Bound and Gagged

John Haberin New York City

Desire Unbound: Surrealism

Surrealism set art free to dream. But is anyone in art still dreaming?

Art may lie in the doldrums these days, but one has to keep dreaming just to survive. And do not overlook a humble curator. A museum dreams of bringing past art alive—for a new time and a new place. It dreams of the latest blockbuster, a show so big that no one can avoid it. (I wanted to say "no one in one's right mind," but this is about Surrealism.) And, yes, even a scholar may dream about sex.

A gargantuan retrospective of the Surrealist movement goes for all three, but especially the sex. So why does it keep letting people down? Visitors keep telling me how petty it all was. Reviews have seen little in Surrealism itself but a historical aside, with few lasting images.

Perhaps, or maybe the blandness lies instead with the Met's relentless optimism. For all its uncanny size and by now familiar objects of desire, the show turns away from the period's strangest excesses. Surrealism confronted not just personal dreams, but art's worst nightmares, too.

Surrealism: the billboard ad

The Met evokes a Surrealism for today. Think of billboards in Herald Square—tawdry but arty, just a bit overblown, and totally conflict free. Like contemporary culture, too, it caters to male lust and to images of feminine beauty. But then, equally up to date, it still tries for gender balanced. And it ends with a surprise, Abstract Expressionism, as a climax of American Surrealism and to show Surrealism's relevance to the development of art ever since.

The show sure goes for the blockbuster, too. It promises three hundred objects, although that may count separately each scrap of paper in a Marcel Duchamp box. It ranges from painting to poetry and porn, although with a limited interest in experimental media and Surrealist drawing. With all the books and documents, many in French and barely within eye range behind glass, it dares one to take everything in. Even stripped down (not to make a pun) from London, where the show opened, it wants firmly to define a movement.

Above all, it has a single, central preoccupation—sex. I mean not just image upon image of desire, but also gossip about sex. The Met takes care to point out just who was sleeping with whom. That amounts to almost everyone involved anyway. Think of Jan Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp alone.

For all three reasons—relevance, scope, and sex—it rediscovers women in Surrealism. That means more, for a change, than as models and mistresses, perhaps alongside Leonor Fini or Meret Oppenheim with her fur-lined teacup. Instead of the headless body in front of the camera for Man Ray, Lee Miller appears with her own photography. I knew of Dorothea Tanning and Leonora Carrington more as names than as painters, Claude Cahun or a sculptor named simply Maria as not even that. The stare of Frida Kahlo fits well with a fresh attention to gender transformation, as in Duchamp's appearance in drag as Rose Sélavy. The last room reaches out to Louise Bourgeois after Bourgeois in painting but before her marble phallus, while stressing Peggy Guggenheim's role as dealer in the emergence of a new American sublime.

In all these ways, Jennifer Mundi of the Tate Modern creates a show of pleasure, breadth, and coherence, if not exactly thrills and chills. She starts more than a decade before André Breton launched the first Surrealist Manifesto, in 1924, with Giorgio di Chirico's neoclassic nightmares of empty town squares and onrushing trains. Besides a strict chronology after that—from Duchamp's Chocolate Grinder to Salvador Dalí and his late effusions—she has some splendid asides. One has Pablo Picasso and Alberto Giacometti, close influences who felt ambivalent at best about Surrealism. Just beyond lie Joseph Cornell with his boxes, a nice bridge from Man Ray's wit and delicacy to the show's close with more Americans. Hans Bellmer's photographs of tortured, oversexed dolls may never look as perverse, threatening, and fiendishly attractive.

She offers works that one might well never see. Duchamp's Sad Young Man on a Train, from the Guggenheim Collection in Venice, shows an elegiac, painterly version of Cubism. If anyone is sick and tired of melting watches, the show skips them. And in case one still fears bad vibes, exhibition placards supply quotes from Duchamp himself. When it comes to other artists, it turns out, he went in for some shameless boosterism.

Sex and other kinds of violence

Yet the show disappoints, big time. And the reason turns out to lie with all this good news. For all its scope and sexual candor, the exhibition has excluded the real naughty bits.

Sure, the political correctness beats Surrealism's wide male leer. I can live, too, without tales of Breton as Surrealism's pope and what a later show has called "Sixties Surreal." He excommunicated this writer or that artist, but the show's unflagging good spirits spare me the details. What I miss, however, is understanding why Jackson Pollock looks so startling and so right in that last room. Surrealism matters, because it brings together so many strands of Modernism's questioning.

With Cubism, art had seen reality not just reassembled, but in an act of self-destruction. With Expressionism, it had seen sexual and political rebellion living on the edge of bitter failure. And then came the twin traumas of World War I and Sigmund Freud. Breton faced both the mass hysteria and the personal kind, working with soldiers as a psychiatric aid. So in the safety of his home did Francis Picabia during World War II. And then with peace, things really got tough.

Surrealism emerges directly from Dada, an art in rebellion against the whole idea of art. At the Met, the second room moves quickly through those years. Dada appears there as one more preoccupation with sexuality and play. One gets the Sad Young Man and chocolate grinder. One gets Man Ray in his eggbeater, lost in the tracery of its shadows. Anti-art or conceptualism, much less the metaphysical still life of Giorgio Morandi, hardly show their face.

Surrealism's dreams of liberation extends to politics as well. Breton even visited Leon Trotsky in exile to plan a collaboration, and Max Ernst subtitled one painting Revolution by Night. At the Met, one gets René Magritte for his portrait head made of female private parts, but not the René Magritte with his cannon set On the Threshold of Liberty. One gets Woman with Her Throat Cut, but not The Palace at 4 A.M. In both, Giacometti's woman stands ambiguously for victim and for threat, murdered but reptilian, isolated and alone but stern and commanding. The palace, though, makes me think of the Spanish Civil War, already raging in 1932, and the lone woman comes to stand for an eerie combination of personal and political repression.

By displaying dreams in a waking world, Surrealism overturns consciousness as too many contemporary artists with dreamlike private visions often cannot. If art and understanding emerge somewhere between waking and sleeping, then what can anyone know—and how? At the Met, one gets di Chirico's train wrecks but not his Philosopher's Conquest or Metaphysical Muse. One gets puzzling images from Joan Miró, but not the larger, stained canvases like Birth of the World, with chance markings that so anticipate Jackson Pollock. One gets Magritte's This Is Not a Pipe, but on knickknacks in a well-stocked museum gift shop. I need those melting watches back after all.

Private lives

In each of these ways, Surrealism upsets the distinction between public and private. No wonder it influenced early TV. Desires spill over into art institutions and political ones, too. Imaginings never wholly one's own run riot over the conscious mind.

The world was making a distinction impossible anyhow. In 1927, a year before Breton's novel Nadja, Martin Heidegger unleashed existentialism. In Being and Time, consciousness does not exist apart from the Other and from "historical Being-in-the-World." Guillaume Apollinaire, the French poet, had coined the word Surrealism a decade before, the very year of the Bolshevik Revolution. Communism was to absorb, betray, and terrify Europe, sweeping artists and critics into its fervor. And it had a vision of mind, culture, and politics as inseparable.

Sexuality in Surrealism may start as a personal declaration. "As far as the eye can see," Breton wrote, "it recreates desire." Only desire never simply draws the line against impersonal forces. A steam engine barrels head-on into di Chirico's lust. A chocolate grinder turns sexual identity into one more commercial product for the machine age.

In Mad Love Breton imagines his past loves lined up like dummies in a shop window. They mock the supposed eternity of a new love—and, by implication, the pretensions of a fixed self with desires all to its own. "Because you are unique, you can't help being for me, always another, another you." Each person here has not a private life, but private lives. No wonder one identifies so well with Bellmer's puppets. No wonder, too, that Surrealism's Freudian overtones nurtured Pollock's Pasiphaë, born when Jung was in the air.

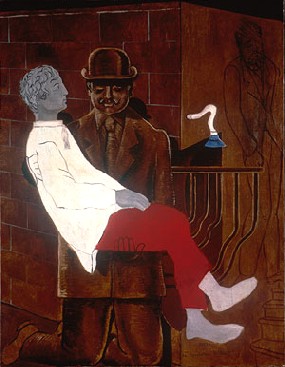

The Met has no patience for any of this. It has no room for an impersonal art, when it can trace art and character to self-expression. So much gossip about sleeping around makes the art into autobiography. In that Pietá, or Revolution by Night, Ernst combines personal history, a parody of faith, and night thoughts on a real revolution—with all the humor of Erzstbet Baerveldt's recent feminist meditation on the Pieta. The perfect bourgeois, nodding off beneath his bowler hat, holds in his lap a young man very much alive. The Met sees only Ernst's dislike of his father.

In one sense, the Met does get Surrealism right. It brings the period up to date, a goal shared by Sari Dienes or younger aspirants to a Surrealism today as well. Only one trouble. At the same time, it makes Surrealism seem old hat. No one here goes home saying, with Breton, "I want you to be madly loved."

Mad loves

Surrealism easily can seem quaint, like a bad art-historical detour. With Cubism and abstraction, Modernism tried one formal experiment after another. With a shift to New York in the 1940s, art slashed across huge canvases. In contrast, Surrealism's throwback to representation leaves rigid outlines and private, self-obsessed narratives.

In Surrealism, an almost incestuous Parisian circle tinkers with fine art. In photographs, its leading lights look like any prewar men's club—in their jackets, ties, and cute smiles. And certainly the art engages gender roles, even at its slyest, differently than Postmodernism. When Duchamp puts on a dress or Pierre Molinier gets even more unconventional, he does not stand outside conventions or accept their determination of his identity. Unlike even Cindy Sherman, he reshuffles them from within.

Surrealism does matter, though, and it matters because it does not follow the grand march of art history. In that history, Modernism has a nasty reputation these days. It can seem remote enough all by itself. Postmodernism sees it advancing in a straight line to a formalist utopia. One can think of it as idealistic, optimistic, male, and institutional.

Surrealism draws on so much of Modernism, but to tell a messier, even postmodern story. It projects quite another art history, one caught up in anxiety and distrust. This Modernism keeps struggling over gender roles, male attitudes, the inclusion of women, and institutional boundaries. It takes on poetry and the printed volume, because it unsettles the line between images and words, between the work and its total surroundings. It takes turns playing with beauty, hope, charisma, pleasure, and madness.

The Met has no room for anti-art or anti-anything else, because it is pro everything. That reinterprets Surrealism all too well for an age of mass markets and renewed patriotism. As in the show, sex these days is everywhere and yet more threatening than ever. Gender stereotypes have grown more rigid again, perhaps above all in explicit ads and movies, while the president calls for abstinence. In Breton's time, one would have called it the contradictions of capitalism.

Breton ends Najda with a demand: "La beauté sera CONVULSIVE ou ne sera pas." Beauty will be CONVULSIVE or it will not be. One needs a show with more convulsions.

"Surrealism: Desire Unbound" ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through May 12, 2002. A related review looks at "Surrealism Beyond Borders" and Surrealism in Mexico.