9.19.25 — Behind Nature

Artists have long delighted in flowers. It puts to the test their powers of observation and commitment to nature. It brings out the possibilities in media such as watercolor, with its fluid line and still more fluid color.

All well and good, but Hilma af Klint wanted more. She asked “what stands behind the flowers.” A show of that name asks with her, at MoMA through September 27, and it reinforces the case for af Klint as a progenitor of abstraction. Ah, but then what lies behind that? If your answer is nature, she would not mind a seemingly vicious circle. She felt pure form as essential to both.

All well and good, but Hilma af Klint wanted more. She asked “what stands behind the flowers.” A show of that name asks with her, at MoMA through September 27, and it reinforces the case for af Klint as a progenitor of abstraction. Ah, but then what lies behind that? If your answer is nature, she would not mind a seemingly vicious circle. She felt pure form as essential to both.

Hilma af Klint was on hardly anyone’s radar when the Guggenheim served up a 2019 retrospective, but then neither was abstract art when she began to make it. She had a reputation, to the extent that she had a reputation, as a Symbolist, and that could upend the history of abstraction. Her first nature studies at MoMA date to 1908, when itself was barely in flower, and the Swedish artist may not yet have heard of it. Born in 1862, she came late to the job, but she had an interest in flowers even as a student, in essays and notebooks. It took a direction not even she could have expected.

She kept her studies of nature and design separate at first, but barely. Her first dated studies could be symbols in an unknown code. Curves break away from larger circles, condensing into bulbs, buds, or seemingly nothing at all. Undated studies keep their eye on the ground and the forest canopy, with ferns and soil running densely the width of the paper. You are likely to remember them for their texture without quite known whether that derives from botany or art. Subsequent studies, starting in 1918, focus on the radiance of circles and squares without a flower in sight.

Still, af Klint’s drawings have a single impetus, and within a year or two they came together at last. A flower study follows the vertical course of a branch or stem. So, to its side, do small colored circles, like stills from a cinematic color wheel. More often, she pairs flowers with an actual color wheel or rectangle, with diagonals that need never meet. Are they the components of art for art’s sake—like color wheels or nested squares in the days or Josef and Anni Albers—or even today? Do not be too sure.

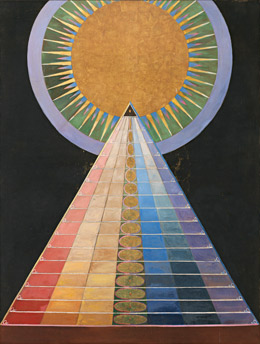

In those same years, she was pursuing comparable shapes in painting, as suns, pyramids, and altarpieces. They make a point of their radiance, but are they bringing a heavenly vision down to earth? Without the obligation to compose a major painting, the madness is all the greater in drawing. She has a parallel, too, in the painstaking course from nature to abstract art in Wassily Kandinsky. Yet she is less inclined to leave flowers behind, not even when, with her Atom drawings, the lure of science shifts from botany to quantum mechanics. She worked in series and soon had her largest, Nature Studies, and she spoke of all her work as a botanical atlas.

Notice, though, how nature keeps its distance, behind the curtain behind the curtain. Some studies allow words back in, as in her student essays, but perched on spirals. In the show’s last series, radiance becomes the aftereffect of an explosion. Here she unleashes the fluid nature of watercolor, with shades of blue, yellow, and especially red changing its shade as it covers a sheet. Notice, too, though, the humility, even banality, of her approach to nature, much as in her early ferns and fallen leaves. If a fly or an ant enters the scene, it counts as both nature and art, too.

She may seem to have outstayed nature’s welcome, as modern art was coming to be. The popularity of nature studies reflects the ideals of Romanticism, from John Constable to Beatrix Potter, in observation and expression. It comes with a moral, too, ever since flowers in Flemish still life became a parable of decay and death. Still, af Klint refused all that quite as much as Modernism. Swedish winters hang on way too long for her to abandon the first signs of blossoming. What lay behind the curtain was the impress of the curtain itself.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.