Mannerism as the Renaissance

John Haberin New York City

Jan Gossart

If you remember your art history (or have read too many of my reviews), you know that Mannerism came at the tail end of the Renaissance. No sooner had the High Renaissance defined a norm for art and its highest achievement, Mannerism deflated it—and the air kept spewing out in all directions for nearly one hundred years.

Where the High Renaissance put a city, Rome, at the center of the map, Mannerism covered Europe. It could invoke anxiety or a chilling lack of feeling, extravagant displays of skill or deliberate distortions of space and form. It could copy or subvert existing art, but it kept reflecting on what had happened. Art itself now had detractors from theorists of art—the very ones who coined the term Manierà.

If all that sounds akin to the success, drift, and tensions in art today, it should. Many uncomfortable with harsh implications of "mannerism" prefer to speak of the late Renaissance. I like to call it the Post-Renaissance or even Re-Renaissance, like a Postmodernism for classicists.

At least one standard version of history runs that way. But what if history ran backward? Jan Gossart supplies just such an alternative. A virtuoso schooled in Mannerism, he quickly turned for lessons to the early and High Renaissance. Yet by bringing together the chief currents of northern European painting, he set a standard of his own. It is a chilly or discomforting standard, but it earns him a terrific retrospective.

Mannerism as classicism

Of course, history never runs in straight lines. Gossart (often spelled Gossaert) certainly did not. He fit in easily, but he never quite settled anywhere. Maybe it speaks to his rootlessness that he often incorporated a version of his small hometown, today's Maubeuge, into his signature or monogram. He worked for princes, but he could at least claim something plainer and his own as a point of origin. You may have heard of him as Jan Mabuse.

Born in 1478, he gravitated to Antwerp, where a school of Mannerist painting was already underway. He took quickly to its fine line, acid colors, and compositions crowded to the point of chaos. In early drawings, elaborate architecture dwarfs the tiny figures set into its niches. Stairs lead away from Saint Catherine and into nowhere, and that attention to skill, intricacy, and imagination stayed with him. In a Madonna in oil from his early thirties, Mary's ornately gilded throne towers unpredictably over her head. When he collaborated with others, he always painted the drapery.

Already, though, Gossart wants something more—something clearer, firmer, and more natural. In perhaps his first surviving painting, the Holy Family takes a graceful, unhurried pace. Mary and Joseph move together at the composition's center, combining greater weight and human warmth. Mannerism's colors have softened, and its billowing curves translate into fuller bodies and fluid motion. Elsewhere an implausible background includes buildings, angels, a distant landscape, and a fountain in between, but each layer of depth gets ample room. One can forgive the infant Jesus's royal pose, given that he leans on Mary's breast for support.

Still in his twenties, the painter heads for Italy, where four years exposed him to the Renaissance and the Classicism that inspired it. His sketches stick to sculpture, both ancient and modern, and they provide him with motifs for painting and the Renaissance etching. He looks to them for solidity and form, rather than compositions and ideas. He also naturalizes what he sees, as if he were drawing all along from life. A boy removing a thorn from his foot copies sculpture, but you would never know it. Faces look up, where the original looks down, to insist on mass and mass alone.

Back home in the north, he tries to combine what he has learned, but not without fresh experiments and fresh tensions. The lion accompanying Saint Jerome has a human face—and a grisaille, or painting in shades of gray, has the drama of a night scene. Foreshortening flattens the Jerome's body and face of Jesus on the cross. Still, Gossart does not stumble for long, and he is gaining both students and attention. He enters the employ of Philip of Burgundy in Utrecht and Brussels, and it gives him perhaps his single lasting point of stability.

It also brings him new connections and still greater immersion in the Renaissance. Philip, a bastard child in a noble house, had influence and patronized the arts. He commissioned work from Gerard David and Simon Bening in the north, and he brought another painter, Jacopo Barbari, all the way from Venice. Gossart collaborated on paintings with David, who added the round faces, and Bening, who took care of the landscape. They also represented a link back to the very first generation of the Northern Renaissance, in Jan van Eyck and, after him, Petrus Christus. Between Jan van Eyck, Italy, and Mannerism, Gossart was finding a style.

Mannerism as art

van Eyck and the High Renaissance may seem worlds apart—or at least half a continent and half a century apart. However, Gossart might well have been searching for them all along. He must have fallen in love with van Eyck's combination of Gothic architecture and a luminous present, even as he bridged the two through sensual form rather than light. Petrus Christus, van Eyck's finest pupil, had already added a greater simplicity and humanity. Now David brought those lessons home. He and Bening both made close copies of van Eyck's Madonna in a Cathedral, as did Gossart, who also made its vision the setting for his Saint Luke Painting the Virgin.

It was as otherworldly a vision as Gossart would ever accept. His shadows and colors were already becoming heavier and earthier, and so were his subjects. He toys with myth and worldly sophistication, as in a painting of the god who lent his name to the word hermaphrodite. He paints Adam and Eve not separated by temptation, but sharing a panel lovingly, across from the tree of knowledge. He puts Mary and the infant Jesus through any number of roles, from human mother and child to objects of desire. One can see why the curator, Maryan W. Ainsworth, calls the show "Man, Myth, and Sensual Pleasures."

In short, he is adapting the past to Mannerism after all. He even pores over Albrecht Dürer, the north's most committed classicist, while adjusting him to the new model. In a copy after Dürer's print of Adam and Eve, Adam takes on a heavier complexion and a full beard. The tiniest of adjustments to Adam's contours bring his feet closer to the ground, his chest closer to less heroic proportions, and his arm closer to Eve. The Met's forced choices end up emphasizing Gossart's worldliness as well. Although it has managed to obtain fifty of fewer than seventy surviving paintings, the omissions lean to religious scenes, and the show fills out the retrospective with copies, students, and influences.

The artist has little interest in dogma anyway, not even in Europe entering the Reformation. He obtains such close access to van Eyck's Ghent Altarpiece that he does not just copy it, but begins by tracing it. And then he removes the pope's mitre from Jesus. Yet he has even less patience with Protestant assaults on art's "graven images." His Saint Luke Painting the Virgin is first and foremost a plea for painting—with Luke dignified by Moses above and by shedding his sandals below. Art itself lays down the law and stands on holy ground.

Art as commentary on art is altogether Mannerist, and Gossart cherishes it even when he plays the Renaissance master. When he gives his figures greater sculptural form, he is also treating them as sculpture. Their skin may become pale as stone, and Jesus in his torments sits on a cold stone as if on a pedestal. In part, the artist has equal access to van Eyck and the High Renaissance because he can treat both as mere styles. One painting in the tradition of the Netherlandish diptych sets its figures in Gothic niches on one side and Renaissance niches on the other, while others supply a painted frame. This is Mannerism as art of the usable past.

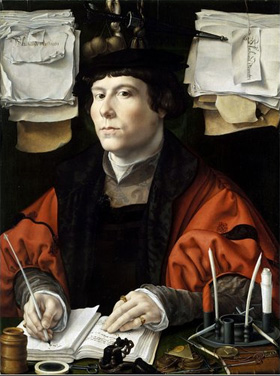

Gossart has no qualms about pleasing his patrons. He designs stained glass and architecture, although the latter never came to completion. He increasingly specializes in portraiture that, like Hans Holbein in Tudor England or Hans Memling before him, gives his sitters both rich clothing and a proper reserve. An old couple may seem less flattering, but only because their portrait approaches genre painting. Bankers, clerics, and a princess tend to wide, piercing eyes and prominent hands, but less and less revealing psychology. Rather, they become actors in an aristocratic theater.

Mannerism as a shifting challenge

Only a few years before, Gossart had brought alive a cleric's fiery intelligence. Perhaps he had to let his guard down that once, for the two panels are most likely a testimony to loss—in memory of the sitter's wife. The skull on the reverse has a startling realism, as well as a startlingly dislocated jaw. Perhaps, too, the artist's change in manner in the 1520s reflects his growing comfort and confidence. He subordinates line more easily to space and shadow. He is in his last decade and a decided success.

With each stage in his life, he touches on another side of Mannerism, from artifice to emotion and back. The late Renaissance is a strange aside in history, even now. One might walk past Gossart in a museum, looking for a more familiar kind of greatness. I had to notice how much less crowded the show becomes after its first room or two. No doubt people coming for a blockbuster find something less welcoming. Even a historian might head straight for the single loan of a van Eyck.

Gossart is more challenging than great, and the pleasure is in the challenge. And the challenge is very much in how he put history through its paces. Even when he copies van Eyck's Madonna in a Cathedral, he bulks her up. He has a recognizable style throughout, with a cool still derived from Antwerp. Yet he has many versions of that style, just as celebrity artists today insist on finding new tricks. His version of art definitely does not run in straight lines.

It cannot possibly, because the whole story line comes from another country, Italy—where early critics saw a falloff after Michelangelo and Raphael. Never mind that both in their last years pretty much typified Mannerism. Over time, historians came to see Agnolo Bronzino, Jacopo da Pontormo, Parmigianino, and others as true originals with strong emotions. Tintoretto and Veronese in Venice had light, color, and the pageant of humanity on display as well. Their reflection on the Renaissance, at times akin to parody, in fact helped create that display. El Greco, who passed through Italy, more or less fits that narrative, but what of the north?

Sometimes it works, as with the archness of the Antwerp Mannerists. Yet Hieronymus Bosch and Matthias Grünewald both overlapped the High Renaissance in Italy, and both were capable of symmetrical compositions, intimacy, and grandeur. And one remembers them both as bordering on despair. Meanwhile Pieter Bruegel, the textbook northern Mannerist, looks at fate, the cycles of nature, or a wedding dance with the utmost serenity. Gossart's most "mannered" composition, a Descent from the Cross that spins a figure eight into contortions akin to Hendrick Goltzius, is most likely not his after all, but rather a follower's. He dislikes exaggeration almost as much as he dislikes any distraction from his work.

Gossart is not one to upset the status quo, no more than a great contemporary, Hans Holbein. He went to Italy as part of a diplomatic mission, rather than a personal one. Humanism is all well and good, but Joseph, the more worldly father, appears just once more with Mary and Jesus—and then behind a ledge and a bit of a buffoon. Art matters, however, and Saint Luke as a painter appears twice. Think of this as a lesson in how to pay close attention to confusing times. Dare I say, much like now.

"Man, Myth, and Sensual Pleasures: Jan Gossart's Renaissance" ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through January 17, 2011.