Holy You Know What

John Haberin New York City

Chris Ofili

After all these years, Chris Ofili has still not put the scandal of his arrival in New York behind him. He just discreetly leaves it in the stairwell.

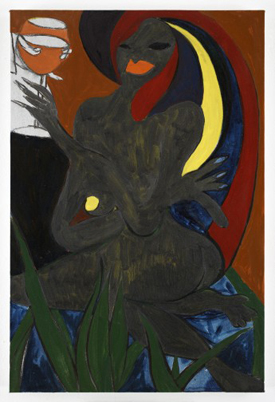

He also leaves the roots of an artist steeped in piety and good intentions. "Night and Day," a retrospective at the New Museum, shows his search for "Afromuses" and black identity. It shows him staking out African and Western culture, from Titian to Modernism and from Zimbabwe to Trinidad. It shows him gaining as a colorist and installation artist, with two floors of twilit "architectural environments"—the dark night to his early day. It also shows his delight in the offensive material that once scandalized New York, as displayed in that stairwell alcove. It may not silence cultural conservatives, but it does all it can to meet them on their own terms, sanctity and all.

Making a sensation

Of course, it was quite a scandal, and the New Museum has quite a stairwell. Ofili depicted The Holy Virgin Mary in 1996 with map pins, glitter, and ample black flesh barely concealed by a loose green robe. That flesh also sported an exposed breast fashioned from elephant poop. Speaking of map pins, Mary put him on the map. When she came to the Brooklyn Museum in 2000, in "Sensation," Mayor Giuliani denounced the painting as a sacrilege. The museum was looking for a sensation, and it got what it wanted.

Born in 1968, Ofili encountered elephant dung in 1992 on an art study trip to Zimbabwe, and he went bat shit. He had found something at once native to the continent, pitch black, and redolent of life. He carried as much as he could back to London and set right to work. Shithead from that year consists of turds, human hair, and human teeth. Its devilish grin in black and white still draws a smile, along with lasting unease. Only the smell has faded.

That stairwell has its limits, though, and so does the sculpture. The stairs run all of one floor, before obliging a return to enclosed fire stairs and oversized white cubes, and the work flaunts its cartoon primitivism. This is African art in black face, so as to claim the authority of both deep history and the street. It uses hair as hair and teeth as teeth, because art is just too important to traffic in illusion. And it smiles because human impulses, whether for good or for evil, are just too plain to traffic in menace. Ofili will take nearly twenty years to see past blackness to darkness.

Soon enough he was incorporating more poop in large paintings, along with the pushpins and the glitter. The show's first room has a dozen of them. One can only wonder what customs and health inspectors thought at London airport, but no one can doubt what the art scene thought. Mary entered the Saatchi collection, the source of "Sensation," and the headlines. The paintings already show a gift for installation, each leaning against the wall while resting on two more turds. They also show an unfortunate gift for the obvious.

Not all their subjects are heroes, but all of them boast of black identity. Even in Pimpin' Ain't Easy, Ofili is taking it easy and having fun. Its androgynous figure pleads for sympathy, from its bright background to its broad smile, with a visual pun on breasts and balls. Other characters appropriate African "monkey magic," reggae, and Auguste Rodin, for a decidedly extroverted Thinker. Increasingly they create their own legend, about a certain Captain Shit. Their style falls between Jean-Michel Basquiat and a graphic novel.

A black artist had dominated press coverage in Brooklyn—and an artist about as far from histories of race in America as one can get. That says more about divisions of race and class as his art ever could. It also shows a talent for controversy, without the need to represent anything controversial. Ofili portrays the Virgin as something between an earth mother and Aunt Jemima. Even the medium seems at war with itself. The dots of elephant dung nestle amid paint and pins, more suggestive of pattern and decoration than of sewage and raw earth.

Art deco rebellion

Ofili may have trivialized his theme and his roots, but one has to accept his profession of faith, even if Giuliani did not. By the end of the 1990s, he is pushing his religiosity closer to Africa, with a series of Afro Green, Afro Jezebel, Afro Love and Envy, and Afronirvana. He is also becoming more of a colorist, while drawing his colors from the African National Congress flag. Yet he is not abandoning Christianity—or black flesh. Saint Sebastian from 2007 replaces the arrows of martyrdom with iron nails, much like the nails in Gunther Uecker back in the 1960s or planes for Michael Richards. From a distance, it could be a bird in flight.

Ofili's sculpture also offers the first hint of a dark side. A skeletal crucifixion missing its cross becomes The Almighty Shadow. A bearded angel of the Annunciation humps Mary's polished bronze from the rear. First, however, the artist finishes his run of New York City with more comforting role models. His watercolor Afromuses, based on street life, hang solely and in pairs. Most face forward or in profile, for added dignity.

They took Ofili until 2005, when nearly two hundred went on display at the Studio Museum in Harlem. The retrospective recreates just one wall. Again one can see a growing interest in installation. The pairings lead to a broken grid with gaps for the eye to fill. Working in series also means working fast, and the retrospective concludes with two more series of paintings, one to a floor. They come as close as any artist could to taming the museum.

Each has a richer environment than anything he had displayed before. A handful of works in pencil from around 2005 approach abstraction, with the curls of African hair as vertical zips out of Barnett Newman. And one series fills an octagonal room like another landmark of Modernism in America, the Rothko Chapel. These paintings encourage contemplation by their deep blue, an allusion to the Blue Rider movement, Wassily Kandinsky, and the origins of abstraction. The final floor includes flat fields of color, with echoes of Paul Gauguin and Henri Matisse. They hang on walls patterned with foliage in seductive violet. As one passes from one floor and one late series to the next via teeth and elephant turds, one can appreciate what he has left behind.

As curators, Massimiliano Gioni, Gary Carrion-Murayari, and Margot Norton skip past one more series, from 2006, the year after a move from London to Trinidad. Ofili found Gauguin's Tahiti and Matisse's Oceania in the Caribbean, but hardly all at once. That series reverts to opposing pieties: while the mayor who once denounced Ofili's Virgin Mary ran for president, the artist was once again finding religion. In "Devil's Pie," he portrays the seductions of modern life as embodiments of the seven deadly sins. They have fatal human flaws, but not yet the alluring darkness.

As curators, Massimiliano Gioni, Gary Carrion-Murayari, and Margot Norton skip past one more series, from 2006, the year after a move from London to Trinidad. Ofili found Gauguin's Tahiti and Matisse's Oceania in the Caribbean, but hardly all at once. That series reverts to opposing pieties: while the mayor who once denounced Ofili's Virgin Mary ran for president, the artist was once again finding religion. In "Devil's Pie," he portrays the seductions of modern life as embodiments of the seven deadly sins. They have fatal human flaws, but not yet the alluring darkness.

The suavely decadent men and women recall the fear and loathing of German Expressionism and "degenerate art." Even in Biblical scenes, they may prefer black tie and tails to bling or stiletto heels, a slow dance to a blow-out. They also rely on curved fields of black and decorative color, like poster reproductions of Romare Bearden or art deco. They stand at a remove from real overindulgence in contemporary society, whether in the ghetto or in a condo. Like Marilyn Minter or Aneta Grzeszykowska with their feminist porn, Ofili cannot resist temptation, even as he disdains it. He is having his art deco rebellion.

Beyond good and evil

The retrospective's top floor has some of the same stories and colors. Ofili is replaying art history as morality tale. One can see growth all the same. Maybe it is the installation, or maybe it is a growing empathy. Maybe it is the growing command of styles past and present. Either way, the stories are becoming his.

The martini drinkers come with less finger pointing. One even sports a yellow halo to go with her orange nails. Next to it, a nearly abstract Lazarus rises from the dead. Look again, too, and suffering penetrates the darkness. Ofili tackles the suicide of Judas, in deep blues that make one struggle to find an ending. The title alone, Iscariot Blues, allows agony to emerge from creativity.

Ofili's subject matter keeps broadening, along with his interest in design. He collaborated on a ballet about Diana and Acteon, based on a tale from Ovid and a painting by Titian in London's National Gallery. After Acteon saw the goddess bathing, she turned him into a stag to be torn apart by his own hunting dogs. Maybe humans are no worse than the divine after all, and maybe neither Christianity nor Africa has a monopoly on divinity. Another painting, The Healer, further admits ambiguity between good and evil. It could show ripe bananas or another death by hanging.

With Ofili, a scandal still leads back to a big money gallery. Race and politics can make people uncomfortable, at least in America, but buyers have no trouble at all with rebels desperate to please, like Jeff Koons. Ofili is more eager than ever to claim the mantle of high culture, from ballet to Titian. Perhaps, too, he has lost the power of shock art along with the elephant poop. Perhaps he has lost the quality of a great physical comedian as well. Or perhaps controversy has helped hide his eagerness to please all along.

Ofili has long depended on a collision between form and content, like elephant poop and fine art. That collision has the potential to unleash new energy, but it can also wallow in rigid categories of form and content. The danger has always confronted the Young British Artists, like Mark Leckey, nurtured on their country's academic tradition, even as they rebel against it. The theatricality of Damien Hirst masks some rather ponderous intimations of mortality. Remember Andres Serrano, another object of Giuliani's anger? He has moved from Jesus immersed in piss to turds, even as Ofili has moved away.

Yet Ofili has moved away. With his move from London to Trinidad, he made at least the first step toward escape. One will just have to hope for more. He is still only a step away from simplicity and sentiment. At least for now, though, he has the installations, the collaborations, the color, and a greater agony. At least for now, too, a head of elephant poop is smiling on all that is to come.

Chris Ofili ran at the New Museum through January 25, 2015. His "Devil's Pie" ran at David Zwirner through November 3, 2007.