Forever and a Day

John Haberin New York City

Now and Forever: Medieval Time

Terrors, Aliens, and Wonders: Medieval Monsters

"For what is time? Who can easily and briefly explain it? If no one asks of me, I know; if I wish to explain to him who asks, I know not."

Had Saint Augustine lived a few more centuries, he still might not have had an answer, but he could have consulted some remarkable calendars. Unlike our own, they did not change from year to year since, as Augustine pointed out, "for God there is no time." They present only a fixed column of days and annotations. Yet they had to be intricate and exacting enough to allow one to calculate the changing date of Easter—and, with each passing month, the changing hours of prayer.  With their saint's days, signs of the zodiac, and illustrations of seasonal labor, they could embody the paradox that so perplexed him, of eternity and human experience. They also open a show about just that, "The Art of Medieval Time" at the Morgan Library.

With their saint's days, signs of the zodiac, and illustrations of seasonal labor, they could embody the paradox that so perplexed him, of eternity and human experience. They also open a show about just that, "The Art of Medieval Time" at the Morgan Library.

In due course, the Morgan closed its show about medieval time. And then it opened again just weeks later with an invitation to step outside of time and space, into a world of myths and monsters. To be sure, the Middle Ages still had its need to track feast days and harvest days, daily prayers and a changing light. To be sure as well, the Morgan called the earlier show "Now and Forever"—and surely any show asks one to step outside one's limited experience. Yet "Medieval Monsters" evokes lives shaped by unseen terrors, alien threats, and signs taken for wonders. What, it asks, could be more monstrous or more real?

Ritual, toil, and a last judgment

The Morgan embodies the paradox of now and forever in the first show's structure. After the calendars come breviaries and books of hours, to take one from the days of the year to the hours of the day, and then scenes of history. Yet history has to encompass not so much the reign of kings as the reign of heaven. It has to begin with a "time before time," in order to show the creation, and it has to end with a time after time, in order to show the last judgment. In between comes the fall of Troy, perhaps because the Rome claimed an ancestry in Troy's survivors, as in Virgil's Aeneid, and the Roman empire still marked the limits of the known world. The church did, after all, conduct its business in Latin.

The show also marks the Middle Ages as a time between times. It falls between the calendar reforms of Julius Caesar and Pope Gregory, whose Gregorian calendar of 1582 did not quite catch on in parts of Europe until the nineteenth century. Clocks existed as early as 1300, but the Morgan includes just one, in an illustration. Temperance balances it on her head, since she, too, must outlast change. The curator, Roger Wieck, ends with something almost as intricate, the only surviving astrolabe from the era. Its worn wooden disk is difficult to read today, but it had to track multiple scales of time.

While the paradox of time suggests a division between heavenly and earthly realms, their inhabitants would not have seen it that way. Myth and history ran together, just like labor and prayer. Saul appears as a lesson in kingship, for Boccaccio around 1480, much as in J. P. Morgan's Bibles and Morgan's own Crusader Bible—and never mind Saul's madness. Another vivid illustration connects the realms directly. A saint's vision becomes a ray piercing three tiers of heaven, from the saint to her god. (Remember that earlier times thought of ordinary vision as emanating from the observer rather than as light reflected off objects and into the eye.)

Despite its title, the show runs well into the Renaissance. (The San Zeno astrolabe dates to around 1455 in Verona.) It can thus encompass yet another time scale, that of art history. The Berthold Sacramentary, from Germany around 1215, uses gilding to accentuate its thick lines and clashing colors. By the show's end, the glory of Troy has taken on the courtly gestures of the late Middle Ages, much as in a past show of the Morgan's Book of the Hunt. The first calendar insets for labor give way to full scenes of earthly toil and pleasures for the Da Costa Hours by Simon Bening from roughly 1510.

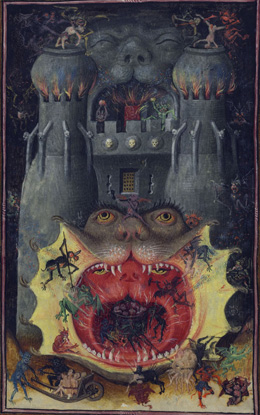

A medieval world of ritual, toil, and a last judgment may sound dismal, but the Medieval masters and illustrators and their readers seem to be having no end of fun. Devils dragging souls to hell in the Hours of Claude Molé, from around 1500, are sure having fun, and the beast and dragon in the Burckhardt-Wildt Apocalypse from the 1290s are no less entertaining. The fires of purgatory rise up from a triumphal arch. Regulars to the Morgan will know the fiery pleasures of the gates of hell in the Hours of Catherine of Cleves from around 1440 as well. Even the hard work of harvest time looks downright relaxing, more than a hundred years before Pieter Bruegel.

Except for the astrolabe, the museum relies almost entirely on its collection. It also supplies detailed explanations for its instruments, so that anyone with enough patience and temperance can play the game. (The apostles turn up in a calendar, because who can resist the coincidence of twelve of them for the twelve months?) Augustine might still be in a state of wonderment, but his best guess sounds refreshingly mundane: "yet I say with confidence that . . . if nothing passed away, there would not be past time; and if nothing were coming, there would not be future time; and if nothing were, there would not be present time." Preserve your memories, pursue your future, and take your time.

Monster hunters

Sure enough, "Medieval Monsters" divides into three sections for terrors, aliens, and wonders. Still, plenty defies categorization—like the three faces of the Trinity under terrors, femininity as alien, and the legend of Saint Christopher under wonders. Mary Magdalene's long hair suffices to mark her as barely transcending the monstrous, and a siren with a sea serpent's tail and claws still gets the wings, musical instruments, and sheer beauty of an angel. Just as telling, the show opens with a genealogy of Jesus and a map of the world, albeit with miniature monsters among its inhabitants. It then displays a family in the wild with an adopted animal and two men in blue furry suits alongside the feats of Alexander the Great. It is not so easy to tell the otherworldly from the everyday.

People, the show suggests, did not even try. They believed in the Bible but also the Holy Grail and the Golden Fleece. They hunted, as noble entertainment and necessity, but they could also see the Annunciation as an allegorical unicorn hunt. They could catalog the imaginary in a study of flora or a bestiary, but as the tools of medicine and a growing mastery of the world. They could depict Jews and Muslims with stereotypical features, but they could also begin to learn from Islamic art—and, although the show does not say so, Islamic mathematics and science. Besides, more fanciful still (and not exactly monstrous), they gave Jesus blond hair and blue eyes to sustain the stereotypes.

They had every reason not to stick to the facts of life. The Middle Ages had its comforts, including a well-defined place in society for each and all, but also the constant terrors of warfare, disease, and deprivation. For the curators, C. M. Lindquist and Asa Simon Mittman with the Morgan's Joshua O'Driscoll, those aspects complement one another: rulers could exploit terror to keep class, gender, and religious hierarchies in place. Aliens were the enemy without, and sins were the enemy within. The mouth of hell was always open.

It makes for a great story. It brings together some of the Morgan's finest holdings with some surprises. Books of Hours are rich in color, like the red field for precious flowers in the Da Costa Hours by Simon Bening. Other familiar manuscript illuminators include Jean Poyer, the Master of Jean Chevrot, and the Master of Catherine of Cleves. Poyer has a female saint taming a monster that has all but swallowed its victim in fine blue stockings. And then he finds a sanctuary for prayer over the slain. Credit Pierre Gringore with the siren's temptations as Les Abus du Monde (or "the sins of the world").

Credit an unknown artist in Bologna or Hungary with the fierce grin of a saint flayed alive. Who needs color, though, when the tale of Jason can approach the shine of stained glass in shades of gray, or grisaille. Who needs to await the outcome of a unicorn hunt when one can fashion a hunting horn from ivory? And while these date from as late as the High Renaissance, a Spanish manuscript from as early as 940 has some of the most striking bands of color and most monumental monsters. The near absence of the Apocalypse seems strange after the devils in Hieronymus Bosch, but its terrors became newly popular after the Reformation—when Martin Luther, John Calvin, and the Church of England chose to see themselves as besieged.

I mention that not because the curators would necessarily agree, but because so much remains unexplained or inexplicable. The capacious definition of a monster suggests an academic's thesis (and the curators are from Western Illinois University and Cal State Chico). The sorting by theme rather than chronology suggests an unchanging world that did not exist. Still, the terrors pay off. Sure, go ahead and include Saint Christopher on the excuse that he was a giant—especially since Bening renders him in miniature. And sure, go ahead and include the wonders of the world, since who can say where the known world ends or begins?

"Now and Forever: The Art of Medieval Time" ran at The Morgan Library through April 29, 2018, "Medieval Monsters" through September 23. The association of the book of Revelations with the Protestant Reformation is a controversial claim by Gary Wills in Making Make-Believe Real, about Shakespeare and the Elizabethan age.