10.30.23 — The Game of Painting

A show for Helen Marten is either a triumph of abstract painting or a game. Either way, a voice explains, it is “conquerable resistance,” and how can you resist?

Evidence of Theater weighs the evidence, with enough theater to confuse anyone. Her images hold out plenty of temptations, from cute little animals to breakfast cereal and a game of chess. Still, she has her devotion to painting. So which gives her work credibility, painting or the game?

Maybe abstraction was always a game. Postmodernism could point out the rules, in the spirit of seeing through them, while formalism could insist on them. And the game played out on a huge scale, in Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism. Marten herself has both floors of a gallery, at Greene Naftali through November 4. The ground floor alone has space for a dozen large paintings, which morph upstairs into video. In place of a press release, your only guide is a personal essay, with due reference to Roland Barthes. “The fundamental structural agenda of evidence is scattered,” she admits, “but it has rhythm and logic.”

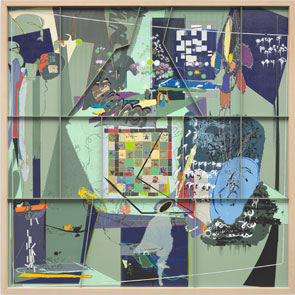

It also commands space, with (as the rules of Modernism go) art as object. Framed panels hang in larger white frames much like partitions, at all angles to the paintings and the walls. One rests on the lower white frame and the floor. Elements of sculpture and assemblage take them further into space. Most have a proper grid, as both an overlay of wood and a painted one. That still leaves space for savvy gestures, splashes of color, and cryptic symbols.

Still, is it only a game? The permutations suggest just playing around, and painted grids do look like chessboards. Physical chess sets appear, too, with abstract, unconventional pieces. They get along easily with a standpipe, a work desk laid out as a kitchen table, and much else. Marcel Duchamp, the ultimate modern chess player, would approve. And then there is the ultimate refusal of fine art’s game, Kellogg’s Corn Flakes. Was this Pop Art all along or just a more detached and devious game?

In prints within a panel, the cereal box and a corn flake rest in the hand of a smiling character with a striped suit, a white beard, and a preposterous handlebar mustache. Is he a product spokesperson, like Colonel Sanders, or a skeptic? Text in those prints gives the words of a psychologist, even as the person at hand keeps his mouth closed. “You can test reality,” says the psychologist, where “you” could be either the consumer or the product developer. There is always the taste test. There is also, he insists triumphantly, that conquerable resistance.

He is not the only judge, quite apart from you. Once a figure in black robes takes his place, and once the painted image of a man leans forward, anxious or lost in thought. The more you look, the more others multiply, too, including (a title has it) “good judges.” I do not believe they are the Bible’s twelve judges of Israel. Is it hard evidence or theater? The Old Testament god has nothing on the demands of “theory.”

For all that, painting rules if you let it. With such artists as Cecily Brown and Amy Sillman, the fluid space between abstraction and representation has become the norm. Quite apart from painting, Buckminster Fuller called one project The World Game, without a trace of cynicism. At stake in the game was the planet. What is at stake here is harder to say, and it may depend on whether you look at the big picture or up close for details—and on just how much Colonel Kellogg’s gets on your nerves. For now, like Oscar Wilde, I can resist anything but temptation.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.