12.15.23 — What Is Left to Ask?

To wrap up from last time on fall New York art fairs, does New York need another art fair—a photography fair at that? Now it gets one.

Each spring, the AIPAD Photography Show already makes a case for photography as art. Work there falls safely within the bounds of fashion photography and the perfect moment, while the subjects of documentary photography all but beg for admiration and sympathy. Photofairs New York means to change that. The frankness of Robert Frank,  the irony of Lee Friedlander, the detachment of Stephen Shore, the shock of Robert Mapplethorpe or Peter Hujar, and the intimacy of women among women still seem worlds away. In their place, though, comes a broader and less settled view.

the irony of Lee Friedlander, the detachment of Stephen Shore, the shock of Robert Mapplethorpe or Peter Hujar, and the intimacy of women among women still seem worlds away. In their place, though, comes a broader and less settled view.

Taken together and aisles apart, Howard Greenberg and Robert Mann galleries pull off a respectable survey of photography, as one should expect. After that, better think again. At the other end of the Javits Center from the Armory Show, Photofairs invites galleries not devoted to the medium, and the disjunction helps. Rodrigo Valenzuela (with Asya Geisberg) creates a landscape from studio debris, while HackelBury London displays artists associated with anything but photography, the Starn Twins. Media strain, too, to fit the formula, like video from Huntrezz (with Transfer). As you walk alongside, you see yourself, but with additions that you may not recognize as yours—just as she herself hopes to escape conventions regarding private and social identity.

ClampArt, too, can be counted on for gender bending, while shoppers for Catherine DeLattre (with Osmos) could almost be faking theirs. More generally, if the fair has a heart, it lies in a contemporary surrealism, with surreal lighting to match. Ole Marius Joergensen (with Momentum) takes one into Miami at night, while Amanda Means (with JHB) photographs the lighting itself. The approach can allow portraiture to acknowledge the viewer’s gaze and to look back, like that of Kristine Potter (with Sasha Wolf). Subjects for Merik Goma (with Management) may instead look away, through the darkness and into the light. As a title puts it, Your Absence Is My Monument, but your presence is everywhere.

What is left to say or to ask about the Armory Show? Who will exhibit? Pretty much everyone, now that some dealers feel obliged to show both here and at an alternative fair, and that has me worried. What artists will they bring with them, and how will they look in a convention center? Again, pretty much everyone, in booths that offer more space than many a gallery. And not just younger galleries with their own section of the fair.

Can any artist stand out these days, or must you pick your own winners, if you dare? A section for solo artists makes, if anything, the least impact. What, then, for this year’s theme? A section for material histories sure sounds in line with today’s revival of thread, ceramics, and craft—and a layering of clay on fabric by Remy Jungerman (with Fridman), from Suriname, makes its heritage and its flatness palpable. Still, any and all work has its media, and the theme can excuse anything. It left me glad to retreat to the fair’s long central island with its comfortable seats, a champagne lounge, and a dozen sculptures and installations.

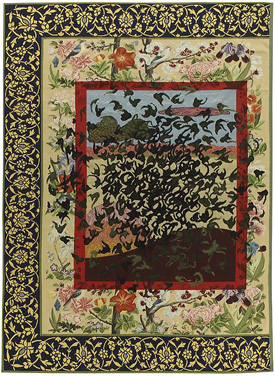

Yet they, too, play to collectors and the crowd. Shahzia Sikander and Yinka Syonibare have their earthly godesses, Xu Zhen his cross between the Greek god of victory and the Buddhist protector of lost souls. Hank Willis Thomas has his silvery striker and Pae White the softer shine of her curtains. I preferred the closeness to death of Agnes Denes in her nineties, with skeletons in the acid pink of an airless glass box. What then is left to say about the fairs—or the business side of art? Better return to the galleries and wait until next year.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.