2.23.24 — The Fierce Urgency of Now

Elizabeth Schwaiger paints and paints again an interior teeming with art and, just maybe, life. To be sure, she hardly has room left for people. Paintings cover the walls and spill out into the entirety of the space, where they compete with sculpture. Furniture itself seems a mere luxury—or an additional work of art.

Still, she attests to the thoughts of a living artist—and the importance of art to her life. It has, as the show’s title has it, the urgency of “Now & Now & Now,” at Nicola Vassell through February 24— and I work this together with other recent reports on keeping painting busy as a longer review and my latest upload.

and I work this together with other recent reports on keeping painting busy as a longer review and my latest upload.

Martin Luther King, Jr., spoke of “the fierce urgency of now,” and Schwaiger knows its fierceness. She knows, too, that what is fierce is not always comforting. One can hear the repetition of her title pounding in her ear. If the title seems at all superfluous, everything for her is more than halfway out of control. Oversized sheets of paper spread out on the floor. They could be sketches toward painting, but they have pushed her finished work aside, and they appear as nearly blank sheets.

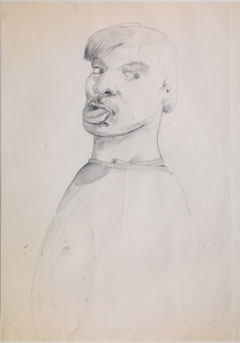

Their white stands out all the more because art has taken over in another way, too. Schwaiger overlays each painting with color, almost always a single color. She quotes “Diving into the Wreck,” the poem by Adrienne Rich, and the monochrome ripples and obscures like ocean deeps. You might well be underwater, and the artist is in way over her head. So is the sole human presence that I could make out with certainty, a gaunt white silhouette. It could be her or yet another work of art.

Art appears, too, as a living tradition, that of the artist in her studio and of layered color. Henri Matisse and “The Red Studio” epitomize both, but examples are easy enough to find. The Met sets aside a large room for the genre in its new galleries for European art. (It displays Kerry James Marshall, the contemporary black artist, and Schwaiger, still in her thirties, has her show a black-owned gallery, although she is white.) It can serve as a statement of identity or a celebration of art, and she may use a second color for highlights on sculpture. She has also used the studio, in an earlier painting, as a meeting place for many more.

Diving into the wreck sounds grim, but it has its attractions. Think of the appeal for divers of the Titanic. She also proclaims her love of childbirth and scuba diving, as inspirations for her art. Both recall her joys, her pain, and her fears. Mostly, though, she misses the fierce urgency. Like Rich, “she came for the wreck and not the story of the wreck.” It is the age-old appeal, again quoting Rich, of “the thing itself.” It sounds ever so Romantic (or Kantian), but it survives in late Modernism’s plea for “art as object.”

It also sounds ever so important, and Schwaiger also quotes Rainer Maria Rilke, the Austrian poet, in case you missed the point. She is not, though, pedantic. She really is painting art as the thing itself, to the point that its subjects within her paintings are left unseen. She may speak of the wreck of her art and perhaps her life, but her studio looks great. It has the ornate mirrors and transom windows of a European palace or museum. For all her preliminary smaller paintings, she needs the overflow of art and color.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.