3.1.24 — Sailing to Byzantium

Late in the tenth century, a Nubian wall painting shows an imposing figure in priestly robes backed by a still taller one. It is Bishop Petros protected by Saint Peter, his namesake. No surprises there, but for one thing: the bishop is black, for Nubia spanned today’s southern Egypt and the Sudan. Peter, in turn, is white, for the Christianity of the Roman Empire had extended its reach to Africa, even as Rome had fallen long ago.

With “Africa and Byzantium,” the Met takes a fresh look at the Byzantine empire that emerged from the division of Rome’s in 395, but with the cracks showing at least two hundred years earlier. Here it no longer centers on Constantinople, or Byzantium (today’s Istanbul) on the Bosporus Strait connecting Europe and Asia. It looks south, to Syria, and then west across North Africa from Egypt to Algeria— and further south to present-day Sudan and Ethiopia, through March 3. Nor is it the place where painting has gone to die, in the “dark ages” between classical art and the Renaissance. It is open-minded and eclectic, a model for diversity in art now. It is where at least four major religions met, fought, and reached an ever-changing agreement.

and further south to present-day Sudan and Ethiopia, through March 3. Nor is it the place where painting has gone to die, in the “dark ages” between classical art and the Renaissance. It is open-minded and eclectic, a model for diversity in art now. It is where at least four major religions met, fought, and reached an ever-changing agreement.

William Butler Yeats in “Sailing to Byzantium” had it wrong. This is a country for old men (and women), with a respect for authority and antiquity. More than a hundred years after Saint Peter, Jesus looks after a Nubian dignitary. The two wall paintings are so alike in style and dimensions that they could have been painted together. These really are “monuments of unaging intellect,” but an intellect that accommodates Christianity, Roman gods, the Coptic culture of Egypt, and Jewish scholars in Alexandria and Tunis. Nubian armies repelled Islamic invaders, but by all means throw the Koran into the mix.

To ask the Met, histories of Western art have had it wrong, too. Byzantine art may have you thinking of Madonnas, where the child gestures regally but stiffly and well-articulated folds in her black robe only bring out their flatness. Gilding makes them look that much more inert, and the harsh outlines of their features make them look as if they were squinting. And sure, many such icons appear here, but in an open, fluid history. Rather than a sudden turn from classicism to darkness and back, it presents a continuing narrative connecting and explaining them all. It has room for blackness, too, although the ultimate authorities are white.

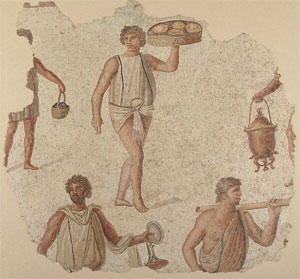

The show opens with mosaics, in a firmly classical world. Their pale colors have all the brightness of ancient Rome, with well-articulated figures in wide-open spaces, stretching their limbs as they prepare for a feast. Then come small jugs in African red clay, in the shape of heads with whimsical faces, and bowls, a lion, and a dolphin in clear rock crystal. The sheer variety of media stands out, as does the debt at once to Rome and Africa. Jewelry, textiles, and carved boxes for precious possessions confirm the picture. The bronze bust of a crying child picks up where the red clay left off, but with the poignancy of being young, helpless, and black.

A textile shows Greek or Roman gods, but also black. Do not be surprised either if similar figures appear to either side of a Madonna and Child. What religion is this, and which myth is which? Here Christianity claims everything and anything for its own. The flattening comes soon enough, but its disrespect for naturalism allows other liberties. Why stop with an icon when you can throw in as many Biblical or folk anecdotes as you like? The heads of apostles as oil lamps run to further whimsy, even as the icons deny it.

How good is this history? I am well outside my expertise. As with shows of early Buddhism and women of Mesopotamia, I may not contribute something beyond a recommendation the way, I have argued, a critic should. I can only share my personal encounter, from the perspective of European and contemporary American art—including art that itself journeys to Africa. Bear in mind, too, the Met’s nasty habit of presenting a curator’s minority interpretation as law. In shifting the focus to North Africa, has it left both Byzantium and African art behind?

It is fascinating all the same, and the many languages on display make a strong case as well. The curators, led by Andrea Achi, get to ask if you knew that Sudan has more pyramids than Egypt. The last room throw in a few living artists who respond to tradition with pattern and decoration. Given museum trends toward making everything about contemporary art, I can only be grateful that there are not more of them. Think of the exhibition as not history alone, but also an ideal. I can live with that, a white lie, and a black Artemis.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.