After the Carnival

John Haberin New York City

Curtis Talwst Santiago and Ebecho Muslimova

Gabrielle l'Hirondelle Hill

This may be the saddest carnival that I have ever seen. Curtis Talwst Santiago sure promises a celebration when he takes as his alter ego the J'ouvert knight, from a Caribbean carnival, but he is putting himself on the line, too. But then ouvert in French can mean open in the sense of frank as well.

A year later at the Drawing Center, Ebecho Muslimova merely hangs out in the basement, with her studio and her butt. Both see the international art scene as itself a carnival, with themselves as its main attraction. Further uptown, at the Museum of Modern Art, Gabrielle l'Hirondelle Hill mixes a sense of history with addictive pleasures, too.  She takes tobacco as materials and as property of North America's indigenous peoples. She can make art as dark as tobacco-stained rags or as cute as a stuffed toy. Are all three recovering their heritage or just carrying on?

She takes tobacco as materials and as property of North America's indigenous peoples. She can make art as dark as tobacco-stained rags or as cute as a stuffed toy. Are all three recovering their heritage or just carrying on?

Lost in translation

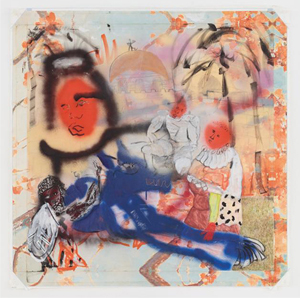

Curtis Talwst Santiago knows the power of translation. J'ouvert translates literally as I open, but it serves in common usage to denote a new dawn and a new day. It also serves in a Caribbean carnival as a vital connection to the past. Of Trinidad descent like Chris Ofili, Santiago seeks a personal connection as well. He embraces the role on video, as a dancer and recording artist. His texts and images run from Europe to the New World, with some strange stops along the way.

One reaches him only through what could be a construction site or a disaster area, with his striped costume abandoned on the floor. Whatever is it, chain armor from the Hudson Bay catalog? A figure in a painting lies slumped as well, with a helpless or sheepish smile. Come to think of it, Santiago's jumping and weaving can look a little pathetic, too. There is joy here all the same. The installation under construction is common enough these days, but it is still reliably funky and fun.

He throws in a second helping a few feet away and in a Lower East Side gallery. Spray paint and charcoal impart a healthy cheer and a closeness to street art. They also place the storied knight in the company of a saint and a blue devil, a trickster worth heeding, too. The spray also includes white, so that everyone emerges in a glow. The carnival may have departed, not its energy. It also leaves behind a complicated history.

The show's title, "Can't I Alter," could come as a demand, but it leaves open just what Santiago wishes to alter. The center devotes its back "drawing room" and downstairs "lab" to an older Chinese artist for whom nothing seems to change. Born in 1942, Guo Fengyi had to retire early from work in a factory because of arthritis, but it did not keep her from the detailed weave of colored ink from around 1990. The factory may have produced modern chemical fertilizer, but she bases her drawings from around 1990 on traditional Chinese medicine, wellness, and healing, as well as cosmology and myth. They serve her as private symbol systems, like those of Hilma af Klint in the early twentieth century, although on found newsprint. They sustained her even after her hands had failed her, until her death in 2010.

Santiago has to explain himself, too, and the tale is a total mess, like his spray paint. But then, he implies, so is his background, starting with his birth in Canada, and he is all the happier for that. The knight took its present form in a seventeenth-century novel, but he also leans on a mural from thirteenth-century Lisbon and a figure in a public square in an early Italian Renaissance painting. Large hangings look like traditional quilting, but they derive from polychrome copper in a tomb in Ethiopia. Other pretend artifacts include silver jewel cases, modeled after saintly reliquaries from the Middle Ages. A craggy rock riffs on mesolithic ruins, but a more polished glass sculpture looks just as fragmentary and as ancient.

It also looks like an enormous nose, and Santiago is thumbing his nose at history, at himself, and maybe at you. (Tomb robbers, he explains, used to steal noses from Egyptian statuary.) The show may not add up, not when it comes with such lengthy explanations. Still, it speaks to the vitality of old stories and the need to question history. It places him firmly within the Afro-Caribbean diaspora as well. Like Renée Stout, he is still discovering his ancestries and himself.

What a dump

Ebecho Muslimova has a studio to die for, with track lighting and no end of space. So why is she sitting in a trash can? And why is she taking her time for anything but making art? Or is it only her alter ego, Fatebe? Surely Muslimova knows better, right? I would not be too sure, in "Scenes in the Sublevel" at the Drawing Center.

It is her Phantom Cage and the show's largest work, and nothing seems to scare her—not confinement and not her ghosts. She welcomes as many as will fit, and that is saying a lot. The studio's high ceiling has room for butterflies and balloons galore. A second Fatebe, chin on her arm, is bemused, while Fatebe in the foreground is downright ecstatic. So she is throughout, whether resting on a sofa or, in another painting, swallowing the sofa whole, along with its old-world charm. The bumps of its red upholstery could be her candy.

It is her Phantom Cage and the show's largest work, and nothing seems to scare her—not confinement and not her ghosts. She welcomes as many as will fit, and that is saying a lot. The studio's high ceiling has room for butterflies and balloons galore. A second Fatebe, chin on her arm, is bemused, while Fatebe in the foreground is downright ecstatic. So she is throughout, whether resting on a sofa or, in another painting, swallowing the sofa whole, along with its old-world charm. The bumps of its red upholstery could be her candy.

Still, "what a dump." I quote Martha in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, the play by Edward Albee, doing her best Bette Davis imitation—and Albee might have appreciated show's mix of high art and pop culture. But this really is a dump. The show could be the dark undercurrents of Muslimova's imagination. It unfolds in the Drawing Center's dark underbelly, too. It occupies the basement "lab" (with David Hammons leaving his mark upstairs) and the bemused version of her rests on stairs very much like the ones leading down.

Conditions could only be worse in her native Russia, which she left as a child. Still, is Muslimova really off the hook? Fatebe aside, I have little patience for a cartoon style in painting, in Cao Fei or in "Dreamlands." And her black outlines owe plenty to cartoons. She can try my patience, too, with what a group show called "Idols of Perversity." Still, she is aware of her limits, and that ambivalence sets her apart.

So do the transformations. Fatebe might have her butt in the trash. She might instead, though, have become the trash can, the industrial sort with a ribbed metal surface. Her breasts drape over it and her thighs (the fat in Fatebe) stick out from below. Elsewhere she becomes a giant heirloom tomato with its roots beneath the floor. Dabs of paint morph into those balloons.

Muslimova gets their colors from enamel and oil on aluminum, in panels eight feet tall (although in a center devoted to drawing). When Fatebe hangs upside-down from a beaded curtain, I still cannot say whether the red beads are real. Is she just enjoying herself, and is she reaching from the trash for a glass of wine? She is shameless enough, for sure. When she takes in her reflection in a pool of liquid, there is no crying over spilled milk. As for Muslimova, she must be enjoying herself, too.

Small tobacco

Gabrielle l'Hirondelle Hill is not apologizing for big tobacco. Just for starters, she is not one to apologize. Titles speak of Desperate Living and Vomiting Anger. Her largest sculpture, a nearly life-sized nude, lies seemingly etherized on a table—but with eight breasts, flaming red lips, and wildflowers for eyes. She has the west wing of MoMA's 2019 expansion, but she looks the other way from unchecked corporate or museum growth. Tobacco for her is material for art and the handmade.

Then, too, this is small tobacco indeed, and it recalls when Native Americans did the farming. Hill, who identifies as Métis (or half indigenous and half French Canadian), works in British Columbia, in unceded tribal land, but she claims a heritage, too, in Manhattan. Long before MoMA came to midtown, she explains, a tobacco plot stood in today's Greenwich Village, in care of the Lenape people. In the closest she gets to an installation, two flags hang high, but reduced to stained and weathered rags. Dark as flags for David Hammons but without the colors of the African National Coalition, they could serve as a memorial to what can never return. Behind them, black spatters a long white wall.

When it comes to tobacco, she cannot get enough of it, and it does not depress her in the least. It serves as stuffing for her sculpture and darkening for the flags. Infused in Crisco oil, it becomes a medium for collage and painting. It also serves for stories, and Hill has more than one to tell, counting wall text. They just happen to be more interesting than the art and no more connected. For all the anger, they are also mostly upbeat, and so is the work.

One set of stories picks up the history of tobacco, even as native peoples lose control of its destiny and theirs. Read on, and it served as the colony's first currency and, adapted by the British, as backing for moneys in payment toward wages, taxes, and fines. It was in effect the gold standard. A second set enters the works on paper, her "Spells," with hints of still life, nature, and abstraction. They are low key, bright, and welcoming—even if, as a title has it, Those Streets Are Gone. They contain all sorts of things, and Crisco is the closest they get to good old painting in oil.

A third set of stories circles back to a woman's life, again without apologies—apart, perhaps, from dependence on tobacco. Hill stuffs pantyhose for her nude Counterblaste, before adding the breasts, oversized lips, and beer can pop-tops. She abstracts another to a butt and legs, in the manner of early modern sculpture. Other stuffed pantyhose is still more cuddly and far more innocent, as bunny rabbits, although not as cheerful as Native American art for Jimmie Durham, Jeffrey Gibson, Carolina Caycedo and David de Rozas, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, and the Brooklyn Museum with its Brooklyn Artists Show. But then the nudes amount to sock puppets. Mixed messages anyone?

If so, for all its costs, that ambivalence may rescue the art from itself. Hill speaks of "the indigenous economic life of tobacco," which sounds suitably high-brow, but then there are the butts and the bunnies. She also shares MoMA's projects gallery with a show of "Broken Nature," which seems itself unable to decide whether its teams of artists and scientists are rescuing nature from humanity or from itself. To confuse you further, the curator, Lucy Gallun, is from the museum's photography department. Still, Hill is open to thoughts of "reciprocity" and "interdependence," with the spatters as Dispersal and Disintegration. Big tobacco deserves the kick in the butt.

Curtis Talwst Santiago ran at the Drawing Center with Guo Fengy through May 10, 2020, and at Rachel Uffner through April 26. Ebecho Muslimova ran at the Drawing Center through May 23, 2021, Gabrielle l'Hirondelle Hill at The Museum of Modern Art through August 15.