9.29.25 — Who Gets to Make Art?

He could be writing about a work of art or art itself. “I don’t have any answers yet,” and how could he? “The questions are too big.”

But no, Aidan Ryan is writing about his uncle and aunt, Andrew Topolski and Cindy Suffoletto, and their life in art, in I Am Here You Are Not I Love You (University of Iowa Press). What happened to Topolski, who others relied on as a teacher, who counted a Soho gallery or two among his supporters, who had precious materials and “technical precision”?  He emerged from Buffalo in the “Pictures generation,” only to become a footnote well before his death from cancer in 2008? What happened to Suffoletto, who set her own career aside for twenty years to manage him and his? How could she, and what allows anyone to persist in making art while others give it up without a trace? This is about two artists and his love, but also some “interesting moments” in late twentieth-century art—and it is the subject of a longer review in my latest upload.

He emerged from Buffalo in the “Pictures generation,” only to become a footnote well before his death from cancer in 2008? What happened to Suffoletto, who set her own career aside for twenty years to manage him and his? How could she, and what allows anyone to persist in making art while others give it up without a trace? This is about two artists and his love, but also some “interesting moments” in late twentieth-century art—and it is the subject of a longer review in my latest upload.

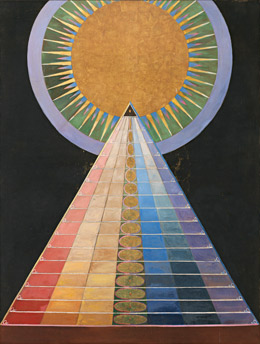

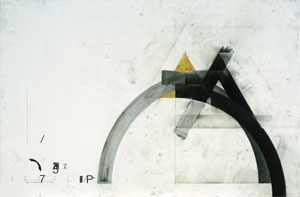

Maybe you never heard of either artist. I had not, and Ryan plainly intends the book as an act of recovery—not unlike another new book, by Pat Lipsky, from the same university press. A patron and friend saw Andy’s work as akin to music, while a later critic, who savored the geometry, heard the music of the spheres. Others found a dense, cool dialogue of words and images, an intertextualism. Cindy in color plates recalls Arshile Gorky—his gentle brushwork and tantalizing bad dreams. Were their most vivid imaginings no more than promises all along?

Ryan could hardly help seeing Andy and Cindy up close (and forgive me for switching to first names along with him). He knew her all his life until her death in 2012 and stayed with them in their final home, in the Catskills. “We swam in the Delaware, ate Cindy’s meals, [and] played in huge piles of leaves.” He cannot help it, too, because of how all three thought of themselves and their art. The book is about, first and foremost, individuals and individual moments—from the arts centers and antique shops of Buffalo to returning from lower Manhattan to Brooklyn on September 11. By the time it lists Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo, Charlie Clough, Nancy Dwyer, and Michael Zwack as “permanent members” of the “Pictures generation” from Buffalo, they have already exchanged glances going by.

No wonder it opens in the present tense, for these are present moments and alive, even if the artists have died. It starts at the end, Andy struggling merely to snap a picture, while Cindy “does the lifting—tugging, stutter-stepping to clear a space.” It shifts to the past tense for the rest, but you may hardly notice the change. Even in the past tense, the fatal onset of Cindy’s lung disease comes as a terrifying moment in the present. Text is lyrical, too, and I am having trouble not simply quoting, leaving the narrative to them. Like fires on the horizon, life is something “we expect but never see coming.”

As a professor told Ryan, “we remember . . . not what people . . . did but what they made us feel.” He took it for a cliché but, he adds, he should have seen it as a warning. While modest in length, the book has more details than you may wish to know, but no shortage of feelings. It is the author’s story, too, as he matures into a writer, editor, and musician. It all ends pretty much where it began, with death and dying—and the note found in Cindy’s studio that became the book’s awkward title. That and the sting of a survey of the “Pictures generation” at the Met that left Andy out.

The book shines in fleeting moments, but it sees them as “opening onto a much wider world” of people and controversies. Did art in the 1990s sell out to commerce? Art for Andy was always a commodity, like the antique stores in Buffalo that fed it, and what commodity is more precious to an artist than time? Dealers and collectors are mostly admirable, even when they don’t know their own tastes, and Jean-Michel Basquiat is downright innocent. It is also a picture of what mattered personally to a generation known more for a brutal irony. Systems are fine, Andy would say, but “ideas are not art.”

It is a picture, too, of the art worlds that Andy and Cindy inhabited—although it must omit others in the movement, like Barbara Bloom, from the West Coast. How did Buffalo become home to the Albright-Knox (now Buffalo-AKG) museum, with Nelson Rockefeller (before his gift of African art to the Met) on the board and an awesome collection of modern and postwar art? How did institutions like the University of Buffalo and the Essex Arts Center nurture contemporary talent? (Hint: “you can do it with us or you can do it all on your end.”) Why did young artists then leave for New York City? Was it all to show at Metro Pictures, to enjoy Williamsburg rents, and to party at the Mudd Club? And how did Andy end up making furniture and woodworking in a village upstate?

It is a picture, too, of the art worlds that Andy and Cindy inhabited—although it must omit others in the movement, like Barbara Bloom, from the West Coast. How did Buffalo become home to the Albright-Knox (now Buffalo-AKG) museum, with Nelson Rockefeller (before his gift of African art to the Met) on the board and an awesome collection of modern and postwar art? How did institutions like the University of Buffalo and the Essex Arts Center nurture contemporary talent? (Hint: “you can do it with us or you can do it all on your end.”) Why did young artists then leave for New York City? Was it all to show at Metro Pictures, to enjoy Williamsburg rents, and to party at the Mudd Club? And how did Andy end up making furniture and woodworking in a village upstate?

The book is full of questions, as promised. Was his loss of stature and sales just the times—or was it the clash between critics like myself, who put art into words, and art, which surpasses the limits of my language? All well and good, but then no artist would have a chance. Is it all luck, or did his work fit uncomfortably between surface beauty, “Pictures” irony, and the “sensibility of a machinist”? Why did Cindy sacrifice everything for her art—and then, like Lee Krasner for Jackson Pollock, sacrifice her art for his? “She lets him help her move the armchair from its spot against the pale plaster wall,” and soon both are gone.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site. I do rely as much as I can on the book’s language, with minor edits to fit