Unvarnished Impressionism

John Haberin New York City

Edouard Manet: Woman in a Striped Dress

Obsession: Klimt, Schiele, and Picasso

When layers of aging varnish come off a much-debated painting, one can expect a greater clarity. One might even hope for a revelation. The Guggenheim sure delivers on the latter, with Edouard Manet.

Woman in a Striped Dress has returned to the museum's Thannhauser collection, after three years of research and conservation. It has an unanticipated brilliance, in its brighter, lighter, and deeper colors.  It becomes a study in fashion and art alike, with that striped dress and the greater approach to Impressionism of Manet's late years. It becomes, too, a study in character, with a woman who holds her own amid the slashing brushwork. As for clarity, a complex artist provides anything but—only starting with the color of her dress. As a postscript, the Scofield Thayer collection of the Met picks up portrayals of women and the origins of Modernism.

It becomes a study in fashion and art alike, with that striped dress and the greater approach to Impressionism of Manet's late years. It becomes, too, a study in character, with a woman who holds her own amid the slashing brushwork. As for clarity, a complex artist provides anything but—only starting with the color of her dress. As a postscript, the Scofield Thayer collection of the Met picks up portrayals of women and the origins of Modernism.

Taking Manet for granted

One does not often celebrate a museum's highlights leaving town. The Justin K. Thannhauser Collection entered the Guggenheim in stages, starting with a gift in 1965, and it has never once left, till now. Nearly fifty of its seventy-odd works headed off for a year, with stops at the Guggenheim Bilbao and in Provence. The show has, though, provided the occasion for a fresh look at how the works should appear. It became plain that this women badly needed attention, and the museum singled the painting out for cleaning. If you missed its unveiling, it returned in September 2019.

Some will celebrate the painting's departure, I fear, for a different reason. One might well take it for granted, like the Guggenheim's entire permanent collection. One passes the wing on the way to massive exhibitions, like that of Alberto Giacometti, or to contemporary art in the tower galleries, like the Asian art in "One Hand Clapping." It has its workhorses in a large village scene by Camille Pissarro and the early Woman Ironing by Pablo Picasso. It has its share of still life by Paul Cézanne and figures absorbed in their work and the land by Georges Seurat. Still, it all but dances around the glory years of Impressionism and the rigor of Cubism, despite two dense paintings by Georges Braque, on the way to Picasso in the 1930s.

The painting could use, then, some fresh attention. It long hung beside his woman at a dressing mirror, suffering in comparison to her dizzying and doubling. That woman appears from behind—and then in a glimpse in the mirror from the front and in echoes of her white and blue on the wall behind. The woman in a striped dress, in contrast, simply faces front, and her face is almost blank apart from dark eyes, a raised eyebrow, and a peculiar red spot below her red lips. Historians have connected her to the title character in Nana by Emile Zola, a courtesan, but the painting is not designed to shock. It is meant to shine.

One will never see Woman in a Striped Dress (later a subject for Edouard Vuillard as well) as it was for Manet. It looks intact in a fancy frame, but it was cut down after his death, to hone in on the figure. Maybe her relationship to the background was once dizzying, too. One can, though, see her now without yellowed varnish and some added paint. An unknown hand touched it up to clarify matters. Be grateful that no one has corrected Claude Monet at Giverny for his failing eyesight.

Every conservation effort runs the opposite risk, of over-cleaning, but the Guggenheim took its time. Gillian McMillan led the restoration, drawing on the Met's conservators as well as the Guggenheim's. And Vivien Greene led the investigation into not just the painting's condition, but also its subject, to pin down what to do. The team looked at even wallpaper patterns of the time. "We try," Greene says, "to get to the truth of things, literally and conceptually." With Manet, though, truth is always an open question.

Maybe it always is. Jacques Derrida called an essay on that same period "The Truth in Painting." His critical theory has lost ground to others (speaking of fashion), but Manet would have enjoyed the implicit scare quotes. Who, for starters, is the woman? Was she as fashionable as her tight corset and as elegant as her long, dark gloves? Was she an actress (perhaps Suzanne Reichenberg), a professional model, or a whore? Manet died at fifty-one from complications from syphilis, in 1883, as little as three years after completing the painting.

Back in fashion

The Guggenheim is not saying, but then it has to throw up its hands at the background, too. Is it a trellis, one that Manet kept in his garden for painting outdoors? Is it wallpaper after all—or a decorative painted wall? Strong lighting suggests a real garden, but the woman stands beside a fancy side table from his studio. One looks in vain, too, for a path into the landscape. This woman is not going anywhere fast.

Either way, the background is indeed dizzying, and so now is the woman. Unlike her, Manet has his gloves off. Front lighting dissolves a patch of stripes into white, while others run in quite another direction from folds in her dress. Thanks his brush, they become all but crosshatching. Much the same flurry fills the background, only more tightly and in contrasting reds, yellow, and greens. It extends, too, to the fan in her left hand.

Foreground and background come together in the profusion, along with reality and art. The background could be wallpaper, but even then it may hold a few leaves. The Louis XV table holds a basket of fruit. The fan may have a floral pattern as well, after French fashion or Japanese art. Where is the woman in all this, between nature and culture? That question may lie at the painting's heart.

The very question challenges high society and sexism—much like the nude's demand for eye contact in Manet's Olympia, which horrified the Paris Salon in 1865, or the mix of nude and clothed figures in Le Déjeuner sur l'Herbe two years before. The woman's face is a place of rest amid the flurry, to the point that one can count the brushstrokes. Is that because the artist cared less for her than for her dress, or does it lend her a greater dignity? Colors lighten just above and behind her raised hair, like a halo. Her brightness also thrusts her forward into the space of the viewer, where one can just make out the flesh beneath her sleeves. She is not quite life size, but the painting is.

Conservation makes the challenge visible as never before. I had taken the varnishing for granted, too, because it left the stripes black and the background close to green. And what artist then did more with black and acid color than Edouard Manet, as in Manet's portrait of his wife, until Pierre-Auguste Renoir resisted his love of pink long enough to paint La Loge? Now, though, Manet's approach to Impressionism is inescapable. The black has become a deep blue or violet gray in a dazzling field of white. The sole remaining dark patch, under the side table, could outline a monster.

Manet's brush dominates more than ever. It all but scrapes against the canvas, much like another favored medium, pastel. (The Guggenheim hangs a portrait sketch of a countess, in pastel on canvas, immediately to the left.) If conservation is an undoing, he got there first. His earlier interests run as far astray as Spanish painting and the American Civil War. Here he came back in fashion.

Classicism and sex

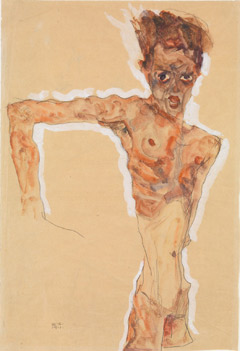

When the Met Breuer promises nudes by Klimt, Schiele, and Picasso, it might come as a tease—a delight or a disappointment, depending on how one approaches sex. The trio of names, as tantalizing as the word nudes, ends on a slightly jarring note at that. Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele exemplify an Austrian art of patterning and expressionism, its lush color and raw flesh haunted by death, even in a Schiele self-portrait. Picasso, in turn, exemplifies optimism and experiment, setting aside his Blue Period to reinvent himself again and again, along with art. Schiele learned from Klimt, his elder by nearly eighteen years, while Pablo Picasso pretty much ignored them both. Throw in the course from Dada to Surrealism, and one has the distinct paths of modern art.

Yet Scofield Thayer collected all three, and he saw them as united by eroticism and, the Met argues (in context of Picasso), an "unselfconscious classicism." Born in 1889, the year before Schiele, he could count himself among them as well. He founded and edited The Dial, which nurtured Modernism in prose, and he befriended Paul Rosenberg, the dealer who promoted it in art. He left his collection to the Met, which now displays a selection as "Obsession." A mere fifty works on paper hardly counts as a blockbuster, but the museum plainly hopes for one in whittling six hundred objects down to those three names. The title may sound like a cologne, but it embraces their slightly cloying aroma, too. This is, after all, about sex and death.

Yet Scofield Thayer collected all three, and he saw them as united by eroticism and, the Met argues (in context of Picasso), an "unselfconscious classicism." Born in 1889, the year before Schiele, he could count himself among them as well. He founded and edited The Dial, which nurtured Modernism in prose, and he befriended Paul Rosenberg, the dealer who promoted it in art. He left his collection to the Met, which now displays a selection as "Obsession." A mere fifty works on paper hardly counts as a blockbuster, but the museum plainly hopes for one in whittling six hundred objects down to those three names. The title may sound like a cologne, but it embraces their slightly cloying aroma, too. This is, after all, about sex and death.

It has been a long time coming. One has to distrust yet another tribute to a collector, even for Robert Lehman at the museum last year, but this donor is safely beyond flattery. His promised gift of 1925 came, as he intended, only after his death in 1982—and even then without a welcoming exhibition. Says the curator, Sabine Rewald, the Met hardly knew how to approach its size and diversity. Even now, it makes no effort to describe what it omits, and its choices (by no means all nudes) have to be suspect. That, though, may be the most valuable part of the tease.

Classicism? That hardly characterizes Cubism, but Thayer distrusted it along with abstraction, and a room for Picasso skips right over it—from summer in Catalonia with Fernande Olivier in 2006 to the Neoclassicism of the early 1920s. The term seems less appropriate still for what the Nazis denounced as degenerate art, but look what happens when its lush color falls away. Even when he adds touches of watercolor and gouache, Klimt's spare outlines approach Picasso's, and his faces approach masks. A flurry of pencil for fabric gives the only hint of his decorative flatness—while small reproductions of finished paintings on museum walls only drive home how much the drawings leave out. Schiele starts similarly, and his late nudes take on firmer outlines still in charcoal.

Sex? That goes without saying for Klimt, who accented public hair even when he did not sketch women masturbating. As for Schiele portraits, even a mother and daughter are caught in an erotic embrace. He got in trouble for "public immorality," harboring if not necessarily abducting his underage models, but he found others in the children of adults who posed for him as well. Even Lewis Carroll might be appalled. Picasso again takes selectivity, but he did portray a brothel in 1903, as La Douleur, with the woman prostrate before her bored client—and then, of course, comes the greater challenge of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. The show ends before late Picasso, with more of his wives and mistresses, but then the collector never got to them.

Like many a tease, Thayer's bang ended in a whimper. He collected at an astounding pace in just a two-year span, starting in 1921, and he ended his days in near isolation in Martha's Vineyard. Still, his collection points to ambiguities in more familiar works as well. Are Klimt's seemingly floating nudes posing or resting between moments of artifice? Are Schiele's observations clinical or wildly distorted? A gaunt self-portrait with blotchy flesh has him already dying seven years before the fact, but flaring hair, gaping eyes, and an extended arm keep him perilously alive.

Edouard Manet recovered his place at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum on June 19, 2018, and the Scofield Thayer collection ran at Met Breuer through October 7. The Thannhauser collection went on tour from September 21, 2018, through September 22, 2019.