5.7.25 — The Object in Question

Exactly one hundred years ago, a show opened in Mannheim with one eye on the future and a middle finger squarely in the public’s face. It was 1925, and Germany’s loss in World War I was not just a bitter memory. Soldiers came home to a shortage of affordable housing, the ruins of a wartime economy, and a new art.

It was time to make demands—on art and on society. It was time for a Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity. Now if only its dreams could survive the Great Depression and the Nazis—and if only the artists could agree on their objective. For now, they will just have to find what common ground they can at the Neue Galerie through May 26.

It was time to make demands—on art and on society. It was time for a Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity. Now if only its dreams could survive the Great Depression and the Nazis—and if only the artists could agree on their objective. For now, they will just have to find what common ground they can at the Neue Galerie through May 26.

Modern art in Germany had always had a confrontational spirit and a shortage of optimism, and the very idea of a New Objectivity may sound like a cruel joke. But then the movement made no excuses for starting over. This was no time for German Expressionism, with its implication of escaping reality. A smaller show, from the Kellen collection, has all that you might expect in wild colors and subjective impressions, through May 5, from Gustav Klimt and decorative portraits to /Wassily Kandinsky and Blue Rider. If a new movement, in contrast, came with contradictions, it also came with the promise of things as they are. Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub of Mannheim’s school of art had given it a name two years before, and even he thought it encompassed two directions that he could hardly reconcile.

Sachlichkeit in German can refer to the facticity of things or the facts, and Hartlaub distinguished “verists,” who faced a gritty industrial present, from “classicists,” who gave the future a more perfect union. If that were not enough, the Neue Galerie finds room for proletarian realism and Cologne progressives as well. It sees a meeting of art and technology, too, including the work of the Bauhaus, founded in 1919. The curator, Olaf Peters, includes Oskar Schlemmer’s painting of the Bauhaus that long graced the entrance to the Museum of Modern Art. It has Marcel Breuer chairs as well. If they are off limits to visitors, the future takes time to arrive.

It may arrive with a felt ambivalence as well. Marianne Brandt at the Bauhaus designed a clock, a telephone, a desk tray, an ashtray, and more. Nothing was beneath her. Models posed for ads for fancy jewelry, and nothing was above them. Still, a proper critique had to extend to consumerism. When an unemployed worker bares her shoulders to Otto Dix, the promise of sexual favors extends to neither one.

Reality here is treacherous, proletarian or not, but seeing it is half the battle. When photos by August Sander capture ordinary workers, they become individuals. Who needs Max Beckmann and his assault on Berlin nightlife when they can emerge into daylight? Other works focus on children, caring for dolls and one another. Others have the dignity of doctors, sowers, or educated readers. Still, it is a dangerous moment in a harsh world.

Exploiters may share the dangers with the working class. When capitalists meet for Georg Scholz or Franz M. Jansen, they cannot drop their pipes, their scowls, or their masks. When high society gathers around a felt table to make plans, most outright headless and mindless, the businessman looks like Donald J. Trump with a mustache, and a general sets down his bloody sword. A blind man’s dog looks bloodthirsty himself. Factories devoid of life for Carl Grossberg, though, look gorgeous. The future may be nearing after all.

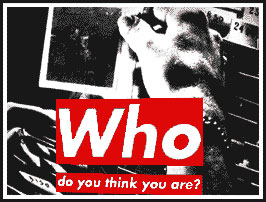

Art here all but denies the contradictions, and such as the price of a movement. It also leaves names that few will care to remember. Yet they make real demands, including the demand to face the alternatives. A row of portrait busts runs from youth and determination to near abstract sculpture to a robotic mask. A doctor shares a room of portraits with a madman, because who is not a madman or a patient? The convex mirror above the doctor’s head wants to know.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.