A Life of Its Own

John Haberin New York City

Aneta Grzeszykowska and Patti Hill

Everyone has those embarrassing moments when the body takes on a life of its own. For a man, they may come in the pain of aging joints or the inexplicable rising between his legs in the middle of the night. For Aneta Grzeszykowska, the uprising verges on mental as well as physical abuse.

And then she gets help from her daughter. Can a photographer who cannot get her own limbs to behave find love? The collaboration seems heartfelt and willing, but it is still treacherous to behold. So are the most ordinary objects for Patti Hill.  If Grzeszykowska builds on Surrealism, Hill encountered the real thing. Yet she took it and photography into an age of photograms and photocopies, with only the ghosts of fine fabrics and train cars.

If Grzeszykowska builds on Surrealism, Hill encountered the real thing. Yet she took it and photography into an age of photograms and photocopies, with only the ghosts of fine fabrics and train cars.

No/body home

Aneta Grzeszykowska takes the body apart, only to find its parts turning on themselves. In her latest work, the turning manifests itself only slowly, which makes it more shocking still. A 2016 video, though, makes clear what has been going on all along. There her four limbs, separated from each other, take her face out of hiding, assault it from all sides, lead it on, and then punish it again. Their torments continue in photographs, where again the odd body parts refuse to add up. This is not all in her head.

Or is it? Grzeszykowska created that video, head and hands together, to reclaim her mind and body as her own, from what a French theorist might call "the abject." In bringing her head and her feelings out in the open, it also serves as a revelation—and the ritual continues in a second video, where sparks fly from her mouth. She becomes her own creation in the photos in another way as well. What looks like her amounts to a paper doll in progress, but molded in parchment and pigskin from her flesh. It is also, often as not, a mask.

It is, she asserts, the body in "No/Body," a two-gallery exhibition. The other gallery contains the defiant no. There she blackens her entire body on video, except for her lips, tits, and crotch. And then she recovers it again in photographic negatives that turn her ghostly presence into white. Nude black and white sculptures, nearly life size, further challenge which version came first. One looks more self-contained, the other more vulnerable, but both could have stepped right out of the negatives and fallen to the floor.

For a woman, who commands her body is a feminist question. And the act of reclamation targets the viewer, not least when male. Grzeszykowska links her work to Cindy Sherman, Ana Mendieta, and a fellow Polish artist, Alina Szapocznikow—and she could well have mentioned Laurie Simmons playing with dolls or Barbara Probst. She inserts her torso in photographs by another, too, much as Sherman places herself in film noir. She has roots in Surrealism as well, as in the choreography of naked and prosthetic limbs for Hans Bellmer or Pierre Molinier. There, too, heads get lost.

Surrealism or domestic habits may account for still another alter ego, a black cat. One contented feline overlooks her naked body stretched out on a sofa, in one of the borrowed photos. Another sculpture, this time in leather, makes her into a cat woman, with pointy ears to show for it. And Grzeszykowska is at her most domestic at her most surreal, in the negatives. They show her with family and at leisure, at home and at the beach. Even there she is applying makeup.

They have their own threats to her body as well. Knee deep in a turbulent black ocean, beneath a black sky, she looks anything but secure. At home, she shares space with what might be children or dolls stiff on the ground. She is still searching in the mirror for her reflection and herself. Yet she shows no sign of terror. No/body is at home.

Not waving but drowning

A girl and her mother lie on their backs together, basking in shallow water. Their heads point in opposite directions, almost nestling in one another's shoulders. They invite one to join in a moment of intimacy and an afternoon at the lake, only the water is too weedy and murky to provide true solace, and it may be drawing them down. The girl has shut her eyes and opened her mouth, in pleasure or in danger, and what I took for her mother is lifeless and unaware. They could, as in the poem, be "much farther out that you thought / And not waving but drowning." Like the staged photograph, they are also not communing with nature, but questioning the natural.

With her last show, Grzeszykowska was literally setting off fireworks. They emerged on video from her mouth, along with much else, and her limbs more often than not lay apart from her, refusing to behave. They spoke to pride at being a woman and making art as a woman, but also the cost. Did she, in retrospect, shout too loudly and focus too much like Marilyn Minter on her abjection and herself? If so, her 2018 photographs have found a collaborator in her daughter and grown closer to silence, even with that open mouth. And her daughter in turn has found a playmate in a mere image of her mother, a life-size mannequin with neither arms nor legs.

That series, Mama, is all about psychic and body doubles, with the usual creepy overtones after Surrealism, Sigmund Freud, and his modern or postmodern followers. It brings her closer than ever to Sherman—not this time to Sherman's Untitled Film Stills, but to her later work, lying abjectly and ostentatiously in rotting leaves like Grzeszykowska and her daughter in the weeds. It also makes explicit the debt to others who play with dismemberment and dolls, like Simmons and Bellmer. Photos of her child may bring her closer as well to Sally Mann, but with an artist from Poland rather than the rural South. Smeared all over with lipstick, the mannequin even resembles Mann's son with a seriously bloody nose. One just has to accept that both kids are just playing around.

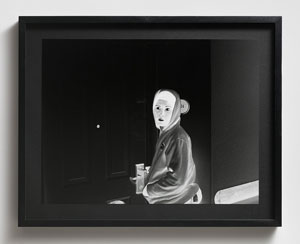

A second new series speaks more quietly than before, too. It even enforces silence. Here Grzeszykowska seeks solace not in mothering, but in a fashion accessory meant to revitalize a woman's skin, a beauty mask. And here, too, the promise of creature comforts cuts both ways. A mask, like fashion itself, can offer protection or a place to hide—and one mask does look like equipment for ice hockey or a prop in a slasher movie. Masks can also constrain and confine, and softer beauty masks fit tightly, with limited gaps for sullen eyes and mouth.

Those, too, could serve for play or as accessories to a crime, like a ski mask for a terrorist. And with both new series, play can have sinister overtones. The girl, I want to say, is "just playing with her mother," and the photographer is "just playing with her little girl." That can mean playing together or one manipulating the other—exactly what makes Mann so unsettling for many. Meanwhile Mann's children think of themselves as not willfully exposed, but rather taking on a role, and so no doubt does Grzeszykowska's daughter. She gets to apply the lipstick, in purple and red, like a girl's first attempt at smearing on war paint or blood.

The show opens with the Body Masks, but it darkens with Mama without altogether losing its sense of intimacy and joy. When she takes the legless creature to the lake's shore in a wheelbarrow, she could be sharing a special moment with her mother or about to dispose of the body. The mannequin seems older than the woman herself, with paler hair and icy skin, but also more caring and knowing. The girl seems to appreciate that when she leans her head against its shoulder, eyes closed, or stands behind it with her hands over its eyes. What could be a more innocent game, if also a guessing game, even if I took it at first for Grzeszykowska's contorting herself? Only when she grows up will the child know that she, like Stevie Smith, "was too far out all her life / And not waving but drowning."

Weekends at the office

If I did not know better, I would take Patti Hill for a fiction. But then she moved so easily between fact and fiction in her writings that one hardly knows which to call fiction or memoir. She did much the same in her pictures, but with an added twist: for her, both art and life her were a source of found objects. And then she used them both for photocopies. It makes her no less a creative artist, but it allows her to hold everyday objects, images, and herself at more than one remove from the familiar.

Actually, I do not know better, at least not on my own, but I do trust her gallery and its press release. (They have a job to do after all.) Hill is the second woman with roots in early modern art new to me in just a week or two, along with Hilma af Klint and the likely birth of abstract painting at the Guggenheim. Her art is less original, because that is its very theme and its medium, but her life all the more remarkable for that. Born in Kentucky, she may sound like a regional artist and a real American (whatever that is), but she divided her time between Connecticut, New York, and Europe. Born in 1921, she may seem to belong to another era, but she lived until 2014—long enough to make art as if she had a job to do this very day at the office.

Actually, I do not know better, at least not on my own, but I do trust her gallery and its press release. (They have a job to do after all.) Hill is the second woman with roots in early modern art new to me in just a week or two, along with Hilma af Klint and the likely birth of abstract painting at the Guggenheim. Her art is less original, because that is its very theme and its medium, but her life all the more remarkable for that. Born in Kentucky, she may sound like a regional artist and a real American (whatever that is), but she divided her time between Connecticut, New York, and Europe. Born in 1921, she may seem to belong to another era, but she lived until 2014—long enough to make art as if she had a job to do this very day at the office.

She modeled for magazine covers and wrote for Seventeen and Mademoiselle, but also for The Paris Review and herself. She published poetry, the kind that runs to fragments and aphorisms, and her books interweave it with her photocopies. The poetry and the copies alike become a kind of text art. She gained access to IBM on weekends for its copy machines—surely relishing the irony that copying back then was supposed a woman's job, for secretaries, and that weekends were a time for play. In time Charles Eames, the designer and architect, convinced IBM to loan her a machine to call her own. It testifies to her many lives that she met him on a flight to New York from Paris.

She may have encountered photograms by Man Ray in Paris or New York, at MoMA, and she must recognized something of herself. Recently photocopy art at the Whitney took up his legacy, and here, too, art has a ghostly glow—all the more so because Hill worked almost exclusively in black and white. One work lends its title to the show, How Something Can Have Been at One Time and in One Place and Nowhere Else Ever Again, and everything in it comes with that implicit question mark. She sees ghosts everywhere, including the ghosts of art. She began with copies of reproductions of the history of photography (oh, so many removes), along with copies of press archives, in which people are at risk every day. And the aura of death extends to a 1978 suite of copies of a swan that had washed up on the beach, from its full feathered body to its skeleton and its heart.

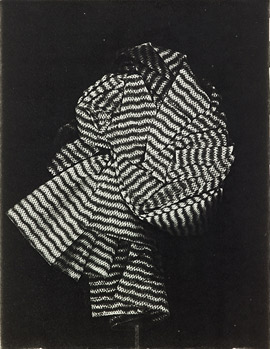

I would love to see those series, along with copies from the 1980s of the palace of Versailles. I would also love to know how in the world she subjected it, from plush surfaces to paving stones, to a copy machine's glass plate. The works on view are strange enough all by themselves—including fifteen images from 1983 of a single scarf. Hill folds and refolds it as if making sculpture, and its silk takes on the thickness of stone or wool. Earlier images of clothing, from 1976, allow one to imagine their absent wearers as ghosts. In between come elusive objects that announce by now their place in the past, like a sardine tin, a dead fish, or a rose paired with a comb.

One last set, The Golden Arrow, brings the interior of a railway car to the electrostatic plate. It lingers on narrow passages as vistas onto bygone luxury. Hill here copied advertisements, in which even the tiny bathrooms gleam. But then she always challenges one to say what is a fiction and what she held in her hand. Coming after the other garments to a freshly laundered shirt (with a label that says just that), I could hardly know myself. Instead of art's holding a mirror up to nature, she holds art and nature itself to a glass.

Aneta Grzeszykowska ran at 11R and Lyles & King through October 16, 2016, and at Lyles & King through November 18, 2018, Patti Hill at Essex Street through October 21, 2018.