4.19.24 — Birthing Feminism

Judy Chicago ends her retrospective with other women. It could hardly be otherwise, when her best-known work, The Dinner Party, relied on the assistance of four hundred. With its place settings for thirty-nine more, it sought to span recorded history as well.

No surprise, then, if she devotes a full floor of her retrospective to women across the centuries and across the arts, at the New Museum. It could hardly be otherwise, when she titles it “Herstory,” through March 3. And yes, it is shameful that I am posting this late, but at least the review in full was always online.

For her, a women’s history is not just recovered but created again each time, and so is art—not as a male saga of lone genius, but as a collaboration. She reserves a place for goddesses as well as humans as well. She keeps coming back, too, to acts of birth. Will women still recognize it as their own? I have my doubts. If you ask me, art and activism need not more primordial women, but fewer male gods.

For her, a women’s history is not just recovered but created again each time, and so is art—not as a male saga of lone genius, but as a collaboration. She reserves a place for goddesses as well as humans as well. She keeps coming back, too, to acts of birth. Will women still recognize it as their own? I have my doubts. If you ask me, art and activism need not more primordial women, but fewer male gods.

New York was not new to her in 1980, when The Dinner Party reached the Brooklyn Museum. (It later found a permanent home at the museum, as anchor to its Sackler Center for Feminist Art.) She and her first husband had hitchhiked to New York in the 1960s, living briefly in Greenwich Village. Still, she felt new to New York. She left a personal stamp on feminism, one that not everyone could accept but many have loved—one rooted in primordial beings and present-day sex organs. For a fuller answer, I work a longer version of this review together with a recent earlier report on Shahzia Sikander as my latest upload.

I have my qualms about questioning either one. It aligns me with conservative critics like Hilton Kramer of The New York Times, who trashed her back then along with pretty much all postwar American art. It puts me, a white male, in the position of speaking for feminism when I hope to support it. And Chicago’s retrospective does offer a greater diversity, including the glassware, ceramics, and embroidery of those place settings. She deserves credit, too, for founding the Feminist Art Project at Cal State Fresno and later, with Miriam Schapiro, at Cal Arts. Still, whatever her history or herstory, she is always at its center.

Banners hang over The City of Women, that floor-scale installation, with one in particular flying high, What If Women Ruled the World? And here they do rule, but at a cost. You will spot paintings by Hilma af Klint, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, and Georgia O’Keeffe, amid less-compelling models for Symbolism and Abstraction. You will spot those who refuse to be reduced to “significant others,” like Dora Maar (for Pablo Picasso), Frida Kahlo (for Diego Rivera), Leonora Carrington (for Max Ernst). You will spot Käthe Kollwitz next to Martha Graham, with an eye to how women pose, and painters near books and photographs of writers, with labels you may never find. For all its wonders, it eradicates differences and reduces everyone.

Even so, Chicago keeps demanding more. She took the Feminist Art Project seriously. Her classes became Womanhouse—collaborations with her chosen students, with their everyday lives as performance art, and she credits the resulting film and photographs to them and not to herself. She does not abandon spray paint and lacquer, now on vinyl on canvas. Still, in adopting a radial motif and at times ceramics, she is well on her way to the strengths and weaknesses of The Dinner Party. I may not like it, but it anchors the Sackler Center and the feminist revolution to this day.

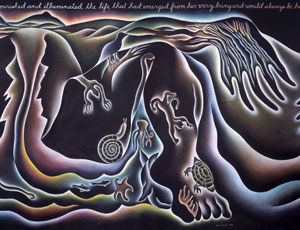

Embroidery and collaboration carry over to the Birth Project of the early 1980s, with at least one hundred fifty women to execute the needlepoint. Colors darken, but not for long. Men get their project, too, but with articulated musculature and grimaces that had me grimacing as well. Still, she adopts the translucency of stained glass for her Rainbow Shabbat of 1992. She also collaborates with her present husband, Donald Woodman, on a larger Holocaust project and, in New Mexico, a co-ed follow-up to Womanhouse. Women’s roles have become gender roles in a racially torn America.

Chicago gets all three principal floors, including the last for her city of art and women. If you happen to begin there, so much the better. It makes clear how much her hopes do not depend on birthing. She herself never bothered with motherhood. As she told The Guardian, “There was no way on this earth I could have had children and the career I’ve had.” Her work is still tacky, sentimental, and reductive, but she gave it her all.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.