The Natural

John Haberin New York City

Ana Mendieta and Phoebe Washburn

Pablo Picasso famously claimed that, as a young man, he could draw like an Old Master, but it took him a lifetime to paint like a child. But could a child paint like him—even a girl?

Picasso's one-liner, like his drawn lines, suggests Modernism's messy rediscovery of art and nature. On the one hand, a return to childhood can stand for making the visible unfamiliar, as only an artist can. On the other hand, it promises to recapture a higher kind of nature, in the art object and the subject of his art. As so often with Picasso, the first half, the artist, is the male, the desirer, the master of a lifetime at work. The second, the subject, has a way of being the woman, the desired, the youth.

In effect, art dances around three old associations with nature—unspoiled, feminine, and inspiring. It leaves an artist in control, and yet it leaves its imprint like a force of nature. For a young female artist, that offers plenty of temptations and plenty of opportunities to upset the equation. Take the strange ecology of Ana Mendieta, Phoebe Washburn, and, first, yes, an actual little girl. In different ways, they suggest that the apparent simplicity of nature exists only in the traces of art. A postscript follows memories of Mendieta to 2008, in her encounters with Hans Breder.

What do they know?

Did Pablo Picasso—or a more obvious force of nature like Jackson Pollock—really paint like a child? Apparently, enough people think so. An article in the Times this fall relished the story of a four-year-old girl. Her paintings may not be selling like Picasso or Jackson Pollock, but at least they are selling. That would make her more mature than most artists. But is it enough?

Picasso's lean line has far less resemblance to the Old Masters, particularly J. A. D. Ingres, than he liked to believe. And I wonder how willingly he spent time with those of the opposite sex under the legal age. That said, one can learn a lot from a little girl—and not about the innocent eye.

I do not mean just learning her art, which seems perfectly appealing in the thumbnail view of a newspaper and its Web site. One might mistake it for the work of an Abstract Expressionist who had a sudden, inexplicable infusion of insane optimism—or perhaps reverted to four years old. It has just enough loose line, just enough symmetry, just enough bright color, and just enough hint of plain old drawing to pass for creature comforts. It has just enough irony simply in coming from a child to pass for Postmodernism, like the Asian elephant footprints exhibited as abstract art by Komar and Melamid this same year. No, I mean that Picasso could have learned, if one can imagine it, even more confidence in his art.

People still like to think of western realism as something that comes naturally, without learning. But kids today do not draw like Ingres. They may prefer finger-painting or crayons, but either way, they draw what they know. Picasso did, too, when he emulated Ingres, and so did Ingres, when he simulated in pen a silverpoint technique that had become archaic by the late Renaissance. However, these days children and their teachers know television—or abstraction—better than they know Ingres and Picasso.

That suggests the need for history, for time alone with art, and maybe even for people like you and me. As Groucho Marx said, "Why, a three-year-old child could understand this. Run out and get me a three-year-old child." If he wanted media attention, he was off by just a year.

Even more, it serves as a reminder that every component of the picture takes understanding. I include representation, symbolism, language, abstraction, and even a sense of play. So consider the work of two young but very grown-up women artists. One buys into a "natural" sense of art or of femininity. The other tears them both to shreds.

Mother earth

The Whitney called its retrospective of Ana Mendieta "Earth Body: 1972–1985," summing up a short career and an abbreviated life. The museum had all it could do to fill out a retrospective with every record of her work. It often looked forced and repetitive, but it had the virtue of its insistent focus. Mendieta built her work around her own body, like Francesca Woodman, and she insistently identified her body with her gender—and her gender with the earth.

One remembers her arm prints on canvas, like yet another a child playing with finger paint or fascinated at seeing her hand print on glass. One remembers, too, the surrounding white space, as she let the full length of her body drag down the canvas. One feels herself and the work drawn by something outside both and more than one woman could ever control. One remembers that two other poles of her work are Havana, her birthplace, and the New York scene, in an era of plain imagery and performance, of the American landscape as digital terror, of the scrap heap of Richard Serra or the violence and "erotic rituals" of Marina Abramovic, Aneta Grzeszykowska, and Ulay.

Soon Mendieta leaves the canvas behind, and the covering of red liquid becomes more literally an extension of her and nature. She dresses her naked self in blood and chicken feathers. She had been taking her roots more seriously since visits to Cuba, but the blood is definitely not that of politics, whether Castro's or imperialism. She has in mind older rituals, not to mention the continued sacrifices inherent in sustenance and death. Dirt itself becomes her third trademark, in large photographs of her imprint on the ground, shaped to evoke female genitals. They feel the loveliest and most crafted, because of the large-scale color and the texture of her impression, but also because the paradox of her self-creation works best when she's not there.

Mendieta has become an icon in her own right, of a woman's art, a woman's history, and ethnic diversity in an unreceptive time. Many know her as nothing more than a footnote to Minimalism, as in a show of "Transmissions," remote from a contemporary Cuban artist like Yoan Capote, Juan Francisco Elso, or Belkis Ayón. Carl Andre was accused of murder after her death at age 36, in a fall from a window. I will think of her more for yet another pole of her art, upsetting the urgency of nature more than her admirers or she herself would recognize—the trace of her ego confronting the world. Fictive landscapes like that of Christina McPhee would make no sense without her.

I mean how much every work is about her mark, as if anticipating that her memory will flourish most in her absence. I mean how carefully she puts that mark on everything. People do not naturally dress up like chickens, except in ad campaigns and halftime shows. The earth did not swallow her up, leaving a shallow impression: she put it there. Even that image of her genitals is outsize. A mere viewer can admire the photographs or the marks on earth, but, unlike in a work by Andre, no one could to touch either one without spoiling it.

"Difference feminism" may sound natural, but other women—Lee Bontecou, Eva Hesse, Agnes Martin—left their mark on the materials and forms of Minimalism in very much other ways. Earth, nature, process, and eternity sounds natural, too, but also pretentious, and that is perhaps the lasting point: she never leaves the stage, even when one cannot see her. She may comes off as about as shallow as that impression. She may come off as silly as a plucked chicken trying to regain its feathers. Yet she sustains the paradoxes long enough to deserve some attention for what her insistence could not say.

The living end

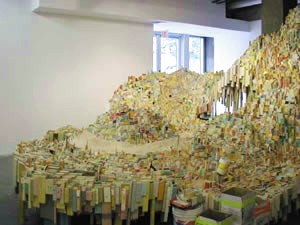

Phoebe Washburn is ready to say anything, and she is ready, too, to pick up the tools of a traditionally male carpenter's shop to say it. She fills a gallery to the limits and dares the viewer to find how to take it in. At P.S. 1 this very summer, her recycling of scraps allowed a work to grow to the point of sculpture but also dysfunction. Cardboard all but spilled out of the basement room and barred entry, and I worried that it also barred a serious encounter. It seemed to take on a static bulk and to assert an artist's ego, with not quite enough self-mockery or structural complexity to avoid echoing Dieter Roth and his posturing upstairs.

And I was wrong, because I, too, contributed to barring my experience. Still, if an artist can have learned something in a month, perhaps Washburn did along with me. The newer piece preserves the earlier one's self-reflective evolution while opening up and letting the chaos and the metaphors tumble out. She has an open-endedness that makes a trash collector as similar as Charlotte Becket seem downright high modernist. When she shows even more self-restraint, back at P.S. 1 for "Greater New York 2005" or inside and out at SculptureCenter for "Make It Now," things will never be the same.

Visually, the work emerges from the basement and reaches for a sky of its own making. Experientially, it requires visitors to work their way out of its confines and to discover a way to hold it all before their eyes. It makes one recreate the piece's temporal dynamics in one's path through the gallery. And it makes Modernism's ideals of nature and the sublime, of the utopian city, and of the nature of art wrestle big time. Lest one is looking for another mother figure or delicate young woman here, Washburn calls it Nothing's Cutie, but it has a life of its own.

Like Sarah Sze, she refuses to let go of anything, while making that fact her subject. If tape directs where a supporting strut will stand, the tape stays, and I bet she is not above inserting a few more arrows for good measure. If a box brings the deep-black screws that hold the untold number of wooden scraps together, that, too, enters the work, along with the sawdust that falls in the process. The wooden slats could make a crate for shipping art, but they carry only the concept—and themselves.

However much the work resembles process art of the 1960s or the controlling impulse of a Living Unit by Andrea Zittel, it is too savvy and way too funny for an appeal to raw earth. It definitely does not sit still to take the gallery or the artist's studio as its muse. To take it in, one passes beneath the confining scaffolding, emerges into the main space, and discovers a fictive city. The wood defines its towers, the sawdust its parks and beaches. She never stops shaping an experience that runs to disorder. Toward the window, in a plastic container now holding still more debris, some leftover Phillips-head screws in the dust spell out The End.

And indeed, there is nothing left but to retrace one's steps to the exit. Could the construct offer a model for the future, of a humanity that recycles its detritus, or does it mock that concept, along with Earthworks or any such appeal to entropy and eternity? Does it supply a warning of what happens when all the garbage piles too high, like Chelsea, for that matter? Does it offer a postmodern version of Thomas Cole and his Course of Empire or Charles Baudelaire's "unreal city," now that dreams of imperialism and Modernism threaten to dissolve in a less than comforting chaos? It almost begs to take on metaphors and profundity, but I admire even more its distrust of them. Just as long as you and nature follow the tape arrows on your way out.

Chicken out

When the Whitney called its 2004 retrospective of Mendieta "Earth Body," it dared one to separate the chain of nouns without a verb. It identified her art with the artist, the artist with her body, and her body with the earth. A photograph or a painting served as a record of a performance, the artist's imprint on paper or canvas. Her performance clothed only in chicken feathers and blood left the imprint of art and nature on her.

One might also, however, see earth and body as diverging poles of her art. Mendieta then exists only either in isolation, as a naked body and a struggling woman artist, or in community with the entire planet. Galerie Lelong proposes something less singular—a collaboration with Hans Breder. Where her short life took her from Cuba to New York, with too little time in either one, the show focuses on her stop in between, in the Intermedia Program at the University of Iowa. Where the Whitney defined her art in terms of personal identity, as a woman, this show identifies her with her lover and teacher. Where the museum offered nouns, it supplies only a verb, "Converge."

Breder's photographs contributed to her 2004 retrospective. The gallery makes even more use of them, as well as of her image. It intersperses their photographs and video, with hardly a painting in sight. Mendieta gets to hold a chicken, although without tearing off its feathers. Otherwise, the show comes across as a rush of naked bodies on the beach, often faceless and intertwined. Without the list of works, one might not know which artist is which.

Actually, the list attributes each work to a single artist, and they get easier and easier to tell apart. The careful assemblages of legs and bottoms belong to Breder. Mendieta stands alone, give or take the chicken, as if unsure what to do with herself. His bodies glisten and approach abstraction. Hers remains awkward and real. Menstrual or chicken blood might flow at any moment.

Breder, like Barbara Probst, is making obscure objects of desire. Mendieta is making almost a single, extended performance, although one that seems barely premeditated and in need of a plot. In other words, he is making lives into art, and she is identifying art with her whole life. He looks back to Modernism, while she belongs fully to art after the 1960s. He also falls between two rawer and nastier times in art, Surrealism and the present. His piled bodies resemble those of Hans Bellmer, but without his implied threats of dismemberment and sex.

The presentation obviously hides a great deal. It gives the lesser-known artist an edge, in both senses, while giving Mendieta a little more polish than usual. It also mutes or qualifies her feminism. These days, a celebrated artist's love affair with a student could open him to a lawsuit—and maybe some tabloid headings. Still, the gallery draws attention to his work and influence better than have solo shows in the past. In turn it fills out her career and identity, as neither victim nor a supposed female essence.

"Ana Mendieta: Earth Body" ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through September 19, 2004, Phoebe Washburn's "Nothing's Cutie" at LFL through October 2. Mendieta's encounters with Hans Breda ran at Galerie Lelong through March 1, 2008.