2.14.24 — Too Many Suspects

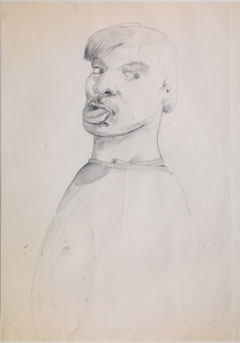

Stéphane Mandelbaum died at just twenty-five, in 1986, of a hit job. Yet his life was only as messy as his art, at the Drawing Center through February 18.

If his retrospective were a crime novel, there would be all too many suspects. The curators, Laura Hoptman and Susanne Pfeffer, speak discretely of a criminal syndicate, but he himself barely skirted the law. He trafficked in the black market for art and got caught trying to steal a work by Alberto Giacometti.  He hung out in all the wrong places, only starting with clubs and cafés in Brussels. The dark night scene in Montmartre for Pablo Picasso seems tame by comparison. His drawings themselves bear damaging testimony.

He hung out in all the wrong places, only starting with clubs and cafés in Brussels. The dark night scene in Montmartre for Pablo Picasso seems tame by comparison. His drawings themselves bear damaging testimony.

They start with fellow denizens of that scene, with unfailing sympathy. It extends to young white men and black women in racially charged surroundings. Titles identify them by first name, because his art was on a first-name basis with everyone. He calls them collectively Lolitas, with the humor turned at least partly on himself. His pencil swoops casually across the page, staking out faces and poses alike in its long traces. He works fast, and there is no going back.

Mandelbaum drew what haunted him. That, at least, is a given for a compulsive artist, but it raises more questions than it answers. He drew what he loved, in faces out of his favorite haunts and dearest imagination. He drew, too, what he hated and feared. But which was which? What were his nightmares, and what were his dreams? An artist who blended self-portraits with Nazi imagery may not himself have known.

Who can say what he left to his fevered imagination? Raised as a Jew, Mandelbaum heard of the Holocaust from a grandfather who survived it in Poland and whose brothers did not. A book, a gift from his father, helped him follow that family history, but in reverse, like a personal journey into the past. Its title says it all—Souvenirs Obscurs d’un Juif Polonais Né en France, or “Dim Memories of a Polish Jew Born in France.” A series of drawings takes off from the book, by Pierre Goldman, but with embellishments. He cannot disentangle observation from confession and confessions from nightmares.

He draws Nazis like Ernst Rohm and Joseph Goebbels, the latter in the midst of a terrifying speech that Mandelbaum could never have heard. He draws the filmmakers he admired most, including those he could never have met. Naturally they, too, made their name with subject matter on the edge, like Pier Paolo Pasolino, Luis Buñuel, and Rainer Werner Fassbinder. He draws Arthur Rimbaud, the poet, dressed for a rendezvous in cold weather. He sketches Francis Bacon, whose insistence on finding character in the cut of a face anticipates his own. He leaves open, though, what counts as realism and what as distortion, as Bacon never could.

A solo show extends from the main gallery to the smaller one behind it, and the ample space only raises more questions. Just what kind of artist was he—an outsider before outsider art entered the mainstream, the graduate of a proper arts education, or a willful heir to Bacon? After the café drawings, he crowds more and more onto a sheet. That includes text fragments that are all but illegible, collage like the face of a Nazi on a porn star, a self-portrait as Geule Casée (or “Broken Face,” only more vulgar in French) and swarms of pen marks like armies on the march. He may never earn a greater reputation outside Belgium, but he provides testimony to a fatefully short life. The real killer may have been the twentieth century.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.