The Illusion of Minimalism

John Haberin New York City

James Turrell

"You can't carve it or chip it away." James Turrell was talking about light—and the challenge of working with it to create something so clear, so precise, and so seemingly palpable as to approach sculpture in white marble.

He can, though, carve with it, and Turrell had just finished chipping away at a New York institution with an aura of its own. His Guggenheim retrospective holds only five works in light from nearly fifty years. Some may never get past the lobby, for an entirely new work meant to stop you in your tricks. Turrell emerged in the 1960s from a loose movement of Southern California artists known as Light and Space, and for a while a museum has become his source of light and his space. (Who needs that crummy little pool anyway?) He can settle for playing a guru or a showman, but the transformation of objects, architecture, and experience is real.

In fact, a wedge of light by Turrell has at least two aspects. It exists as an heir to painting and as Minimalist sculpture—both in their most grandiose mode. One can see it as the two sides of the art object in late Modernism. Call that object the truth in painting. Call it a sculpture, whether created or recovered from everyday life. Either way, it unites volume and the picture plane, and it offers a space for contemplation and delight.

Turrell does something else as well: he plays the illusionist, like Anne Katrine Senstad in neon. And again he engages Minimalism on his own terms. He has long aligned illusion with his sculptural side, in floating masses of light. He reverses one's associations of painting with illusion and Minimalism with the literal. For all his interest in Romanticism and Modernism, he belongs most of all to Postmodernism's theater.

Chipping away at light

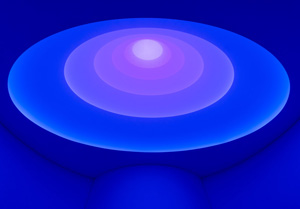

Aten Reign narrows the Guggenheim Museum atrium to a meeting place for people and light. It looks familiar enough, but it has an intimacy and a regular geometry one never noticed before—because Frank Lloyd Wright would not have dreamed of them. Look up, and the building's six levels have become six concentric windows awash with color, ascending to the actual skylight and to white. One might head off for the rest of the exhibition, content with shades of green, only to return to discover a deep lavender. One can also sit for about an hour, as the work completes its cycle. Others may prefer to stand, the better to find common ground.

One can see the work as a summing up. It is site specific, like Meeting from 1986, an office lobby on 42nd Street, and much else in his career. It uses natural light from above, much as Meeting, his permanent installation at MoMA PS1, opens to the winter sky at dusk. Yet it also makes use of LEDs, like the Roden Crater Project near Flagstaff—a work in progress since 1979 and documented in models in a New York gallery in 2009. Aten Reign needs a computer to control them, and as usual Turrell's crew kept tweaking the results down to the wire. Carving in light has to respond to a specific time and place, but this artist does not surrender to the elements.

Aten Reign creates an illusion of mass and volume in those concentric disks far overhead, much like the illusion of a wall at the Whitney Museum in 1980. A few leaned against it and fell, and two sued for damages. (One asked for a quarter million for a sprained wrist, but welcome to New York.) Yet it also suggests a passage into the light, like the stairs leading to his 1992 Irish Sky Garden. A 2006 film about Turrell was titled Passageways. If that also suggests such weightier matters as rites of passage and stages of consciousness, he throws around words like revelation, koan, a primal connection to light, and of course Aten (the Egyptian sun god) the way other artists fling paint.

The same elements combine and recombine in the High Gallery and in two tower galleries upstairs. Afrum I (White) and Prado (White) from 1967 return to the style's origins, in the space of an abandoned hotel in San Diego. The first is a cube suspended in a corner, the second a window by the floor—or so it seems, for both are projected light. Iltar from 1976 is an apparent gray slab on the wall, in reality lit from behind and textured by ambient light. Ronin from 1978 cuts right into the wall from floor to ceiling, lit from within. The thirteen aquatints in First Light, part of a series of twenty from 1989 and 1990, capture these and other shapes as the illusion of illusions.

They are part of a retrospective of sorts, divided among the Guggenheim, LACMA, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. One would have to cross the United States to see it all, and much else cannot travel to any of the three museums. (One can download a multimedia app, thanks to the Guggenheim's curators, Carmen Giménez, Stephen and Nan Swid, and Nat Trotman.) Wondering whether tourists would line up for the Guggenheim to see absolutely nothing? Now they practically can. Its ramps, under ordinary lighting and temporarily devoid of art, might as well be part of the show.

It is a curious retrospective, both small in its selections and sweeping in its geography, but then Turrell at age seventy is not shy about his demands. His body of work comes with its own nebulous vocabulary—of sky spaces, skylight spaces, space division constructions, and ganzfields. He speaks of not representing light, like artists from John Constable to Ad Reinhardt, but presenting it, like Jan Tichy in photogravures and installations, and never mind that the presentation is also an image. He speaks of greeting the light and bringing the sky to earth. When the roof opens at PS1, it reminds him of the Quaker meeting house of his childhood. In the Guggenheim's basement theater, so packed with the press alone that stragglers like me had to watch his image piped into the room next door, his scraggly white beard gave him that much more the air of a prophet.

The shape of light

Then again, his soft voice and gentle humor are real and unforced. When he speaks of Constable and Reinhardt (whom Turrell has curated), he is speaking of artists who moved him. For such a control freak, even Aten Reign is also a letting go. One sits patiently in the cold at PS1, for a work open only when museum hours encompass twilight. Here the crowds come and go at all seasons. This is, after all, a museum lobby. The scrim that creates the narrowed atrium follows and defers to Wright's ramp exactly.

Long lines for empty spectacle have become the norm in an overblown art scene, as with Rain Room at MoMA. Here one sees simple gestures and serious ambitions. The floating cube is as commonplace as the Necker cube, the optical illusion that seems at once to come forward and to recede. The ordinary lights along the empty ramp put things in perspective as well—and maybe take the work down a peg. Besides, buying an extinct volcano in Arizona is no crazier than other earthworks, the mythmaking no more self-indulgent than much else in LA art, the light no more evanescent than for fellow experimenters like Robert Irwin and Doug Wheeler, and the LEDs no less material and no more theatrical than Minimalism. Turrell just has his own versions and inversions of Minimalism's objects and theater.

I could try to convince you that Turrell is still a Minimalist after all, just as for Doug Wheeler in his own California light. You might even believe me, but it also has little to do with why people flock to his work—or so you might think. Surely they go for the wow factor. They go for the illusion. Do his fields of color really have anything at all in common with early color-field painting, like that of David Novros? Is what you see really what you get?

Consider, though, what Turrell had to do with Minimalism in the first place. I mean aside from his age and his interest in earthworks out west, like Roden Crater in Arizona. He long made the visitor's presence part of the theater, as on sunsets at PS1. One shivers with the winter chill as a rectangle cut in the ceiling becomes a cloud of light. He also calls attention to the spaces of a gallery, from little more than readymade materials. Carl Andre does the same with steel plates or Dan Flavin with industrial lights.

Consider, though, what Turrell had to do with Minimalism in the first place. I mean aside from his age and his interest in earthworks out west, like Roden Crater in Arizona. He long made the visitor's presence part of the theater, as on sunsets at PS1. One shivers with the winter chill as a rectangle cut in the ceiling becomes a cloud of light. He also calls attention to the spaces of a gallery, from little more than readymade materials. Carl Andre does the same with steel plates or Dan Flavin with industrial lights.

One can see the convergence of household furnishings and Minimalism—what another show has called "Aspects, Forms, and Figures." One can see again, too, the late-modern ideal of painting as physical object. As with the trendy light boxes of Jeff Wall, the work closest to painting sticks out and weighs the most. It also transforms the space of a gallery, and it depends on the viewer. An illusion, after all, exists only in the eye and mind. Yet it may also offer a space for the viewer. Visitors to PS1 in summer may have to settle for a wall of light or mist by Olafur Eliasson, but those who need a light fix in winter can still thank Turrell.

Turrell's illusions may attract the same friends and critics as a dramatist like Bill Viola. Where Irwin's bare scrim at the Whitney from 1977 makes an illusionist seem overwrought and blustery by comparison, new-media illusions in white light from younger artists try even harder to overwhelm the eye. Anthony McCall and Terence Koh both update Flavin's fluorescent tubes updated for Hollywood sets. As it happens, Barry Diller has opened his Chelsea offices, covered with bulging volumes of frosted glass by Frank Gehry. However, Turrell insists on industrial processes rather than studio special effects. Born in 1943, he still asks one to contemplate real space.

Two sides of the picture plane

Turrell's painterly side exploits symmetry, simplicity, and transparency, and he invites comparisons to Mark Rothko. Sunset turns visitors to Long Island City or to Arizona into Moonwatchers out of Caspar David Friedrich and the Romantic sublime. Yet he also insists on the sensation of light as occupying real space, whether with natural or gallery lighting. As with both traditions, he plays with painting and architecture—again envisioned as plane and volume. His work in New York galleries in 2007 made those two sides explicit. They also allowed one to see the elements of his technical wizardry up close.

With "Light Leadings," Turrell went high tech, in order to pull apart the components of vision. The largest of these works manipulate neon and LEDs like pixels, rather than leave changing patterns of light up to the gallery and the sky. These dwell on his Rothko side, and they assert control. Visitors sit in front of them, while pale, swollen rectangles embedded in large monitors slowly shift in placement, intensity, or color. As in the Guggenheim's lobby today, it took time to realize that anything was happening at all. I cannot swear that I have described any of the patterns correctly.

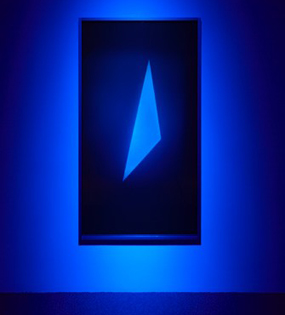

Smaller works from 2007 allow the image to change according to one's movements, while the geometry itself remains fixed. Turrell calls the series "Large Holograms," although they approach the scale of easel painting, and these develop his engagement with space and illusion. At first one may see a diagonal line in electric green against a black field. As one walks past or turns one's head, the line becomes a plane in depth. If one does not recognize these works as artist holograms, one may well imagine that the planes occupy dark, shallow niches cut into the wall. The glass could outline cabinets in a museum of natural history.

I had seen one-color holograms before, although never so dark, crisp, and intense. With a little more effort, I could make the case for these, too, as Minimalism. They represent nothing but themselves, one's own presence sets the colors in motion, and they use a technique as ubiquitous as a credit card. They leave only an industrial sheen up close—except when they dissolve into a rainbow washing over one's head. Mostly, though, they offer a polished work of art and an illusion. Planes slice outward like light sabers, and colored shadows follow one from a distance, like the eyes in an old-fashioned portrait.

A large Chelsea gallery and its winding partitions are by no means incidental. Moreover, the reliance on technology alters Turrell's output from single installations. So many discrete art objects may even invite charges of selling out. The departure from fixed geometry in the LEDs and the diagonals in the holograms also reduce his grounding in formalism. Has he become derivative, only of science more than art? He has long called his works with indefinite and disorienting borders his ganzfields, after a psychologist's term for a state of mental overload. And he did major in psychology at Pomona State, before studying art at UC-Irvine.

Yet Turrell still unites Minimalism with something an Abstract Expressionist would admire. In the museum lobby, one can see more clearly than ever his roots in painting, as both a skill and an analysis of vision. He creates architecture with projected light—and fields of light from museum architecture. Is it still Minimalism or merely a parlor trick? Maybe both, but he continues to show how much Minimalism probed the limits of object, image, and perception all along. Some parlor tricks still take one in after one has explained them away.

James Turrell ran at Pace through April 28, 2007, and through October 17, 2009, and at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through September 25, 2013.