Go Fish

John Haberin New York City

Bill Viola at the Whitney

Can one look a fish in the eye, and what would one see? For most people, warm-blooded animals have the wide eyes and precious smile of a child. In cartoons and fables, they display the warmth and vulnerability, the trickery and genius, of adults. Fish look familiar, too, but also repellant. Meeting their eyes feels like a dead-fish handshake.

One faces a surprisingly similar lens at the Whitney Museum—the video camera of Bill Viola. With a technique rarely matched in art today, not even outside video, Viola searches nature in hope of finding his humanity. What he finds instead are cold comfort and a cartoon of childhood. An earlier review describes my first encounter with Viola's operatic journeys, and a later article reviews his use and abuse of art history. A postscript here brings the saga up-to-date for late 2005.

Seeing eye to eye

In the open-air markets of Chinatown, just blocks from Soho galleries, the freshest of the day's catch looks painfully exposed and yet remote. A digital Chinatown for Cao Fei has nothing on the real one. Magic realism has nothing on this one.

Stephen J. Gould, the science writer, points it out: people judge consciousness by analogy to their own. As he says, a fish eye is "homologous" to a human's. It fell, that is, from the same evolutionary tree. And yet many vegetarians, he notes, eat fish. I can see why, so far at least, Damien Hirst and his version of "shock art" sticks to cows.

Hauling out paleontology to measure intelligence may sound kind of fishy, but Gould has a provocative point. The eyes have it. A fish-eye lens, in fact, expands the human eye and deepens its vision.

In the eyes of others, as in a mirror, people seek recognition. I should know. Anyone as shy as I am turns others off sometimes by not looking them in the eye. Conversely, in New York looking strangers in the eye comes with risks. A gallery-goer understands another risk, too, for the eye deceives.

Bill Viola's retrospective in New York take those risks. His video camera tries to piece out what makes anyone human, and he goes about it by shoving a stranger's image right in one's face. He takes literally an old metaphor for artistic genius—a lens on the world comparable to a human eye.

If Viola is right, the fishy experience might take one closer not just to nature, but to one's own humanity. Unfortunately, the eye of nature may hold some dirty secrets about art's humanity.

Humanity in the eye of nature

Bill Viola makes illusions but does not believe in them. He depends on a lens, the lens of his video camera, but he wants to startle the viewer out of illusion. He wants to bring art back to a more primal humanity.

Entering Viola's retrospective, I was overwhelmed by his control of video as a medium. (How could he possibly be left out of "Signals" at MoMA?) But shock after shock dissolves the illusion, and that is his point. I cannot stare at the world as in a comfortable theater seat. At some point, I have to enter into the enactment, let it stare me back, and find myself in my own choices.

Other video artists know their medium—on either side of the screen. They may even forget to get past the gadgets. A whole show of video's "Mediascape" at the Guggenheim clung to the hardware and software for meaning. Then, too, a pioneering video artist like Gary Hill, Joan Jonas, Anita Thatcher, or Bruce Nauman, or even a younger one like Erzstbet Baerveldt, can get past the illusion and the video games. They can make an ordinary, literal image—a human hand, a tortured face—hard to understand.

Viola takes another tactic. He does not really care for illusions, and he does not believe anything can be literal. He wants instead to question the medium's belief in the viewer's eye. He repeats that idea in his preliminary notes, on display in a quieter room off to the side.

As one sketch puts it, what is missing from video art is the viewer. For Viola, that means something is also missing from the viewer. The artist and viewer may think they can rely on their inner eye. Ordinary myths revel in the eye of the artistic genius, the eye of human consciousness itself. Consciousness has to learn its dependence on the eye of another, the eye of nature.

The eye of nature suggests, too, another side to Viola's skepticism. Nature defines him because it fills him with awe. As in last year's museum show of just two works, Viola spends his life in slow motion, like lovers in a TV commercial. Too often, nature turns into an excuse or a platitude.

Illusions of grandeur

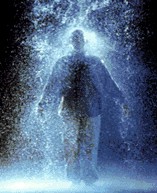

In Viola's best work, nature's eyes confront each other with a jolt. Take a striking one that also appeared in last year's show. On one screen a man strides forward, again in slow motion, until he is larger than life. The slow stride, arms held wide, announces a clichéd masculinity. The stance also toys with "frontality," the modernist dogma about a painting's presence on the wall. As a less-than-macho viewer, I knew I was in for it.

At least I thought I did. On one side of the screen, flames rise at his feet. On the other side, water is dripping lightly on his head. The fire and water grow in intensity until they consume the man and die. Since the man is Viola, something of the artist's superiority to his art has died with them. Although I found the illusion impossible to catch even over four viewings, I knew all too well to look for it. Could it top the experience years later in person of walking through water outside MoMA?

Not every work is so extravagant, but the crash landings start in the very first room. Four screens there hold titanic images of nature. They could be midway on a time line from the Romantic landscape to Sony Imax surround theater. And then the images fly to bits with a piercing sound, only to reassemble. I had to take a stand and choose a screen. Yet I also had to stop anticipating and let the crashes come.

Most works force the viewer to repeat that pattern—of looking, recognizing oneself, and dissolving. A camera projects a single drop of water as it builds, but the projection captures the viewer's image in the drop. Then the drop falls and bursts, but not before landing on a heavily amplified drum.

In another room, a pair of women meet in slow motion, while another woman enters the scene. Are they intimate or afraid? I could only wonder at their actions—and my own.

The street scene, the three women, and the startling colors of their clothing come right out of a Mannerist painting. As in a Visitation, a story of the Virgin coming to know the birth within her, these women stake so much on mutual recognition. Yet their act of recognition has slowed down so far that it may never take place.

The new age on Imax

Not all in Viola's art is so knowing or innocent. Think about it: art as a last hope of recognition, fire and water, youth and age, eternity in a drop of water, hidden presences beneath the reality one can see. It literalizes new media as a flood of light. debunking of humanity has an awfully new-age sound, and his new-age ideas get simplistic all too fast.

When Gary Hill makes a gallery visitor step over video cables, the viewer is indeed part of the work. When Hill makes one face a row of homeless men, one is oneself shorn of a home. In contrast, I never did see myself in Viola's drop of water.

Philosophers have dismantled Descartes model of the mind as an inner theater. Outside of art and philosophy, too, consciousness has taken a beating—from political terror and ordinary neuroses. Like philosophers and psychologists, Viola thinks of a viewer actively making choices, rather than just enjoying a movie. His problem is that his rhetoric is right out of the old male action movies, like Matthew Barney and Barney drawings today.

I admired the show, but somehow I tired of the same trick again and again. As with Chuck Close, another artist with a magician's hand, I became suspicious of the control freak who created the maze of rooms. I had doubts about that supposed humility with respect to the viewer, when art was assaulting me with random shocks. I knew, too, that Viola had lost Close's cutting edge of disbelief.

Critics have complained about Viola's installation. They dislike how sounds and images leak from one room to the next. Viola may like that leakage. It makes the random shocks more random.

To me, however, it also means I am being set up. A retrospective on this grand scale ends up deadening the shocks. One can finally see through the illusions.

The hands of the sushi master

Viola brilliantly recreates the experience of looking, experiencing, and making new choices. But did I ever really have a choice?

Viola might as well be playing three Wagnerian operas at top volume, simultaneously, and pretending one can decide which plot to follow. Like plenty of younger artists absorbed in theatrical metaphors for art, he might as well be designing theater sets and complaining that the actors have not yet begun the play. He is a carnival trickster after all, and his use of scale reminds me of Sony's commercialism, too.

I enjoyed this work, the way one appreciates the hands of a sushi master. I loved the quick moves. I understood a new idea of the mind, one inseparable from physical skill and bodily limitations.

I saw a new idea of genius, one that means stepping outside one's head—and using one's hands. I looked into the mirror behind the sushi master, and I had to see myself more strangely.

Like many modern artists, Viola takes Gould's assumptions apart bit by bit. He makes it harder to spot one's own image in art, that supreme human creation, much less in an animal or a fish.

He still likes the discomfort of the fish eye, however, a little too much. He insists on it, in fact, until it stops bothering me. I am heading out for sushi.

A postscript: from fish eye to car wash

I had a transcendent moment one Friday night seven years later, all thanks to Bill Viola. It did not come as he strode through fire or as a naked couple held their furious, protracted kiss entirely underwater. It did not come with a broad-spreading tree, its bare branches drenched first in light and then in darkness, only to reemerge with the dawn—all in slower than slow motion. It was not as another bare-breasted woman, like an X-rated Lady Macbeth, perpetually washed her hands on split screens.

Rather, it came after, as I turned and began to walk home. The door of a car wash stood open to Tenth Avenue, and still more water tumbled down, along with plenty of suds. Viola's epiphany of light had finally entered the twenty-first century. I imagined it on video, first from a great distant, as a tiny rectangle in the darkness, only to grow and finally to surge past me, perhaps to run me over in the process. I would have understood mortality, not to mention insurance and resale value.

Viola's existential mysteries keep making me laugh, except when they make me angry or bored silly. However, a 2005 gallery exhibition should leave no doubt of his technical and visual mastery. I can laugh all I want, but he draws crowds for a reason.

Sure, one has to accept life as a passage through fire or a sacrament best shared with thousands on a wide screen. One has to accept drowning as an ecstasy akin to love and love as a commitment never to smile. One has to accept that one has seen his operatic visions of fire and water, masculinity and dread, many times before. One has to accept that they become more awash in the superficial trappings of high art each time. Still, if one wants to know how he does it, this exhibition focuses more than usual on the illusion.

Instead of a loose quote from the Pontormo, he begins with a tree on a hill or a break in the darkness. One could mistake the latter for a small, tubular bulb, as in an old analog device, and in fact his approach hinges on using new media to evoke an age before the digital. The light grows into a man, Viola himself, who indeed does stride through fire, giving off a shower of sparks. Then a taper lights to a single copper lamp, and the camera draws back smoothly to reveal shelf after shelf of lamps. One hardly notices the transition as they increasingly leave the woman who sets them aflame in silhouette.

Viola is developing some of these images in conjunction with his plans for the design of a Ring cycle in 2006. (Could this be what turned Nietzsche contra Wagner?) I may wish that he earned his intimations of mortality without the pretence, like Rebecca Horn, say, as when he simply held his breath in an early video. I may wish that he visited this planet more often, as with the tree—or maybe even a car wash. I may wish that he explored new media rather than bathed one in them. However, if you find that Lord of the Rings just does not look the same at home on DVD, at least you know where to go.

Bill Viola's show ran through May 10, 1998, at The Whitney Museum of American Art. His 2005 exhibition ran at James Cohan through December 22. I have placed it here because it fit with the issues raised by his retrospective, but also because I already have three searchable reviews of Viola—this one, my initial encounter in 1997, and reflections on his slow-motion dramatizations of Renaissance painting.