4.3.24 — Demanding the Visible

Is blackness invisible? Maybe literally so, and maybe so for African Americans everywhere who ask to become fully visible to white eyes.

The twenty-eight artists in “Going Dark” demand to be seen—not as targets for the police, but as individuals with human needs. They demand to be seen as artists, too, shaping what it means to be an individual. Much the same demand underlies the electrifying opening of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man as well,  and several here take its title for theirs. Still, the show’s title continues, this is “The Contemporary Figure at the Edge of Visibility,” and every one of them contributes to the darkness. Just how they seek invisibility is more than half the point. That alone keeps the show compelling the full length of the ramp, at the Guggenheim through April 7.

and several here take its title for theirs. Still, the show’s title continues, this is “The Contemporary Figure at the Edge of Visibility,” and every one of them contributes to the darkness. Just how they seek invisibility is more than half the point. That alone keeps the show compelling the full length of the ramp, at the Guggenheim through April 7.

Not all its voices are black. Farah Al Qasimi, say, is from Abu Dhabi, but for her, too, It’s Not Easy Being Seen. The curators, Ashley James with Faith Hunter, do not make plain just when race informs their choices. They seek only invisibility—as sought, imposed, a form of inquiry, or a matter of perception. Each has its own tier of the ramp, although the art keeps pointing to all four. Still, this could be the perfect survey of currents in African American art. It leaves out most fashionable figure painting and myth making, but such is the price of going dark.

To be sure, black Americans are seen more than enough, as stereotypes and objects of fear. Blackness itself can become visible, as a barrier or as an invitation to find comfort in the dark. Stacy Lynn Waddell and Tariku Shiferaw take that as their subject in the galleries, and so do the artists here. Invisible Man for Kerry James Marshall reduces to white teeth and white eyes—somewhere between a stage villain and a minstrel show. Faith Ringgold leans for hers on the flat, mute colors of African masks. The Invisible Man series for Ming Smith leaves its actors out on the streets, metal gates down for the night and covered with graffiti.

Still, Marshall is never less than amused, and Ringgold’s faces acquire warmth and individuality as both men and women. Smith’s photos build a larger portrait of Harlem, from children at play to adults finding sacred ground, but still at risk and alone. Sandra Mujinga’s Spectral Keepers are at once larger than life and forever hidden. Nine feet tall, they tower over the viewer in loose green pants and green hoods. They might almost be emitting a green light from within. And they are not the show’s last hoodies.

Kevin Beasley dips his sweats in resin as sculpture, while photos by John Edmonds lend his accents of sharp color, and David Hammons takes an entire bay for a single hood. With her hoods, prints by Carrie Mae Weems, are just Repeating the Obvious. Hiding behind clothes may take other forms as well, in Camouflage Waves for Mujinga and camouflage colors for Joiri Minaya. Doris Salcedo needs only needles and thread, while Rebecca Belmore needs only hair. Belmore’s shrouded figure kneels, in prayer or despair. It has straight black hair, not dreadlocks, but then the hair is synthetic.

Of course, the easiest way to hide behind a photograph or video is in the processing. A blue light hides Chris Ofili, leaving only swirls like loose curtains. Glenn Ligon prints each of his fifty self-portraits in a different off-kilter color. Yet Smith blurs her central figures with nothing more than her command of lighting, while prints by Stephanie Syjuco take on the rhythms of her shutter release. Sondra Perry speeds things up instead. A dancer’s uncanny blur contrasts with the stasis of an unfinished Sheetrock wall.

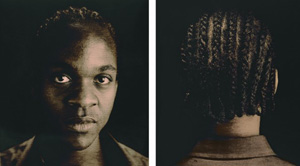

At the same time, they gain in presence. That, after all, is the show’s central demand. There is no escaping faces emerging from the darkness in close-up from Lorna Simpson, Ellen Gallagher, and Titus Kaphar. There is no escaping, too, the materials—Kaphar’s asphalt paper, Tiona Nekkia McClodden’s leather (as in kinky sex), WangShui’s oil on aluminum, or Tomashi Jackson’s marble dust on PVC, even when their images fade to black. Photos may also show only backs, paired with the sitter’s front for Lyle Ashton Harris. Your phone and the FBI may not ditch face recognition anytime soon, but these backs are personal and real.

Charles White enters as a kind of father figure, although his hard-edged portraits in a sea of swirls look decidedly old-fashioned. History itself takes a back seat, apart from dark landscapes by Dawoud Bey, including the site of John Brown’s tannery. One bit of history, though, could sum up the vital paradox of the show’s demands. The 1995 Million Man March cried out for dignity, even as an individual had to surrender to a million. Ligon depicts it in a diptych that leaves the other half black, and Hank Willis Thomas calls for One Million Second Chances in images of the nation’s flag and Capitol with all else fading into white. When Sable Elyse Smith counts the days and nights for prisoners, she could be counting out America for all.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.