The Seduction of Modern Art

John Haberin New York City

René Magritte: The Seducer

"Surrealism," wrote André Breton, "does not want to be a new artistic school but a means of knowledge hitherto unexplored: the dream." René Magritte may seem to trace the course of a dream, but he makes dream interpretation dangerous to follow. In painting after painting, he also makes it dangerously seductive.

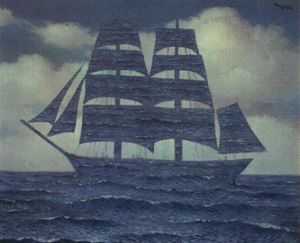

Consider in fact The Seducer, painted in 1950. No one would mistake it for an ordinary seascape. A ship floats alone on rough water, surrounded by one of Magritte's favorite motifs, clouds. Think of the idiom in English today, cloud nine. One has no indication of time, place, or the weather, no hint of sunlight or rain beyond the blue sky and stereotypical cumulus clouds. The sailing ship—of a kind once built for long ocean voyages—belongs to some unspecified past as remote and idealized as a manipulated dream world.

The dream

René Magritte spent most of his life in Belgium, but one will always remember him as part of the Surrealist circle. Like Salvador Dalí and Alberto Giacometti, he arrived in Paris in September 1927, almost four years after Breton wrote the first Surrealist manifesto. It was the very year of Breton's novel of love and dreams, Najda. He exhibited at the Surrealist Exposition that same year and, starting in 1936, in New York with Julien Levy, the movement's most important dealer.

He had little personal experience of the sea beyond dreams. He grew up almost dead center in Belgium, in a small town southwest of Brussels, where the plains of Waterloo start to give way to the hilly terrain of Mons. He returned from Paris to Brussels in 1930, pretty much for good. One could call him the perfect bourgeois, a role he loved to play in his art, although indications of an actual city appear as rarely in his art as anything else concrete.

Even back in the time of sailing ships, Belgium never rivaled its neighbors as a naval power. The Dutch, after breaking free of Spain, celebrated their ports in Baroque art, but not the Flemish. If Magritte ever felt the call of the sea, it had to mean a call within.

He has done something odd indeed to the ship: he has replaced its shape with an extension of the water. Surrealism celebrated just such illogical, uncanny juxtapositions. Breton liked to cite a writer calling himself Comte de Lautréamont, who in 1868 asked for an image "as beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella." One can think of the ship's transformation as a cut-and-paste job, and Surrealism has its roots, like pretty much all modern art, in Cubist collage.

If that leaves only a dream, the painting's title, The Seducer, also suggests uncensored fantasy, and Magritte himself spoke of painting not just real objects, as in a still life, but "real desires." Whoever is carrying out a seduction, no one is restraining his transgression. In French, seduction has connotations of pleasure and magic, and some critics have termed his art "magic realism"—and a precursor of the movement in America that spawned Philip Evergood and George Tooker. However, the seducer does not clearly appear. The pleasure seeker could be riding on the ship, painting it, or looking at it in the museum now. So could the one seduced—perhaps Magritte himself seduced by his own art.

In English, and Magritte did know English, seduction implies deception or trickery. One is seduced by the promises of a lover, a salesman, a politician, or an artist. If the painting first, then, simply piles on symbols of floating and pleasure, it also seems clearly designed to trick one into taking nonsense for reality. Just what is the sea doing up there with the ship, and what does this have to do with a human lover?

Unmooring

Maybe nothing. The Surrealists knew that dreams resist interpretation, which is why they liked them. However, Magritte pushes their illogic further, to the point that it questions naturalism and illusion in art. It may even question fixed meanings entirely. He juxtaposes two kinds of signs, the visual emblem and word seducer, and he detaches both from what they would ordinarily signify. If other Surrealists approach dreams as psychologists, Magritte gives the movement its linguistics department.

In perhaps his most famous work, the words This Is Not a Pipe hover beneath the image of a pipe. By unmooring language and representation from their usual function, he could be daring one to accept art and the mind as the scene of endless free associations, of perpetual free play. More frighteningly, he could be presenting the breakdown of meaning itself. One can take the marks of waves over the sails as an erasure, an insistence that this is not a ship. Either way, one cannot approach his art in the same way as older painting. One cannot pore over its perceptual cues in order to reconstruct the natural world or its symbolism to decipher a divine one.

Both alternatives, free play and a loss of meaning, remain pertinent. One can see The Seducer as carefully analyzing and displacing illusion. One can consider the water covering the ship as a reminder that, in a proper representation, an approaching ship would once have lain below the horizon. Besides, unmooring has its own connotations when it comes to the sea. Do these first two layers of meaning, pleasure and critical reflection on painting itself, contradict each other? Absolutely, and that already suggests a third, more unsettling level of interpretation, as a darker dream—one that many Surrealists themselves sometimes overlooked in his art.

The Surrealists never recognized Magritte as fully one of their own. For one thing, they distrusted trickery, even under the guise of toying with convention. For such a cosmopolitan circle, they talked about psychic automatism and a kind of primitive impulse underlying art. They did not like formalism, systematic investigations of language, or Magritte's seemingly conventional illusion. Conversely, they liked the literal, continuous three-dimensional space of Dalí's landscapes. How ironic (and delightful) that Magritte has lent himself to reinterpretation as photography, by Naomi White.

For another, they moved easily from desire to violence and from dreams to nightmares. Think of Giorgio de Chirico and his dark, empty streets, Dalí's swarms of ants, or his infamous watch melting over what may pass for a dead horse. Think of Two Children Menaced by a Nightingale by Max Ernst, with its open razor and the children fleeing in terror. Think of Giacometti's haunted Palace at 4 A.M., a confinement that Philip Guston must have admired.

For another, they moved easily from desire to violence and from dreams to nightmares. Think of Giorgio de Chirico and his dark, empty streets, Dalí's swarms of ants, or his infamous watch melting over what may pass for a dead horse. Think of Two Children Menaced by a Nightingale by Max Ernst, with its open razor and the children fleeing in terror. Think of Giacometti's haunted Palace at 4 A.M., a confinement that Philip Guston must have admired.

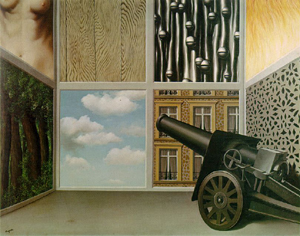

The Belgian may have seemed rather tame by comparison. In The Menaced Assassin, a woman lies naked with her throat cut, but the assassin still has time to listen to the gramophone. His likely abductors in turn wear middle-class suits and bowler hats. They satirize middle-class conventions savagely enough, and they suggest something fearful beneath, but they recognize them as part of life. When Magritte brings out the machinery of war, his cannon points hopefully On the Threshold of Liberty. For most Surrealists, taking liberties meant taking serious risks.

Not waving but drowning

Magritte survived until 1967, and the longer he lives, the purer and lighter his fantasies may seem to grow. Much of his best known and most challenging work dates from the late 1920s and the 1930s. After that, one sees simpler images—with a single subject, less text, and more and more of those clouds, as in The Seducer. In The Castle in the Pyrenees, from around 1960, a fortress perched on a huge rock floats far above the sea. One remembers the eerie poetry of The Empire of Light, painted in 1954, in which a night scene glows beneath a daytime sky.

However, Magritte's sensibility only appears weightless. Perhaps the dark fortress holds prisoners, and perhaps the entire jagged rock will crash to the ground. Perhaps the night scene means that dawn will never break, that no one can ever escape the nightmare. The Empire of Light could just as easily bear the title The Empire of Darkness. How would anyone know the difference?

The ship and water have the same ambiguity. Water could have floated above the sea, lifting the boat with it and changing a warship into a pleasure craft. Then again, the water could have swamped the boat and the faint outlines of people on it. Like the "chap" in Stevie Smith's poem, they could be "much further out than you thought, / And not waving but drowning." The call of sea includes the great sailing ships and the discovery of the New World, but also the lure of sirens. And you know what happened to those who listened.

Probably no other painting of his comes as close to monochrome, further obliterating the border between sea and sky. The wave crests may resemble the traces of a ship firmly scudding across the high seas, or they may look like treacherously choppy water during a storm. A variant dated three years later, now in a private collection, may incline more closely toward the first, the version in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts toward the second. With its typical lack of mission, the Guggenheim passed up a Magritte retrospective that stopped at SFMOMA in 2000, so New Yorkers may never know which of his manifold disguises represents him best.

Just as when he first shreds to pieces illusion and language, Magritte makes it impossible to separate comedy, poetry, illusion, and darkness. He can seem as literal as ordinary language, the kind that already uses "going to sea" as a metonym for sailing—and as paradoxical. He can make the rest of Surrealism, with its illustrated Existential crises, ponderous and philosophically naive by comparison.

The puzzling seducer may appear in name only because pleasure, much less love, is out of the question. In more than one early painting, lovers try to kiss, but with their heads covered in shrouds as if for a funeral. The most notorious seducer of all goes to hell at the end of the opera, but maybe, just maybe, Magritte's watery ship will continue on its course.

René Magritte's "The Seducer" (1950) is in the collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, a gift of Paul Mellon. If this essay approaches Surrealism from scratch, it began in discussion with a dear friend in the museum's docent program. I forced myself not to reread This Is Not a Pipe (1983) by Michel Foucault as I went, but I have probably borrowed from and mangled him unknowingly. A related article looks at what the Museum of Modern Art calls Magritte's Surrealist decade.