Underground Comics

John Haberin New York City

"As to poetry, you know," said Humpty Dumpty, stretching out one of his great hands, "I can repeat poetry as well as other folks, if it comes to that —"

"Oh, it needn't come to that!" Alice hastily said . . . ."

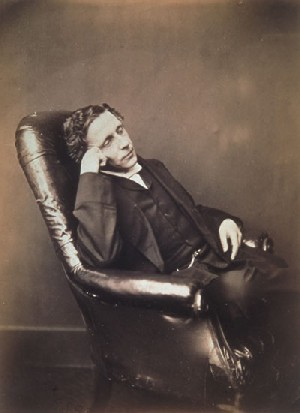

Dreaming in Pictures: The Photography of Lewis Carroll

I knew Postmodernism that had peaked when Lewis Carroll came under fire. If modernists were not bad enough, even Alice's favorite grownup had become a dead white male. In nude photographs of children, he left the hard evidence in plain sight. Advocates of recovered memory syndrome could only envy art historians for their moral clarity.

Now, a large exhibition leaves the emperor of Wonderland with too many clothes.  The nudity is gone, for both children and grownups, but their vulnerability remains. Has Carroll pierced the veil of Victorian manners, down to the naked truth, or has he found only another pose and another dream? The paradox makes Carroll more vivid and relevant than ever. In turn, to see him plainly, it helps to see the shifting rediscoveries of his work for decades now.

The nudity is gone, for both children and grownups, but their vulnerability remains. Has Carroll pierced the veil of Victorian manners, down to the naked truth, or has he found only another pose and another dream? The paradox makes Carroll more vivid and relevant than ever. In turn, to see him plainly, it helps to see the shifting rediscoveries of his work for decades now.

Theaters of the mind

I always liked Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, but I, too, have had to rediscover him. The Annotated Alice hit me at just the right moment, early in college, where I studied physics. With his ingenious annotations, Martin Gardner produces more than a picaresque storyteller. Behind the weird, new characters in every chapter, the Oxford don laid his plots as rigorously as a chess game. With all his nonsense rhymes, the clergyman satirized English poetry and morals. In Alice's adventures and riddles, the old mathematician pushed logic to its perilous limits.

I saw a playful, somewhat repressed outsider with a mathematical mind, a passion for real literature, a sympathy for childhood loneliness, and an urbane, unflinching eye on the adult world. In other words, like any overgrown teenager in love with books, I found a tidy version of myself. Yet it took effort to see him as a photographer, too. John Tenniel was the true artist, right? Who cares what Alice Liddell really looked like? And you mean she had sisters, too?

Perhaps it took effort for Carroll as well. Out of thousands of prints, he published little more than a hundred.

It took too much effort for Modernism for sure. Compared to the formal perfection and documentary vistas of later photography, Carroll's amateur theatrics may look quaintly Victorian—not unlike a parallel in America in Alice Austen. Compared to Surrealism, they may appear more like Freudian symptoms than an analysis. Even compared to Carroll's stories, the photos seem to have it all backward. Staging appears casual, almost artless, while the sexual undercurrents come so obviously to the surface. Small children posture, while their parents carry on in what passes for naturally.

Carroll did become a modern in the end, but the hard way, starting with a harsh backlash. The theater now earned an R rating. Those nude photographs—yes, all four of them—sure look suspicious. From the first daguerreotypes, photography had served as erotica. The male gaze, feminists have argued, dominates art up through Modernism. With Carroll, a man who never married turns his gaze on childhood. People who grew up on Alice still shy away from him as sexist or creepy.

However, also as part of the postmodern critique, artists are helping to recover Carroll for today. Painters and photographers have returned to Surrealism and its objects of desire, but without its aura of impulsive naturalism. They have taken sex and sensation alike as theater, and Carroll suddenly fits right in. Two summers ago, he and another English photographer, Juliet Margaret Cameron, anchored a show called "Visions of Childhood," right up there with artists of today.

From the past into history

Yet Carroll's adventures in art land have at least one more chapter. At last comes acceptance, without irony, all in its proper place and time. Art history has, almost, the last word. Back then, one learns, all artists play to the audience, and photographers stage events rather than neutrally record them. Those days make even modern photography look like naive realism. Besides, some critics hasten to add, pederasty requires children, and childhood amounts to a modern invention.

In retrospect, Carroll simply acts out the stages by which art becomes an institution. First comes rejection as something safely past. Next comes rejection as something inconveniently present. Then comes appropriation as something contemporary. At last comes cold historical fact, a place in the canon.

Carroll treats children and adult actors pretty much the same, with due respect for English convention—or does he? Carroll has still not emerged from the rabbit hole.

Sure, these kids dress for the occasion. They stand by their parents in their Sunday best, but they fit uneasily into their clothes. They take to an imaginary stage, costumed as figures out of all the right myths, but the villains cannot be bothered to attend. They assume the patience of an obedient child, but their impatience shows in their eyes. They enact the wise virgin at least nearing rescue, but the rescuer, too, is only a child pretending.

Within moments, a single photo can look eminently Victorian, precociously modern, or simply like children. In the end, Carroll's peculiar appeal may lie in the changes. Like a child himself, he sees how much it takes to carry on like an adult. Like a bit of a modernist after all, he sees how much deception lies in plain sight.

"All on a summer afternoon," Alice's adventures begin. In one summer afternoon now, one can have enough versions of Lewis Carroll to confuse Alice herself.

No nudes please

The International Center of Photography has room for all these, but it leans toward the period piece. Historicism, with artists along a time line, suits the Center's move from its Fifth Avenue brownstone to a midtown corporate lobby. The new ICP space makes pretty much any work look institutional—and more than a little lost.

Carroll gets the main floor, and no nudes please. Laid out without regard to chronology, the show seems to present a single pageant. Cast members come and go, including such real-life adult actors as Ellen Terry and her sisters. Adults appear as well in those family portraits and in a self-portrait. The children, in fact, seem the least exposed, behind layer upon layer of costumes and poses.

Carroll gets the main floor, and no nudes please. Laid out without regard to chronology, the show seems to present a single pageant. Cast members come and go, including such real-life adult actors as Ellen Terry and her sisters. Adults appear as well in those family portraits and in a self-portrait. The children, in fact, seem the least exposed, behind layer upon layer of costumes and poses.

Downstairs, a small, darker room focuses on nineteenth-century literary images. Facing Cameron, to name just one, famous authors glower. Their stories do not so much come to life as stand terribly still. A black cloth guards some photographs from fading with exposure to light. It makes them seem that much more remote, as if frame, glass, and curtain had become an art object of their own. Deciphering the drama, I want to say, would bring me closer to an ancient mystery—or a postmodern installation.

Carroll, no doubt, would blend in just fine downstairs. He, too, strips the pageantry of late Romantic painting to its essentials. Out go the orientalism and prurience of Victorian nudes. Out go the exotic stage sets or even discernible interiors. One remembers faces, half dwarfed by home-made props and household furniture. One remembers moral fables duly rooted in English history and literature—the knight rescuing the maiden, the Shakespearean heroine still hoping to fend for herself.

Every medium begins with a technology and a borrowed heritage long before it has its own message. Video art still looks to television and video games, painting and sculpture, installation and performance, computers and the movies, and even opera. Early photographs, historians insist, copy paintings more than nature.

At the ICP, one sees even more photography's roots in words. Cameron photographed Alfred, Lord Tennyson, who helped to make King Arthur so central to England's vision of itself. Ellen Terry found her most obsessive groupie in another writer and public performer. Charles Dickens tormented himself for years over her, while grinding out his darkest and finest work.

Pretending to pretend

Carroll and Julia Margaret Cameron both lay on the costumes and stage lighting. Both elevate the individual, but as part of a morality play. In both, kids play dress-up or dress-down. Both shut their eyes, click the shutter, and think of England. Besides, as a mathematician, Lewis Carroll would have enjoyed calculating the six permutations of Cameron's three first names.

So why does Carroll look contemporary again? What makes her scenes so stagy today? And what makes his own so moving?

For one thing, he refuses to go over the top. He would never have let Tennyson arch his brows or outlined them in shadow. He never forgets that his cast is just pretending, and they and the viewer know it, too. In these ways, too, he creates a bond of understanding between the child and the photographer, and he lets the viewer in on the secret. Children really do play games, and so do grownups, and Carroll empathizes with how much they have at stake when they play.

Think back to Alice's adventures underground. Alice encounters adults as if forced to join a game in progress. She has still to learn its rules, and the rules have a logic far too firm ever to make sense. They echo the sermons of familiar adults, but with the tidy moral twisted beyond recognition.

Children, in turn, are always playing at games and at putting themselves into adulthood. However, that makes childhood a pretend game of pretend, and the possibilities get out of hand all too easily. Adult games start to look scary, confusing, and funny. On top of that, childhood now demands innocence, but so does Alice's incomprehension. Childhood may give way at any moment to sexuality, but the signs lurk there all along, making the confusion worse. Childhood can leave one naked, and adulthood can require a costume.

Carroll's children do not simply go along with the drama. They do not get to play the rambunctious, wiser types among dumb grownups either, like so often in children's books now. They risk a man's ogling, but they neither welcome his gaze nor perform blissfully for his benefit. They do not so much stare back as stare off to one side. No wonder they seem put upon, brave, or just lost.

Great expectations

My Victorian history has things much too pat. Yes, photography began as literature, art, and theater, but all of these had close claims on reality. Technically, after all, photography had its roots in the camera obscura, which painters, too, used to discovery individual perception. The exhibition title, "Dreaming in Pictures," sounds nice for Alice. Yet in its overtones of escape, it overlooks how hard Carroll works at disturbing everyday reality.

Yes, childhood took an invention, but it came into being only slowly. Think of Dickens again and Great Expectations. Estella, thanks to her class status, gets an extended childhood of study abroad. Pip must settle at first for apprenticeship into an adult trade, and a girl of his class would have married young indeed.

Conversely, childhood came with a new ideal of innocence, but the same ideal carried over to womanhood. One in need of nubile young women could revisit Salon painting and the Victorian nude. In other words, the old ideals were falling apart, and the new ones were heading for a collision. Carroll welcomes that. While mostly his boys and girls play parts appropriate to their sex, a few girls play the hero. It serves less as a direct attack on gender roles than a subtle reminder that, like Alice, even a girl as a girl can maintain her courage.

Carroll, as Cameron never could, takes part in the transition toward new ideals and a new art. Victorian theater plays out in front of an audience, leaving them moral choices. Starting with Carroll, theater plays out in awareness of its audience and all the paradoxes that brings. A new generation of painters, such as Edouard Manet and Edgar Degas, felt the same way. Fittingly, the room downstairs includes a photograph modern art's first theoretician, Charles Baudelaire.

The modernist critique had it right after all. In family portraits the adult really does look composed, while the child looks half angry or bored. The stories really do fail to close, with roots in the picaresque and the possibility of an open ending. Carroll belongs to a lot of eras, because he helped to define them. Even children can have great expectations.

Another show could do more to rescue Carroll from historicism by giving him more of his own history. I would like to see the works in order. I would like to see a separate room for the prints he made himself. The ICP, like most accounts, relies heavily on modern prints from Carroll's negatives. Still, it leaves one with a child of his time stepping into another as if into a dream.

Mostly, Carroll's subjects keep their costumes and their clothes, but they get to be real people, despite the theater. I think often of one of Carroll's repeated themes. A child—Xie (for Alexandra) in one photograph, Juliet Arnold in another, Alice's sister Edith in a third—reclines on a sofa or unmade bed way too big for her. Is she posing or drowning? She is childish, funny, beautiful, even sexy, and maybe, must maybe, ready for an adult willing to understand.

"Dreaming in Pictures: The Photography of Lewis Carroll" ran through September 7, 2003, at the International Center of Photography. Related reviews look more fully at Julia Margaret Cameron and at Cameron and Lewis Carroll together, in "Visions of Childhood."