11.3.25 — Whose Recent History?

Must artists recover the past? Can anyone? Galleries themselves are returning to territory that they were largely giving up when I was just discovering art. Back in the days of fewer and fewer affordable Soho lofts and cutting-edge Soho galleries, Tribeca was already becoming the place to be for an exploding financial and party sector. Do not even ask how those two ever got along. But greed, you may remember, was good—and I work this together with a recent report on Richard van Buren and more of the shift in the gallery scene to Tribeca as a longer review and my latest upload.

I never belonged there, but I did watch uncertainly as the likes of Julian Schnabel and, in different ways, the “Pictures generation” upstaged Modernism. Now artists and dealers are more likely to approach their own past with caution. Hadi Falapishi, for one, seems to have little patience for more than cartoons. He paints faces in acid colors that positively shout cartoons. And yet this is his past, too.

That is because it is also art. He nurtures the sense that each may provide a glimpse of more at Andrew Kreps through November 1. Pairs of them crowd together in paintings that speak of tension—or is it all in fun? Falapishi leaves that possibility open, too, because he seems to prefer that art have fun. You have seen these motifs before, like a sailing ship with a hasty smile on its sail, like a painting or a living thing? This might almost be Postmodernism quoting René Magritte or Magritte quoting Postmodernism. Surrealism it is not.

In other words, it is all about ambivalence and all about the past. (They go together.) He appeared with the gallery in the 2024 art fairs, but now he takes the weight of history such as it is. He calls it “Gut Feelings (Trauma Dumps and Love Bombs).” Be forewarned. I had mixed feelings about its cast of characters, but it prompted me to seek out the past for myself.

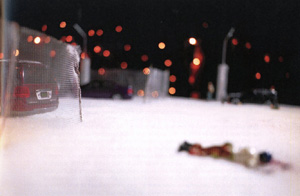

Erin M. Riley looks to her own past, and yet she, too, finds tradition in art. Like Kay Sekimachi, at Falapishi’s gallery, she turns to weaving while calling it a personal memory. She works in loosely woven wool and cotton, at P.P.O.W. through October 18, the clumsier but more ambitious the better. It incorporates images of video looking older and clumsier than it would appear in life. It conveys stories, too, of the girl home alone making it to this point as a woman. As one frankly clumsy painted title has it, You Broke My Heart.

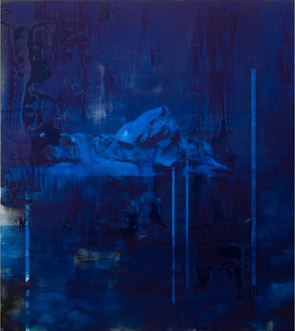

Riley shares her gallery with Elizabeth Glaessner, whose panted alter ego emerges out of a haze, a swamp, or a dream. Riley, though, has even better stories, if you can decipher them. Just try to find all the fragments of her suspended in compressed space. Try to believe from spare white outlines of something uncertain against the deeper colors and approach to darkness of Somebody Cares. She may still feel the fresh tar on a newly paved country road. She may remember her grandfather as someone solid though those who come to him for comfort are question marks. She has no choice but to see a rose and a teddy bear and to believe that they belong to her.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.