 4, 2023, Hew Locke at The Metropolitan Museum of Artthrough May 22.