Bible Stories

John Haberin New York City

J. P. Morgan's Bibles and Medieval Money

Belle da Costa Green: A Librarian's Legacy

Why did J. P. Morgan assemble the Morgan Library? It was not just because he liked to read—although the three-tiered shelves and walkways of his private library, still a highlight of the larger public institution today, could make anyone a reader without so much as opening a book.

He collected to show his humble deference to scholarship and art. He could show his piety as well in what he collects. At the same time, he was boasting of his wealth—a wealth of knowledge, power, and cash. How appropriate that two shows now focus on Morgan's Bibles and medieval money. They and a smaller show of "Early Modern Herbals," or age-old guides to the healing properties of plants,  also single out a century or two when all these things came to be. "Morgan's Bibles" takes special pride in them all, with an emphasis on Morgan himself.

also single out a century or two when all these things came to be. "Morgan's Bibles" takes special pride in them all, with an emphasis on Morgan himself.

Before there was capitalism, there was money. Think of Judas and his thirty pieces of silver. Matthew, before becoming an apostle, might have collected taxes on it. It may have been a flimsy thing or awkwardly bulky and heavy, but a lot turned on it. Now the Morgan makes the case for just how much, in "Medieval Money, Merchants, and Morality." If it has a discomforting moral for an institution founded by a man of means to display priceless possessions, it may say more than the museum ever knew.

In 1924, eleven years after J. P. Morgan's death, the Morgan Library opened to the public. His son relied on it too little to keep it to himself and respected it far too much. Its outreach has grown ever since, from galleries where Morgan once had his home to the garden where visitors can imagine walking beside him. It still has the feel of a private treasure that they, too, can call their own. A nook out by cafeteria has children's books for those too young and too in love with words to prefer high tea. It may have lost its serenity and dedication since Renzo Piano added an atrium, but now another presence walks alongside you as well, Belle da Costa Green.

What Morgan collected

Of course, the same questions arise with collectors today as with Morgan—all the more so when museums (yet again) exhibit a private collection. (Yes, that means a gift coming up, one just for the medieval world.) How are collectors, even one as savvy and sensitive as Spike Lee, distorting the role of museums and the art scene? That includes the Morgan's own turn to recent art. How refreshing, then, to return to a time when J. Morgan was just getting started and could not stop. "Morgan's Bibles" sticks largely to what he himself collected and its role in the collection to this day.

Not exclusively, mind you, and the Morgan does not make it obvious when his choices end and others begin, but close enough. It also has an expansive view of the Bible. It includes psalters, of course—not just the Psalms and prayers taken from the Bible, but also a setting to music on behalf of John Calvin. Who knew that the stern Protestant preaching original sin wanted you to sing? It has drawings and prints merely because their scenes draw on the Bible, but then how much older art does not? A porcelain of the Holy Family comes close to the viewer in proximity and scale—enough to put anyone in the place of the shepherds or the wise men.

Artists as different as William Blake and Filippino Lippi depict Job close to despair. His "comforters" gesticulate cruelly for Blake, dutifully for Lippi. A drawing by Anthony van Dyck displays his command of anatomy and vitality, even as Jesus is as grisly as death. The show has among the largest of Rembrandt prints. He bathes the crucifixion in a shower of light, even as the thieves on the cross and the mob on the ground sink in darkness. He shows the mocking of Jesus as a multi-tiered display of statues, spectators, heroism, and abasement. Rembrandt's scratchy, compulsive line has never been more evident.

Still, an expansive show makes sense given the roles of the Bible in real life. Morgan had more than one role as well. Even while he nurtured his library, he served as president of the Metropolitan Museum, doing far more for its growth than many a curator today, much less presidents overburdened with fund-raising. He also considered himself a devout Episcopalian, which did not in the least stand in the way of showing off his love of wealth. Some books are leather, enhanced with clasps, crystals, and other finery, some embroidered. Here you can tell a book by its cover.

His scholarship appears from the start, with a Bible that divides its pages into blocks for Hebrew and other languages. Scholarship appears, too, in German and English editions. The Morgan has famous translations by William Tyndale and Myles Coverdale in the 1500s, the Great Bible commissioned by Thomas Cromwell for Henry VIII, and a King James Bible first edition. They testify to two more roles for the Bible as well, reaching our and reaching kings. Embroidery was largely limited to a guild with privileged status, but not entirely. Anyone with a needle and thread could, at least in principle, give it a go.

Like other illuminated manuscripts, these also testify to a role in art history. The delicate realism of a Bible from Tuscany dates to the 1490s, before a Renaissance in sculpture and painting. As late as Peter Paul Rubens, artists were still copying miniatures as well. Always, though, Morgan was out there collecting. Photo shows him with Egyptian art in desert sands and taking lunch in a Persian temple. Whether the message of the Bible reached him I leave to you.

Your money or your life

"Medieval Money, Merchants, and Morality" gives new meaning to "your money or your life," the afterlife. When Hieronymus Bosch painted Death and the Miser, with sacks of money tempting a man on his deathbed, he was taking up a subject familiar from illuminated manuscripts and Sunday sermons. If a deathbed seems an unlikely place to accumulate wealth, it is only, after all, a parable. The show includes Petrarch and Geoffrey Chaucer, who wove the message into their poetry (although Chaucer also makes the case for merchant cunning). Bosch himself had an unmatched talent for bringing an older world view to the very height of the Renaissance. As his interior passes into depth, in proper perspective, it presents one temptation after another in cabinets, shelves, and doors.

More than half the show elaborates on that message. A still more lavish deathbed scene appears in The Hours of Catherine of Cleves from around 1440, across from the fire of Purgatory. Boys in another book of hours scramble for a shower of coins, ignoring the Visitation of Mary and her mother on the facing page. A saint flees an entire golden mountain, by Fra Angelico, while gesturing toward an actual city on a hill. With Albrecht Dürer, the prodigal son at last comes home. If accumulating wealth is bad, spending is worse.

It was not too late for the prodigal son, and it is not too late for you. So at any rate goes the story, but has its moment already passed? Bosch's painting teems with devils,  and devils always put on the best show. Those boys scrambling for money could be your neighbors at play. One work on display is more lavish than the next, from the gold leaf of medieval painting to the subtler richness of the Renaissance. Saint Francis may have renounced worldly goods, but a Renaissance collector possessed Giovanni Bellini's Saint Francis in the Desert.

and devils always put on the best show. Those boys scrambling for money could be your neighbors at play. One work on display is more lavish than the next, from the gold leaf of medieval painting to the subtler richness of the Renaissance. Saint Francis may have renounced worldly goods, but a Renaissance collector possessed Giovanni Bellini's Saint Francis in the Desert.

Those contradictions run happily through the show, right down to its title. Is this medieval money, merchants, and morality? Not just morals are changing. A show that opens with Bosch cannot be all that medieval, and sacks of gold are not yet money. (Wikipedia assigns a present-day equivalent for thirty pieces of silver, but I am not so certain.) Bosch hangs next to an imposing strongbox and actual coins from the late 1300s, so flimsy that one might mistake them for paper tokens in a child's game.

The exhibition tells a different story as well. It is about the emergence of a new merchant class and the spirit of capitalism—for whom wealth was a mark of divine favor and charity is owed to only the "deserving" poor. By its end, money becomes more intricate and weightier. It had to do so, because coins at first established their value by their weight. And then mere paper takes on arbitrary value as well. If a medieval manuscript has its unmatched glories, a merchant's register or a text on money management is a book, too.

The curators, Diane Wolfthal and Deirdre Jackson, add two paintings, for additional stages in a Renaissance economy. They are not just displays of wealth, like so much art in Tudor England, but portraits of getters and spenders. The first, by Hans Memling, a man in black holding a pink carnation, hesitates to speak of just what he does for a living—but the second, by Jan Gossart in 1530, glories in it. The tools of this man's trade have the magic of still life, and his records hang like wallpaper. They foretell a time when wealth can go not to charity or the church, but to a library like Morgan's, and the party of religious zealots can favor tax cuts to the wealthy. Fitting or chilling, a camel need no longer go through the eye of a needle for a rich person to enter the kingdom of God.

Passing or to come

Jack Morgan rehired his father's personal librarian and appointed the Morgan's first African American director. Did you know that they were one and the same? If not, you are hardly alone. In her own time, Belle da Costa Green passed for white. An exhibition calls her "uncompromising," but was it a compromise or an act of defiance? For its centennial, the Morgan seeks "A Librarian's Legacy."

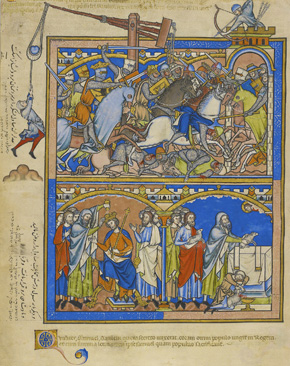

The Morgan's anniversary celebration began with that display of Bibles and, in delicious counterpoint, Medieval money. And surely anyone who worked so closely with a wealthy man who fashioned himself a scholar had to respect his tastes. And, sure enough, "A Librarian's Legacy" gives due space to illuminated manuscripts like The Crusader Bible. It shows off not one but two Rembrandt prints, including one long known as The Hundred Guilder Print for its public presence and its cost. Still, she plainly exceeded Morgan's scholarship and shared his tastes. This was not a compromise but a true collaboration, where the family of Henry Clay Frick went it alone.

How, though, did Belle Marion Greener, a black kid from Washington, D.C., become Belle da Costa Green? And how did she become the librarian of an outstanding collection while still in her twenties? The curators, Philip Palmer and Erica Ciallela, give her both the museum's most prominent galleries—the first for her story and the second for her work. Born in 1879, she grew up in the north of the city, closer to Howard University, the historically black college, than to the Capitol. Still, her father, headmaster of a segregated school, was the first black graduate of Harvard, and her mother's family valued class and education as well. They had a society wedding.

On their separation, her mother took her to New York and changed their name. It was a new life, with bustling streets and a picnic up the Hudson. She served as librarian at Princeton before leaving for Morgan in 1905, while its Charles F. McKim building was still underway. Still, it was the age of Jim Crow, public lynchings, and racism that embraced its name. A photo by Alfred Stieglitz shows Jean Toomer, a leader in the Harlem Renaissance who became a Quaker and left for rural Pennsylvania. Passing, it seems, is what you make of it.

Greene made the most of it, and the press found her irresistible for her achievement, good looks, and fashionable comportment. So did such photographers as Charles White, who shows her profile, her head duly raised. When she lets her guard down for a smoke, that was a pose, too. The show's second half centers on her imposing desk, but she did not sit still. She took her expertise and selections from the Morgan to New York's Public Library and the 1939 World's Fair. She oversaw conservation of a work after Botticelli that hung and still hangs among lesser Renaissance paintings in Morgan's study.

Just what, though, did she contribute? The show has plenty of evidence, including ledgers and a library card, but few answers. Past shows have slighted her in favor of Morgan and present-day curators, but still she has her range, from the Middle Ages to twentieth-century work that her patron might never have swallowed. She thanked Abraham Walkowitz personally for his 1913 Human Abstract. And, in her own less than obvious way, she had her race. Years before, her father had appeared with Frederick Douglass in a print of leading black Americans, and one of her last acquisitions was a letter from Douglass, before her death in 1950.

"Morgan's Bibles" ran at The Morgan Library through January 21, 2024, "Medieval Money, Merchants, and Morality" through March 10. Belle da Costa Green ran through May 4, 2025.