The Big Small Museum

John Haberin New York City

The Scottish National Gallery at the Frick

The Crusader Bible

What is a museum to do? As blockbusters and busy atriums draw the crowds and crowd out collections, what does that leave for first-class museums with no room for either one?

Not coincidentally, those are an art lover's most cherished destinations. They include alternative spaces that take chances on contemporary art. And they offer a respite from the crush of monster museums and the city. Here in New York, one need not identify with the voracious capitalism of Henry Clay Frick or J. P. Morgan to linger gratefully over their private enclaves and collections.  But wait: what if small museums, too, feel the pressure to keep pace with the headlines?

But wait: what if small museums, too, feel the pressure to keep pace with the headlines?

For one thing, they can work together. Ten paintings from the Scottish National Gallery at the Frick Collection offer a modest history of art from the Renaissance through Romanticism. They honor both a museum that one may not see in a lifetime—and one that every New Yorker can call home. They also come as part of an ongoing strategy, of partnerships to bring out the strengths of smaller museums and their permanent collections. Yet they still leave one worrying about the future.

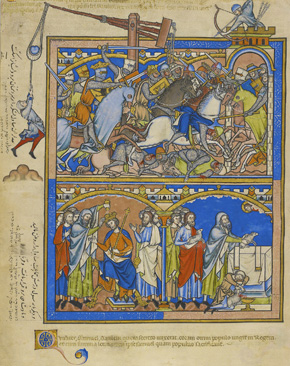

On the subject of small treasures, for a book of heroes The Crusader Bible has few heroics. And it sets them not in the Holy Land, but in France at the time of the Crusades, when Christendom was awfully proud of itself. Based on its costumes, its settings, and its sheer richness, historians assign the volume's patronage to Louis IX, the "crusader king," who would be eight hundred years old this very year. The Morgan Library, which owns most of it, displays roughly half alongside armor and other objects that fairly leap off its pages, including a rough stone meant for a catapult. Believe me, it is heavy. Yet this Old Testament can be a delightfully ragtag affair.

Playing tourist

Even a snob can enjoy playing tourist. I finally visited the Detroit Institute of Arts on the verge of falling prey to bankruptcy. I remember my one visit to Edinburgh the summer before college, although not for the museum. I remember cloudy skies overlooking the central city. I remember being asked the time in a thick accent and not understanding a word. From its ten paintings in New York, though, one can understand the fullness of its art.

Its greatest artists are at their sparest and clearest. Sandro Botticelli around 1485 was just moving from tempera on panel to oil on canvas—and from the grace of his early Venus and Madonnas to the fervor and austerity of his later years. Here the Virgin kneels before the infant Jesus but towers over the viewer, with clasped hands and lowered eyes. Her pink dress matches the flowers fallen to the grassy earth, and the blue of her robe easily outclasses its gold trim, although the green shadows probably have more to do with abrasion. Nature comes with its own sculptural niche in the rocky precipice behind her. Roses stand for suffering, and the sleeping child prefigures his death, but you do not need to know that to share her rapture.

El Greco, too, manages both inwardness and theater. He is everywhere this year, four hundred years after his death—including a room at the Frick for its own holdings and one at the Met for both its collection and the Hispanic Society's. Then again, El Greco is always popular in New York, where two versions of this painting already appeared in a retrospective. A boy blows on an ember, bringing him closer to the man and woman he illuminates. Is the older man's toothy grin the mark of an ape or a fool? Perhaps, but one is happy to join this intimate circle.

Some twenty years later, Diego Velázquez captures the immediacy of the new century. This is 1618, before his more elaborate court portraits, with a thrilling simplicity. A servant boy and an old woman preparing are pressed up against the picture plain. A paint drip across the gleam of ceramics displays a painter's virtuosity, but also his honesty. So does the tension in the shared gaze across the span of a human life. Scenes like these, called bodegones, anticipate Dutch genre painting, but without the moralism.

Obviously drama is the order of the day. Scotland itself gets to show off. A Scottish artist, Henry Raeburn, allows a friend to dress up in tartans—and Raeburn to present himself to the Royal Academy in 1812. The wife of a Scottish lord slouches to one side of an armchair for John Singer Sargent in 1892, without sacrificing her high style and piercing eyes. Another Scottish artist around 1759, Allan Ramsay, even takes showing off as his subject. A woman arranging flowers, backed by picture frames, insists on the seriousness of artifice and art.

John Constable, too, is at his showiest, around 1827. Regulars at the Frick will know the revolutionary precision of his cloud studies. Here he is past fifty and going to town, in a dark landscape nearly five feet tall. Stacked clouds must compete with an even wilder tree exceeding the height of the canvas—and a distant cathedral with foreground plants. Whites fleck the impasto surface. If Scotland secedes from England, it will be taking a panorama of England with it.

Collections matter

If some things get superficial, that comes with playing tourist. To the extent that the selections have a high purpose, part of it is geography. The show duly includes such British artists as Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough. If Constable is at his most Romantic, so is Gainsborough—moving toward what a recent show called "The Untamed Landscape." Around 1750 he starts with the logic of the Enlightenment, every passage into depth given a path. Yet he also introduces natural life, crumbling river banks, competing curves, and improbable leaps of scale.

The selections also complement the Frick. El Greco, Velázquez, and Constable are all at home here. So are men and women at leisure in a park, by Jean Antoine Watteau. Gainsborough builds on Dutch landscape, like those of Hercules Segers or one from Jacob van Ruisdael also in the museum. As for Sargent, Frick himself turned down this very portrait. It goes well with standing portraits by James McNeill Whistler, who favored the same loose brushwork and fashion sense.

Can a small museum, then, retain its purpose? By joining with others, it seeks wider attention while focusing on the core of each in their permanent collections. The Frick has shown work from the Norton Simon in Pasadena. It has given Dutch painting from the Mauritshuis a temporary home during remodeling. It has also worked before with Scotland, for a display of drawings in 2000. It is partnering as well with the de Young in San Francisco and the Kimball in Fort Worth, the present show's last two stops.

Can a small museum, then, retain its purpose? By joining with others, it seeks wider attention while focusing on the core of each in their permanent collections. The Frick has shown work from the Norton Simon in Pasadena. It has given Dutch painting from the Mauritshuis a temporary home during remodeling. It has also worked before with Scotland, for a display of drawings in 2000. It is partnering as well with the de Young in San Francisco and the Kimball in Fort Worth, the present show's last two stops.

If one revels in smallness as a mark of integrity, the New York stop is the smallest of the small. After that, the show will grow to fifty-five works, and I wish I could see them. The museum directors themselves make the selections. Still, one cannot make the pressures on museums go away. People did line up this for Jan Vermeer and Girl with a Pearl Earring on loan from the Mauritshuis. It was a blockbuster in miniature.

Tired of museum atriums? The Morgan Library added one in 2006 designed by Renzo Piano, the architect of the Whitney's move to the Meatpacking District. Value alternative spaces like SculptureCenter and P.S.1? The first has just expanded, and the last is now MoMA PS1. The Frick itself has proposed expanding into its gardens, after a brief stay offsite as the Frick Madison, promising public access to the mansion's second floor and (ouch) a bigger reception area. If it once swore that things would remain as they are permanently, its director told The New York Times, "Permanent meant a garden that would last for at least a few years."

What is a museum to do? Doublespeak aside, I am with the Frick, so long as it remembers that collections matter. Gaining attention is part of remaining relevant, but so is the heart and soul of a museum. Perhaps Watteau provides an allegory with his Fêtes Vénitiennes from around 1719. Seventeen courtly men and woman angle for a place in their garden, along with a statue and an urn, and the artist puts his face on a musician, but not everyone can be a winner. One can show off to one's delight, but those delights may soon be gone.

The last crusade

The forty-eight sheets of The Crusader Bible stick to Biblical narratives, from the Creation to King David, whose life takes up nearly half. Two horses meet head to head as in a friendly joust, far from the tragedy of the actual Crusades for Wael Shawky, and other horses in tight formation might be smiling, but major battles descend into chaos, their warriors thrown all but indistinguishably together. Saul at the head of his armies draws back in fear, Samuel can barely raise himself from bed at the call from heaven, and others from Adam to Boaz are at their best asleep. Saul bringing peace might be showing off his pet hamster, while a boy beside the altar slits the neck of a sacrificial lamb like something he does in his sleep. David outsmarts Goliath, but then he looks like a wise-guy taking it out on the less than cool kid, and he spends the rest of his scenes bent on murder, adultery, and betrayal. As for that stone, the soldier launching it dangles helplessly to serve as a counterweight.

Such is the creativity and charm of a Gothic masterpiece, as vivid as when an artist like Barbara Wolff opens the Hebrew Bible or the Book of Ruth today. The scenes have few outright villains. The pages from Joshua downplay divinely ordained mass slaughter, and even sin, death, and dismemberment take on the trappings of a gentler comedy. Adam and Eve follow their maker like teens in need of a mentor, and Noah does not have to deal with the dying or his own drunkenness. A woman swoons in the supporting arms of what one knows are her rapists. One could be reading not an illuminated manuscript from around 1250, but a graphic novel.

In a way, one is—and not just because the missing sheets are posted online, curated by William Voelkle. Also known as the Morgan Picture Bible, it earned its name by telling stories with images alone, unlike so many of J. P. Morgan's Bibles. Its Latin captions date from decades later and Persian inscriptions from a later stop on its long and winding road to New York. Historians, who can detect the hands of at least half a dozen artists, are still piecing out its making. While the show runs roughly in the order of the Bible, sheets necessarily pair early and late scenes, much like the front and back pages of a newspaper lying "across the fold." Samuel's mission from heaven follows a patriarch's deathbed blessing, and both bear an expression that would go quite well with the word oy.

If that makes it harder to sort out the battles, the births, and the beds, much less the masters of the medieval world, think of it as a challenge. Go ahead: is that Jesus dragging his cross? Nope, it is a young Moses bringing fertility to the ground. Common motifs, or "type scenes," help unite the many artists, like a king holding out his arms as a gesture of generosity or grandeur. They also allow meaning to arise from variation, as when a betrayed wife interrupts that very gesture to stick out her tongue.

Unity also enters in a shared style—less delicate and intricate than the later International Style, but also further from The Medieval Hunt, medieval time, and everyday life in the medieval world. This Bible has a broad humor and a humble charm. It offers nothing as private as a queen's Book of Hours at the Morgan just weeks before. Pages have from two to four scenes, framed by city walls and towers. As the Bible unfolds, characters tumble beyond the borders.

Is that a sign of artistic evolution or the needs of the story? Probably just different artists, but do not be too sure. After Genesis, gold gives way to blue skies and plain interiors, except for pagan idols destined for destruction. A touch screen at the Morgan invites thoughts of progress, too, inviting one to zoom in on an anxious smile—and to guess what one will see after zooming out. Art is on the verge of the greater weight and insight of Cimabue, Giotto, and the next century. First, though, Europe had to set aside its crusades and its heroes.

Paintings from the Scottish National Gallery ran at The Frick Collection through February 1, 2015, "The Crusader Bible" at The Morgan Library through January 4. The press quoted the Frick's director on November 10, 2014.