5.1.24 — One Last Step

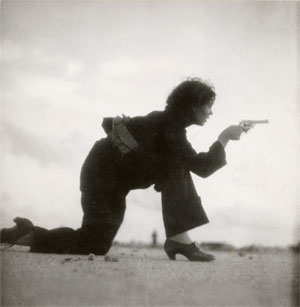

Henri Cartier-Bresson helped to found Magnum, the authority when it comes to photojournalism, but he also defined art photography for generations as the “decisive moment.” Can the International Center of Photography take one last step, from representation to abstraction?

Not exactly, but change comes from an unlikely source. Robert Rauschenberg, rarely a photographer and hardly a formalist, turns a stairwell into a study in black and white. The steps themselves approach Modernism’s grid. When I reviewed “ICP at 50” in March, I promised to return to the story of how public and private were hard to separate all along, like photography and art. May I do so now? (With apologies for such old news, you will see why I chose today when I come to a second show.)

You might think again of those steps when you come to the stone tiers of a college amphitheater, from Imogen Cunningham, and again on opening day at Ebbets Field, in a photo by Charles E. Stacy. From breaking events to abstraction and back, photography has come full circle. ICP is not so much broadening its mission as reinterpreting it each and every day. Sure, this is street photography, but the streets of New York now belong to the loser at a diaper derby by Diane Arbus. And sure, Weegee joins in her freak show, but on the set of Dr. Strangelove.

The show does only what you expect, only not necessarily when you expect it. Photography can still keep up with the news, like Bill Biggart on 9/11, but his car coming at you out of a cloud of dust seems to belong less to tragedy than to a vision. It can still make news as well, as childishly and notoriously as Piss Christ by Andres Serrano. It can still write home, but the letter may go from Samuel Fosso to his ancestors in Africa. Dining on the Congressional Limited, by Robert Frank, hangs next to diners in Brussels with their dog, by Eliot Erwitt. Who can say which deserves the headlines?

An exhibition is not a text book. Can a selection, anywhere, lay claim to a comprehensive history of photography—and what can it claim if not? This is not the institution to play around, and what is art without room for play? The nice thing about an anniversary is that you do not have to ask. Shirin Neshat may sum it all up in a single image, of Persian writing across a downturned face. Public and private ends of photography can be equally moving and equally inscrutable.

An exhibition is not a text book. Can a selection, anywhere, lay claim to a comprehensive history of photography—and what can it claim if not? This is not the institution to play around, and what is art without room for play? The nice thing about an anniversary is that you do not have to ask. Shirin Neshat may sum it all up in a single image, of Persian writing across a downturned face. Public and private ends of photography can be equally moving and equally inscrutable.

ICP may shy away from abstraction, but the Morgan Library cannot get enough of it. It appears often among recent acquisitions in photography, through May 26. All came to the Morgan since it established a photography department in 2012. Just as interesting as the images (or refusal of images) is the variety of means used to create them. Than can mean brushed chemicals for Chargesheimer (a German photography), a distorting lens for Weegee, cut-and-past fragments of photography for Joe Rudko, books stacked like white paper bricks for Mary Ellen Bartley, or a mere close-up for Carl Van Vechten. Irving Penn can turn most anything, from a whirl of fashion to food, into form alone.

The Morgan finds art itself glamorous, because it, too, is a class act. It has a whole wall for photos of celebrities in the arts, and they play their parts well. Add in a group shot of a supportive dealer and her roster of artists, by Peter Hujar, and you can almost forget Hujar’s vulnerability and honesty in the face of AIDS. Eleanor Antin mailed out dozens of her photos as postcards, and the Morgan managed to get a complete set back. She had crossed the country, ending at the Museum of Modern Art, and this was her message to the country in return. It may lose something on going from conceptual art to a monument, but one can always end instead at ICP and start your own journey anew.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.