1.8.24 — His Own Private Hell

Max Beckmann returned from World War I in his thirties, a mature artist and a broken man. His service as a medical orderly had ended prematurely, in metal and physical collapse, but his success had only just begun.

He found a ready market for his portraits in the freedom and sophistication of Weimar Germany. He found a subject, too, in the degradations he had witnessed and could not escape now.  The Neue Galerie sees just eight years as a key to his more iconic later work. His mythic narratives arose, it argues, from the pleasures and poverty before his eyes.

The Neue Galerie sees just eight years as a key to his more iconic later work. His mythic narratives arose, it argues, from the pleasures and poverty before his eyes.

New York got a good look at Beckmann in 2003, on what was just his most recent museum retrospective. One could call it political art, I wrote then, but his allegories never quite reveal their key. One could call it German Expressionism, but he himself would not, and his images rarely give up their sober colors, solid outlines, and mythic past. One could almost call it Modernism, but the tortured narratives, thick bodies, and grim faces scorn such experiments as well. A more recent exhibition took Beckmann into exile soon before his death. With your indulgence, I leave a fuller account to my reviews at the time, with more on his style, images, and career.

The Neue Galerie, in turn, offers not a survey, but a substantial correction, through January 15. It gives space to prints and drawings, at least half the show’s one hundred works. That is not a failing, because they were a big part of his output. Subjects could sit for them quickly and gain less costly access to his allegories, almost like the public for graphic novels today. And Beckmann responded to demand with large prints. He also, it turns out, was not just darkening his line with the medievalism of woodcuts. At least as often, he took to drypoint for quick, light hatching—finding echoes in the shocking skin tones of his paintings.

He could not let go of crushing memories. He sketches a morgue, a hospital, and open latrines. Nor could he stop looking. Cripples and beggars lay splayed or hunched on the street. Prints show the rising class that he deplored and with which he identified—those who sat for his portraits and attended the same supper clubs and carnivals. From past shows, you may know his early bathers after Paul Cézanne or later Vikings on a voyage of conquest. The wealthy, it turns out, could always rent a boat for the day.

It could not have been easy to enjoy each other’s company. You may remember Beckmann’s subjects as larger than life, himself included. Here, though, they pack the picture plane, with the lowest often upside down. It is only a step from an early Descent from the Cross to a carnival act. They hardly acknowledge one another as well—not even Adam and Eve at the temptation, where their tempter looks less like a serpent than a wolf. Jesus gestures to his followers as if putting them off.

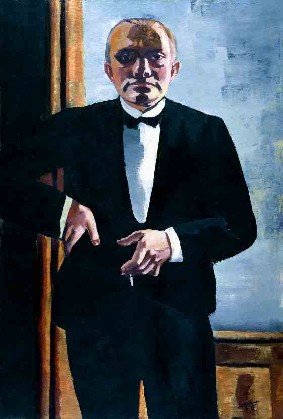

Color comes as a corrective, too, to typical accounts of so dark an artist. It also came with success. One can see why he became the go-to guy for portraits. He does not have to flatter the new leisure class, not when he himself could aspire to a felt intelligence and self-possession. Maybe that is why they need few attributes, but Beckmann needs his tuxedo, cigarette, and horn. Art itself must have lifted him out of a breakdown.

He began teaching at the academy in Frankfurt, in 1925, and exhibited in Mannheim with the Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity. Had he distanced himself from Expressionism or given it a lasting model, and what kind of “objectivity” could comport with his growing interest in theosophy? He still had to face the collapse of the republic. Yet the exhibition comes to an end well before the Nazis came to power, confiscated his art, and sent him packing. By then, it is hard to distinguish his Family Picture from his Dream. He had long since survived boredom, banality, and his own private hell.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.