The Other Woman

John Haberin New York City

Miriam Schapiro, Judy Rifka, and Mary Bauermeister

Critics demanding more women artists in museums might take comfort in Miriam Schapiro at the National Academy Museum. So might "third generation" feminists who would never deign to vote for any woman, rather than the right woman. Schapiro offers both plenty of choices. So does Judy Rifka, whose dedication to abstract painting rests on eclecticism and a very urban sensibility. Whoever you have in mind, she, too, is always the other woman.

Such is often the fate of women artists, older artists, or artists like her who reinvent themselves again and again. That fate can befall the steadier output of Mary Bauermeister as well, with art that may seem to belong to the past but that claims to encompass an "omniverse." The market is now looking desperately for rediscoveries, to stay one step ahead of the game.  Still, even that leaves others in the dust, and it shifts the focus from the work to the name. What exactly where they doing all along? Take a well-earned look.

Still, even that leaves others in the dust, and it shifts the focus from the work to the name. What exactly where they doing all along? Take a well-earned look.

The lives she led

Miriam Schapiro showed with Abstract Expressionists in the 1950s and in "Toward a New Abstraction" at the Jewish Museum in 1963, and she shared a gallery with another leading woman artist, Helen Frankenthaler. She could paint big with the best of them, in canvases as tall as wide, with big strokes and bright colors right out of Willem de Kooning. She painted hard-edged abstraction in the 1960s, with some of very first examples of computer-assisted design in painting. She was an exponent of Pattern and Decoration in the 1970s, like Hilary Pecis in California, with dense and often floral designs, quietly shimmering colors, and an early introduction of craft as art and fabric into art. Painting could begin or end as fans, kimonos, or a priestly vestiture. She turned to representation, too, well before her death in 2015, at age ninety-one.

The abstractions alone could come from several different painters. A smaller gallery show of her California years takes her from big, bold geometric shapes, bursting into a fictive third dimension, to the patterns, with giant steps along the way. They run from 1967 to 1975—and from metallic paint to spray paint and Mylar. Computer designs pushed her toward illusion, in short lines against monochrome backgrounds that assemble into cubes on edge. They also pushed her toward collaboration, with programmers at the University of California, San Diego, back when no one had a laptop and Photoshop. And that show skips right over Schapiro's crucial collaboration, with Judy Chicago at CalArts, where they founded the Feminist Art Program in 1971. Their Womanhouse in a decrepit Hollywood mansion became a gathering point, an almost scandalous exhibition space, and a workplace for nearly two dozen others.

Her many styles could stand for the lives she led—the girl born in Toronto, the kid growing up in Flatbush, the art student in the Midwest, the Jew who worked Hebrew letters and the word Juif into a painting of My History, and the woman who returned east to the quiet of Long Island. They could also be one reason for her relative lack of prominence, even as so many know her work and her name. For an artist, it can help to delve into something for a long time, to acquire not just its scope, but also a brand name. Does anything hold those lives together, besides the sheer delight in reinvention? The museum sees first and foremost "a visionary." Yet continuity emerges, too, in her successive reflections on her art and herself.

The visionary appears in Vestiture, but also in Agony in the Garden, a self-portrait pierced by more nails than Jesus ever knew. It connects her to folk art, outsider art, and Art Brut, as do her fabrics. Not your everyday mystic, her quite worldly visions also include her Shrines, geometric abstraction laid out as grids with the illusion of beveled frames. Sixteen Windows looks out onto a silver sky, while another shrine pays tribute to her studio, with two tubes of paint. So do works from her P&D years that insert their patterns into off-kilter grids from earlier work—and so does that personal history, with anything she cared to remember.

Most often than not, though, her vision is a feminist one—and not just in what she called her femmages. It appears as early as the flesh tones after de Kooning or her hard-edged Big Ox, with its vaginal O. The curator, Maura Reilly, describes its spaces as labial. Later she borrows her agony from Frida Kahlo and patterns her patterns after Faith Ringgold. Most of all, her contribution to Womanhouse gives women a place and a history. Her three-tiered Dollhouse is a veritable history of confinement, with rooms for a harem as well as a bedroom and kitchen, with men lurking just outside the windows.

Despite the assistance of Sherry Brody, it is also a very personal history. It has her studio, a miniature of Sixteen Windows, hidden treasures, and uppity actors along with its threats. A cat feeds happily with mice at its side, and a snake and a black widow spider could both stand for women disturbing the garden. Is it enough to recover her as an artist? While the retrospective manages her greatest hits, in no particular order, it remains small for so many women. Maybe a larger show will allow them all to make her case. For now, I am betting that it will rest on her patterned paintings.

Layers in motion

Judy Rifka polished off her installation of works past and present by rehanging her latest and close to largest. Collapsing gridded cones and cylinders appear to spiral across a field of pure black. Magnetic fields? A fantasy of computer-assisted design? Nope, just the remembered shapes of things on the street, rendered in paint. In the process, they become layered, transformed, and set in motion.

Rifka insists on layering and motion as a constant in work of more than forty years. It is consistently slippery, between two and three dimensions, subject matter and composition, image and object. If you have an association with the painting, you are likely to be wrong. Perhaps her most spare and painterly bear the title A History of Sculpture. Another painting began as a structural analysis after Leonardo, another resembles a puppet show, and some from the 1970s began as an alphabet, but never mind. These are first and foremost abstractions.

Some of the earliest work incorporates text, but even then as a layer and with reference to performance, like dog show or danceterian. After that, what looks like collage is likely to be the sheer accumulation of acrylic. Individual brushstrokes remain visible in undifferentiated fields of red, black, or white on otherwise unpainted panels.  And what look like accents of color on black prove a variation on collage, but without mixed media. These are circles of canvas, held down on unstretched canvas only by long drips of paint, and some are already starting to peel off.

And what look like accents of color on black prove a variation on collage, but without mixed media. These are circles of canvas, held down on unstretched canvas only by long drips of paint, and some are already starting to peel off.

Of course, motion is not everyone's idea of consistency, and Rifka has started over many a time. Like Frank Stella, she thinks in series, and she has suffered for it. It did not entirely fit with the demand for rigor when she began, and it does not entirely fit in with today's demand for that elusive brand name. She showed at Gracie Mansion, perhaps the epitome of East Village art back then, but more steadily and often at Soho's classier Brooke Alexander. She appeared in a couple of Whitney Biennials in the 1970s and 1980s, but also in a legendary clash of art and counterculture, the 1980 Times Square Show. In between, she never quite got the message that painting is dead, and neither did I.

The curator, Gregory de la Haba, is still making discoveries as he plunges through her archives, and works rotate in and out through the course of the show. Rifka shares The Yard, an office and conference center, with Jay Milder. Born in 1934, Milder has been very much consistent in style, but just as much out of the public eye. He uses thicker brushstrokes against black, like Abstract Expressionism as street art after Jean-Michel Basquiat. The space turns out to work splendidly for art, even with a pile of pizza boxes from the previous day's conferencing, with both quiet alcoves and long vistas. It allows Rifka's series to hang largely apart.

Like most painters willing to take chances, she has had her share of false starts. I first met her holding a cuddly 3D painting, from the series In the Round, like the world's largest and airiest paperweight, and others not in the show can be too busy. The series soar when they achieve a logic and focus of their own. In earlier work on both canvas and cut paper, fields of gray verge on tan and tan on gray. More recently, the colored circles nestle amid silvery white traces, like particle tracks or macromolecules, but then (oops) I said to forget the associations. Stick to their lean motion against uninterrupted black.

Dead, serious art

Much of the pleasure of Joseph Cornell boxes is that they may contain anything. Much of the terror of boxes for Kurt Schwitters is that they may as well. Not everything from Mary Bauermeister fits into a shallow wood box under glass. Some of her finest displays of wood, stones, and words spill out onto the wall, as if driven by their own radiant energy. Yet the principal thrust of her "Omniverse" is within, with an implicit demand on viewers to look within themselves as well. And that thrust allows them to grow into pleasure or terror the closer they get.

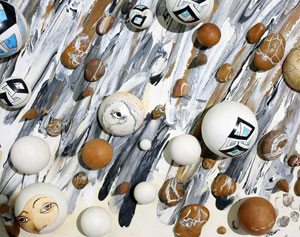

Like the perfect hybrid of Cornell and Schwitters, Bauermeister may seem a leftover from Dada or an embodiment of outsider art. She has the casual scrapings of the first and the obsessive repetition of the second, while lending them both the polish of early European modernism. She covers small spheres with text, squiggles, faces, and polished surfaces. She layers stone upon stone in regular circles, preferring sea stones for their weathered smoothness. Like a hybrid of the older artists, too, she worked between Europe and America, starting with an exhibit at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1962, while still in her twenties, and her first New York show on 57th Street in 1964. Yet she came to the city to get in on the late modern action.

She would have known the drive here toward appropriation in Robert Rauschenberg and toward regular geometry in Minimalism. She identified most, though, with Fluxus, for its playfulness and multimedia. There she found what the show calls her "Omniverse," at once all-encompassing and impatient with claims to wholeness or unity. There, too, she looks both outward and within. She displayed her early Sand-Stein-Kugelgruppe (or "sand, stone, sphere group") with music by Karlheinz Stockhausen, with whom she studied and whom she briefly married. They divorced in 1972, the year she left for Germany, never to exhibit here again.

Unlike Cornell, she shuns allusion to art history, but with no shortage of reflections on art. Unlike Schwitters, she stands apart from the brutality of war, but with another sort of anxiety. Her wood cylinders tapering to a point could be undersized spears or oversized colored pencils, and some come with the label pen. Another work announces that My Contribution to Light Art Is Dead, Serious Art. Apparently she will not follow Pop Art in accommodating art to anything less than itself, and apparently serious art requires irony or a joke. The comma before serious leaves open whether art for her is dead or English too great an obstacle to expression.

The show sticks to her New York years, pretty much because it has to. Back in Germany, she became wrapped up in "geomancy," while finding a clientele for garden designs instead. Maybe she knew that Cornell had tapered off, too, almost as soon as he found a wider audience in the 1940s. He had also become an adherent of Christian Science and Mary Baker Eddy. Maybe, too, her years of extroversion and collaboration could extend only so far. The work has plenty to say, but only if one looks within.

Just in case one is not looking closely enough, Bauermeister tops many compositions with lenses. They do not so much focus the eye as draw it every which way. The lenses are rarely convergent, and a box has way too many anyway for a single point of view. They show the carvings like pencils tapering into concentric circles of bright color, almost the only color apart from shades of gray stone. Text competes with squiggles to describe the art itself as affirming or anxious—a matter in French of yes or night. Step back, though, and Bauermeister is composing something like paintings, with all the distortions, geometries, and diversity of her omniverse.

Miriam Schapiro ran at the National Academy Museum through May 8, 2016, and at Eric Firestone through March 19, Judy Rifka and Jay Milder at The Yard under the auspices of Amstel Gallery through December, and Mary Bauermeister at Pavel Zoubok through May 21.