1.31.24 — Two Imperatives

I shall never forget the great age of postwar abstraction—and a pressing need for diversity. I sought out abstract painting when I began this Web site nearly thirty years ago, from the Upper East Side to Staten Island. And I keep returning to galleries that recover women artists from a time when they thrived, suffered neglect, or both.

Could, though, those imperatives collide head on? At least one Chelsea gallery thinks otherwise (and apologies that my obsessions so often bring me there). It opens the new year with women who endured, as “Perseverance,” at Berry Campbell through February 3.  The show cannot avoid colliding with itself, but you can feel the impact in your gut. It is also just part of the give and take within abstraction today, and I round out the story next time with Zipora Fried just a few blocks away, as also part of a longer review and my latest upload.

The show cannot avoid colliding with itself, but you can feel the impact in your gut. It is also just part of the give and take within abstraction today, and I round out the story next time with Zipora Fried just a few blocks away, as also part of a longer review and my latest upload.

But does it bring what you could never have seen when the work was made—or just another day in the galleries? You know the narrative. A world war brought artists to America and unleashed the pent-up energy of New York City. (Not all that long before Mark Rothko created his dark or luminous abstraction, he painted the subways.) Yet it brought, the story continues, a stifling uniformity. Postmodernism and critical theory spoke often of hegemony, a white male hegemony.

Stories come all too easily. What if there were no typical days in the galleries? Most were showing other things entirely, like portraiture and prewar art. Others were moving on to challenge abstract art—in the name, at times, of its hottest stars and guiding lights. When it comes down to it, the narrative reads today’s scene into lonelier days. Who back then could have imagined countless art fairs, endless money, and the dull uniformity that they, too, so often demand?

The dealers behind “Perseverance” do their best to keep up while looking back. Both are women, but then so were Betty Parsons and Peggy Guggenheim, who encouraged Jackson Pollock to break, literally, through old nostrums and new walls. They include the occasional younger artist, like Susan Vecsey, whose colors of sky and sea bring out the vertical weave of linen. They cannot make space for more self-reflective styles bubbling up when, wise men insisted, painting was dead. But how could they, without spoiling a show of women under the influence? I had to go to Staten Island in the 1990s for the sequel, to Snug Harbor, before a still more eclectic view of abstraction took over in Brooklyn, on the Lower East Side, and in Tribeca today.

The collision of ideals remains. Do these artists bring a near uniformity of gestures or something else again? Were they neglected because they accepted the hegemony, at the cost of originality, or because they refused? Postwar art itself was about the refusal of uniformity, and that brought contradictions, too. It called for not just gestures but signatures, like drips and floating rectangles. Is that because signatures help art stand out—or because they make it easier to sell?

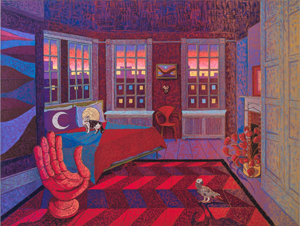

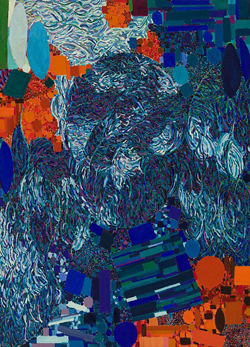

The most memorable painting in “Perseverance” gets along just fine without a unique motif. Gesture for Perle Fine and Sonia Gechtoff brings a depth of color on a grand scale, and Judith Godwin calls her explosive gestures Wham. Not that a more obvious focus is altogether absent. Vivian Springford surrounds fiery pinks and yellow with a loose dark circle, like a nova, while more bright stains spread outward. Alice Baber piles on loose circles of color beneath her white ground, like a lonely crowd. There is more to art than making history.

The show has familiar names here and there, like Lynne Drexler and Helen Frankenthaler, neither with major work. Others seem largely indifferent to standing apart. Mary Abbott and Ethel Schwabacher set their forms in depth in wide-open fields of color that recall Arshile Gorky. Dorothy Dehner gives the steel of David Smith the dignity of true sentinels, while Claire Falkenstein treats his sheet metal, suspended within a cube, almost like tissue paper. If this is derivative, so be it. Connections were what gave the New York School its life.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.