12.18.23 — An Airman Foresees his Death

Michael Richards spills out from a museum’s front gallery and into the lobby. He can hardly help himself, as an artist whose work never could decide whether to take flight or to fall.

Still, his show stops there, and the ampler south gallery at the Bronx Museum remains dark, which seems only right. Richards died far too soon—old enough to have found himself, but never to discover where it would take him. It gives his imagery of flight and the human body, often his own body, a greater poignancy.  Yet there is only so much to add to a 2016 retrospective on Governors Island. There is only so much, too, that I can add to my review then. Forgive me, then, if I repeat it here, with due updates.

Yet there is only so much to add to a 2016 retrospective on Governors Island. There is only so much, too, that I can add to my review then. Forgive me, then, if I repeat it here, with due updates.

When an artist dies young, it may do more than cut short a career. It can freeze that career into a single image, where the art would almost certainly have moved on. For Richards, that image has come to commemorate his death, as if he had been preparing for it all his life. In sculpture, Richards himself stands just off the ground, arms by his side as if immobilized, palms raised in supplication or in hope. He bears the burden or the empowerment of a pilot’s full dress, right down to the straps across his chest that both grant him a parachute and hold him in place forever. I thought of a poem by William Butler Yeats, “An Irish Airman Foresees His Death,” only Richards was an African American from Brooklyn and Jamaica, the home of John Dunkley, with additional roots in Costa Rica.

Gilding lends the sculpture both the tackiness of pop culture and a greater glory. So do small fighter planes, like a child’s toys, assaulting his body from every side. He has any number of echoes in Renaissance painting, as Saint Sebastian pierced by arrows. He could be plummeting to the earth or rising into the heavens, and Richards himself spoke of “the idea of flight” as that of “being lifted up, enraptured, or taken up to a safe place—to a better world.” He seems to speak for all the lives lost in the Twin Towers, like so much art after 9/11 in memory of disaster. Only he made the sculpture in 1999, and he died that awful morning in Tower One.

He still has a few tricks up his sleeve, through January 7. Others have riffed on the first Christian martyr as well, such as Juan Francisco Elso, Antony Gormley, and Chris Ofili, who convert the arrows into spikes or nails. Richards, though, does not settle for either self-aggrandizement or martyrdom. His title, Tar Baby vs. St. Sebastian, shows an awareness of Judeo-Christian tradition, but also of stereotypes and folklore closer to home. Of course, the arrows did not kill the saint, who was then beheaded, and those who tried to pummel the tar baby found themselves stuck. In other sculpture, the artist’s forearms become wings, pierced only by feathers—and in one those feathers, motor driven, get to wriggle.

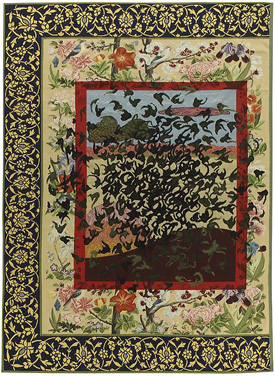

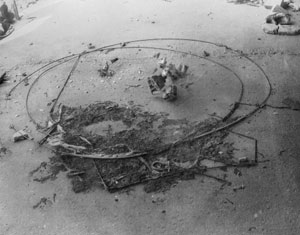

The pilot’s uniform, like much of his art, points to the Tuskegee airmen, the first African American military pilots. And Richards sees that segregated unit, too, as at once empowered, ignored, and in danger. In Air Fall, planes dive toward a mirrored target, covered in artificial hair. The same black hair gives a row of helmets the look of fur hats for a long Siberian winter. Drawings invoke the fall of Icarus, the doomed subject that everyone sees fit to ignore for Pieter Bruegel. They offer “escape plans,” but on the order of a mere ladder and a grave of chicken bones held together by watermelon glue.

For Richards, death at age thirty-eight came close to aborting his career entirely. He did not flame out in the public eye like Jean-Michel Basquiat, and he has not had much attention since. A retrospective on Governors Island and a later one at the Bronx Museum promise to help, but only barely. Little more than a single room in each limits him to a few works and fewer themes. Screen captures suggest other interests, with allusions to the Middle Passage, Al Jolson, and “Let Me Entertain You.” Yet the videos do not appear, and the limits could well be his.

At least the sponsor of the first show, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, makes an effort and recovers a bit of history, while the Bronx adds a fascinating record of his early years in performance. LMCC’s “River to River” weekends have largely omitted art, and its exhibitions have left Lower Manhattan behind. Once, though, it had residencies on the ninety-second floor of the World Trade Center, where Richards spent that fateful night. Artists are not supposed to sleep in their studios, but he wanted to continue to work and to have that view of heaven. As another sculpture puts it, of faces smeared with black, A Loss of Faith Brings Vertigo. One can never know whether he had more in him, but one can see him at work on the myth of the overturning of myth.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.