1.17.24 — The Oldest and the New

In October 1849, a smart young Parisian set out to see the world. Then twenty-seven, Maxime Du Camp got himself a camera and learned to use it from the best of the best, Gustave Le Gray.

Then he grabbed a close friend, Gustave Flaubert, and headed for Egypt and the Middle East. He returned after a year and a half with two hundred negatives of pyramids, ancient temples, mosques, and now and then signs of life. The oldest of the old and the newest of the new,  in technology and in art—what could better suit a man confident in his talents and eager for attention. He might not mind one bit to see it all again as “Proof: Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa,” at the Met through January 21, and I work this together with an upcoming report on the ancient Near East, Byzantine art, and Africa as a longer review and my latest upload.

in technology and in art—what could better suit a man confident in his talents and eager for attention. He might not mind one bit to see it all again as “Proof: Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa,” at the Met through January 21, and I work this together with an upcoming report on the ancient Near East, Byzantine art, and Africa as a longer review and my latest upload.

What, though, was Du Camp after, civilizations or something larger than life? What, for that matter, was a camera to him, the latest art form or a tool of scientific clarity? He had no shortage of support for them all. He had the encouragement of France’s Minister of Public Instruction, who urged him to remember photography’s “uncontestable exactitude.” Once back home, he got to work with Blanquart-Evrard, France’s first commercial photographic press. Its crisp, cool shades of black and white echoed both that exactitude and a popular art form, lithography.

But then why choose? Just a generation after Napoleon’s aspirations to empire and so soon after the invention of photography, the pyramids and the camera alike still felt novel and still inspired awe. Critics dismissed the prints as “vaporous” or derivative of contemporary prints, but the public disagreed. A publisher selected more than half the images for a book, Egypte, Nubie, Palestine, et Syrie—the first in France with photographs as illustrations. Du Camp’s career as a writer and journalist was off to a good start, and he never looked back. He traded the camera for a decent sofa.

Not that everything went smoothly. Chemical salts on paper negatives could not stand up to a long journey and desert heat. Fortunately, the same wet treatment that produced those cool tones also revived the negatives. Fortunately, too, they did not stop Du Camp from making his own “proof prints,” possibly in conjunction with Le Gray. They have entered the Met’s collection, which naturally prefers them. It relishes the greater warmth of their pale yellow-gray.

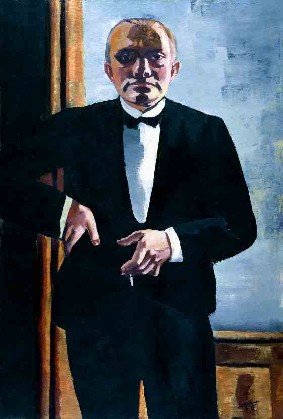

You can decide for yourself, for the museum displays both versions of quite a few. I like both the sharpness of black and white and texture in yellow-gray skies—even while knowing that they may have come about in the darkroom by smearing more chemicals over the skies to remove signs of contemporary life. The exotic for its own sake was just too appealing for Du Camp to pass up. People appear only as props to set off the amazing scale of temples, pillars, statues, and windswept sands. Flaubert himself shows up just once, and he seems to have slouched onto the scene rather than posed for the camera. The novelist had his own uncontestable exactitude in prose, but Du Camp never so much as mentions him in an account of their journey.

Not that the Met withholds criticism. It sees the photos as condescending to a foreign culture, but I am not so sure. If anything, Du Camp seems largely indifferent to culture, whether ancient or Islamic. The show has just a few prints by others, and he just cannot match them. They bring their structures closer to the viewer, for a sense of art and life. He has something else in mind—density, detail, and mass.

He likes a residential neighborhood in Cairo for its balconies and box-like gardens, not its inhabitants at work, at prayer, or at play. He likes scenes divided between bulky structures and utter ruins, but without a moral. He likes to center a panorama on an ancient dome or minaret, but they pop out of nowhere, more as landmarks than signs of foolishness or faith. One might never know that anyone saw the Middle East as a holy land. As he travels down the Nile to what was then the Nubia, in present-day Egypt and Sudan, he finally gets fully into ancient ambitions, but he wants them all for himself. He alone holds the proof.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.